This story is published in collaboration with LitHub.

I first came across Stig Dagerman and his books sometime in the first months of 2011, in the foreign language section at Dussmann’s bookstore, on the Friedrichstraße, shortly after moving to Berlin. The city lent itself to long conversations about history and politics, and I read voraciously on subjects I had seldom thought about while trying to understand the country I was living in. I visited Dussmann often and my purchases were aspirational and chaotic. The title German Autumn, with the black and white photo of a bombed-out building on the cover, promised to fill a sliver of my quickly expanding ignorance. I assumed the author was German: Dagerman. He was Swedish, and his reportage through the rubble of 1946 Germany was written with uncompromising clarity and sensitivity that stuck with me.

While still in Berlin I read his novel A Burnt Child, and though I don’t remember why, I finished the last pages while pacing frantically outside the door of our apartment on the Köpenickerstrasse in the middle of the night. I remember that my postscript to that book was a plunge into the internet to learn more about this man, his life, and how he’d come to write like this. I got the usual synopsis, vague or prudent, on his precocity and tragedy, which I would come to know by heart. I stumbled on the name of a daughter and found her on Facebook. There was no mistake possible: one of her most recent posts featured a photo — in black and white, like all photos of him ever taken — with a message on mental health, the consequences of depression, and the help her father never received. Eventually, I wrote to her; she never answered. It was a message of gratitude, the type of zealous letter you write when still full of the voice that accompanied you while reading, still in a daze from the book you’d swear you’re the first to ever discover quite like that.

Over the next years, I’d look for him while perusing books, and even got lucky a couple of times, in the south of France and, of all places, Tucson, Arizona. Over time, I accumulated his works and testimonies the world over that spoke of this literary comet, of greatness interrupted. The enduring power of his story was such that in his 2008 Nobel Prize acceptance speech French writer Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio spoke at length about Dagerman’s role in his own life: “Stig Dagerman’s little sentence is still echoing in my memory, and for this reason I want to read it and re-read it, to fill myself with it. There is a note of despair in his words, and something triumphant at the same time, because it is in bitterness that we can find the grain of truth that each of us seeks. ”

Ultimately I placed him on the vague shelf of themes to delve into and maybe write about one day.

In May 2019 I had been in Washington DC for three months, and the city felt more lonely than any I’d lived in, so I signed up for countless newsletters of embassies and cultural centers that animate the capital, to somehow fill my time. That’s how I read about an event at the Alliance Française called Digging Deep Into the Shadows: film screening & book talk, on Friday, May 10th, featuring a movie based on the play “Marty’s Shadow,” by Stig Dagerman. It would be followed by a Q&A with Lo Dagerman and Nancy Pick, co-authors of The Writer and the Refugee, the book on the story that had inspired the play. I went, stayed throughout, didn’t ask any questions but walked up to Lo Dagerman at the end. I remembered her father’s work vividly enough to have her share her email address and take a signed copy of her book home.

I didn’t read The Writer and the Refugee until late September 2021, when the madness of the pandemic and the presidential election were receding; things felt possible again and so did writing for pleasure. I finished the book on the 21st, and wrote to Lo Dagerman a week later:

I have recently read your book, and it reminded me why Stig resonated so much when I first read him a decade ago. I’m grateful for the light it shone on the person he was and where his work arose from.

I’m writing to you because I know you do much to promote Stig’s work, and as a journalist, I’d like to explore writing about him. I would love to talk if you ever have time. There are facets of the search for a parent, through his work, that touched me quite personally.

From Lo’s book, it was the recounting of her search for her father that compelled me, more so than the story behind the play he wrote in the 1940s. An image in particular from the book’s beginning needled me:

“It doesn’t start with the typewriter, of course, but one day it appears. On my desk. Black and exotic in my little girl’s pastel-painted bedroom. It has Continental written on the front in faded gold lettering, and a hardtop hood that allows it to travel. My mother has put it there. I know that. I also know that it belonged to my father. Stig.

Who died, and whom I cannot remember at all.”

We met on October 20 in Georgetown, and though I intended to write about something entirely different, in reviewing the transcript I realize I returned to that typewriter at various points, asking her about that scene when she was a child, why her mother placed it there, in her room, and what became of the heirloom.

As with many stories that we’re drawn to, but can’t fully pin down, latching on stubbornly to an instinctive thread helps to stave off immobility. So I researched the typewriter, found out it had been purchased in 1946, and had cost 382 Swedish Kronen, along with various mentions of it in essays and remembrances on Stig Dagerman.

The sound of the typewriter, its staccato, its tonality, like heavy rain on a tin roof, that distinctive cackling like no other, was something that kept recurring whenever I read or mentioned the object in conversation. It was an unmistakable sound for generations, inseparable from an era not far gone, and now a figment of the past. It’s a sound I realized I had grown up listening to as a child.

In February I wrote to the Kungliga biblioteket, the National Library of Sweden, to find out about the typewriter’s final resting place. I’d already located its whereabouts in the library’s storage: reference code: SE S-HS Acc2019 / 42. Its terms of access: Produced for special purposes only. In storage, the reference collection stated, it occupies precisely 1.6 feet on the shelf. I got an answer in early March:

Thank you for your question. The typewriter was donated to the National Library of Sweden in 2019 by Stig Dagermansällskapet (Stig Dagerman Society). It is a part of the manuscript collection and only leaves the stacks on special occasions. Prior to that, the typewriter was in the care of the Stig Dagerman Society. Unfortunately, the Stig Dagerman Society was disbanded in 2019. At that point, Bengt Söderhäll was its chairman. If you want to find out more about how it was used by the Society I suggest that you try to get in contact with Söderhäll.

That week, I kept on pulling the thread, trying to find out about the object itself. Yes, a typewriter, but what type? I found there was a whole museum on the subject in Germany, in the city of Bayreuth, and contacted its director in my faltering German. He passed on my request and the images I’d shared of it, to an in-house expert. He answered on March 9.

Thank you very much for your message.

From the pictures, I would identify the typewriter as the “Continental 350” series produced for export.

This type is known as a “cheap” model without a moveable paper stop and without sheet support.

These typewriters had been produced from 1937 to ca. 1948. The price was around 185.00 German Reichsmark.

Even if this typewriter did not have special advantages it can be considered as a technical upper-class product.

The producer was the company Wanderer Werke (formerly company name Winklhofer & Jaenicke) located in the city of Chemnitz, Saxonia.

Kind regards

Günter Pschibl

Deutsches Schreibmaschinenmuseum Bayreuth

At the same time, following the National Library’s suggestion, I asked Lo Dagerman if she knew Bengt Söderhäll. She did, and they were friends. His answer took one month, and by then he was in Naples and occupied with the planning of the Stig Dagerman Prize, which I was to learn was given yearly since 1996 “to a person who, or an organization that, in the spirit of Stig Dagerman, supports the significance and availability of the ‘free word’ (freedom of speech), promotes empathy and inter-cultural understanding.” The first awardee was posthumous: a 14-year-old killed by racists.

A back and forth ensued until he gave me the date and time: April 27th, 10 a.m. Swedish time, or four in the morning on the East Coast. When asking for final confirmation the day prior, he wrote:

I will be awake after a müsli breakfast. I hope you can stay awake.

Looking forward to our talk,

Best,

Bengt

We spoke until dawn in the District of Columbia, and morning in Bengt’s home in Älvkarleby, a municipality a couple of hours north of Stockholm. I’d heard the name before and asked: it was only two miles “at bird’s flight” across the river Dalälven from the farm where Dagerman was born.

Bengt Söderhäll, I came to learn, had had the typewriter in his possession for a quarter of a century, and his reminiscences of it were like those of a fond friend. Together they had traveled across Sweden and touched many people over time.

Through the narrow gravitational pull of that single artifact, scenes started to coalesce: the visit from Dagerman’s widow, its role in a movie, and as the centerpiece of the museum on an island. How it had brought three generations together once. The pursuit of that old contraption, strange as it may have seemed, had led me to images I would never have found otherwise.

A device that symbolized all that persisted from that abridged life.

I. Journalists Are Always Late

News of Stig Dagerman’s suicide spread on the afternoon of November 4, 1954. From his suburban home in Enebyberg word came of the tragic end, at barely 31, of Sweden’s leading postwar literary light. A shock proportional to his reputation: “Everyone was talking about Dagerman; he was the genius of the decade,” remembers writer Per Olov Enquist in an essay. Or as Lo Dagerman writes:

“My father, the literary genius.

A sensation at age 22 with his first novel, ‘The Snake.’

A famous journalist at 23, whose book on postwar Germany, ‘German Autumn,’ becomes a classic.

Popularized through his occasional poems commenting on contemporary affairs.

The author of ‘To Kill a Child,’ one of the most-read short stories ever written in Swedish.

The originator of a powerful body of work, feverishly produced over a scant few years, ranging from fiction, journalism, essays and drama to satirical verse and poetry.

A leader among his generation of Swedish writers.

And then: Dies young at age 31. Tragically.

‘The Nordic Rimbaud,’ as the French later would refer to him.

My father — the mythical author.”

Hence his death, that November night, was assured the front-page for the following day — with one notable exception.

“As the facts circulated throughout the city’s press, the irony of fate was that Arbetaren was the only one to ignore it: everyone thought that Stig’s old newspaper already knew what had happened. This explains why, while all the other Stockholm dailies were announcing his death, on Friday morning, the issue I’d been editing during the night featured, in its usual place, his daily bulletin,” wrote journalist Mauritz Edstrom.

So it was that Arbetaren, the very paper Dagerman had joined at twenty, where he’d once been editor, where still wrote a daily column which he’d dutifully sent before ending his own life, ran his final piece, entitled “Beware of Dogs,” instead of their collaborator’s obituary. It ensured he did not fully overshadow his writing.

It’s an outcome that fitted Dagerman’s self-effacement, as well as his definition of the profession: “Journalism is the art of arriving too late as early as possible.”

He’d coined that phrase in a letter to his colleague Werner Aspenstrom, sent from Munich in 1946 while covering the devastation of postwar Germany for the Swedish daily Expressen. Stationed in the Allied Press hotel, Dagerman had soon grown wary of the role expected of correspondents — “They think that a small hunger strike is more interesting than the hunger of multitudes. While hunger-riots are sensational, hunger itself is not sensational, and what poverty-stricken and bitter people here think becomes interesting to them only when poverty and bitterness break out in a catastrophe.”

Steve Hartman, his translator, recounts how Dagerman was advised by a fellow journalist “with the best of intentions and for the sake of objectivity to read German newspapers instead of looking in German dwellings or sniffing German cooking pots.” The news was the Nuremberg trials, and rightly so, but Dagerman sought stories amidst the ruins of the bombed-out cities of the former Reich, chose to report from the cellars and meet those who dwelled there, to reflect on suffering and hate and culpability. He denounced both the mistakes of the Allies and the German politicians alike; the growing class divides amidst the destruction, and the selfishness of those it had spared.

“When every available consolation has been exhausted a new one must be invented even if it is absurd. In German cities, it often happens that people ask the stranger to confirm that their city is the most burnt, devastated, and razed in the whole of Germany. It is not a matter of finding consolation in the midst of affliction — affliction itself has become a consolation. The same people become discouraged if you tell them that you have seen worse things in other places. We have no right to say that: every German city is the worse there is when you have to live in it,” he wrote in German Autumn, his collected reportages.

Dagerman was only 23 and knew German through his first wife, Annemarie Götze, the daughter of German anarcho-syndicalist political refugees. They had married in wartime, to afford her the protection of a Swedish passport. Now, having written his first novel, The Snake, to critical acclaim the year prior, he’d purchased his own typewriter for 382 Kronen and moved on from his editorial role at Arbetaren to become a full-time reporter and writer. From then until his last, through the initial rush, the ultimate wane, all his writing arose and fell from that single instrument which inaugurated a new life full of promise.

II. A Father’s Heirloom

Lo Dagerman lost her father a month shy of her third birthday. She was the only child of his second marriage to the actress Anita Björk. It was from her that she received a belated inheritance five years later: his typewriter, left on the childhood desk.

It is a gift heavy with significance, which Lo recounts in her book from the perspective of the child she was then. “At eight years of age, things are simple. There is a typewriter that calls out to be typed on. So I learn how to peck on it using only my index fingers — still to this day the way I type.”

At first, she follows in his stead and the keys can be heard again, spelling the altogether different tune of a child’s deadlines: poems and rhymes for birthdays, Mother’s Day, and Christmas alike. She knows her father was a writer, and a famous one at that, though this is a mere fact, like that of his absence.

In her hands, it is at first a toy, a gift from the land of adults which children yearn to reach by counting half-years that will age them quicker, as if standing on the tiptoes of months. The childish age that seeks to forego all that is childish.

“I loved it, any kid would, because it’s an adult thing,” she tells me. “I was brought into adult complexities pretty early by my mother. I didn’t feel scared by that, I felt honored. Kids love when they are talked to not as little children, but as though they understand.”

Time brings greater awareness of just what she had inherited, a name, a past, a parent’s unwelcome fame.

“It was something that was always there because he died so shockingly, there were reverberations through Swedish society. People really remembered this writer because of his shocking death. So therefore, as a child growing up, or starting to attend school, people would know. They would ask ‘Are you related to?’ That would be a very, very common question.”

A famous father can be a minefield when you struggle to define who you are, or when he’s on the curriculum in high school and everyone reads his story To Kill a Child. But Lo doesn’t remember being in class that day, or reading his words, “It’s not true that time heals all wounds. Time does not heal the wounds of a dead child.”

Then there is the growing sense of expectation, that foreign weight that alienates you from yourself. “People know about your parents, and they look at you in a certain mind that maybe, you know, you would have some talent in this way or another. Or not.”

The symbol of it is the typewriter, her mother’s gift, laced with the risk of disappointment. “I think she was desperate to try to see in this child, something of Stig’s. There was, I’m sure, a hope, somewhere along the line that this child would carry some of this genius, have inherited some of this,” she says. “I carry with me my mother’s grief. Even if I don’t remember Stig, I grew up in a home with that grief, and it colored my life.”

Hers is a father she cannot evoke but that people measure her by. The steadfast leftist voice that denounced injustice, went against the grain and spurred debates with the belief “that solidarity, sympathy, and love are humanity’s last clean shirts.” When she is 17, Lo is asked to write a political article and dutifully obliges. “It was a dud. They had thought that maybe I would have something, but I didn’t,” she says. “It was pretty clear that that was not going anywhere. You could even see it as ending this period of the goddamn typewriter: ‘You gave this to me, this is what came out. Now you do whatever you want with it. But this is it, this is what I could do, and not more.’”

Lo will recount her estrangement from the heirloom half a century later:

“Even in my early teens, I write on the typewriter. For a brief moment in time, it is a tool for expressing my budding individuality and sense of identity. Then one day I set it aside, not to be used except for the most mundane of tasks. The typewriter is no longer a plaything, a tantalizing tool for reflection or free-roaming imagination. Instead, it has morphed into something entirely different. Something that brings intimidating performance demands.”

“‘Ah, Stig Dagerman’s daughter — do you also write?’ Hell no.”

So the typewriter falls silent again, waiting to be given new meaning. For Lo freedom and pressure meet on the keys, and in her adolescence the latter prevails. In that, she inversely reflects her father, who went from bliss to anguish on the typewriter as his career progressed.

There was more of the former leading to his time as a youthful correspondent, when, the summer before going to Germany, he holed himself up on Kymmendö Island, in the Stockholm archipelago, in the writing cabin built by the author August Strindberg. There, over the course of a summer, he writes Island of the Doomed, the story of a group of shipwrecks on a waterless island populated by giant lizards and blind birds. It’s one of the happiest times in his life.

It reads: “Another mooring rope had been cut, and now he could rise up like a balloon into silence and solitude. His limbs were filled with painful desire; as noted, he thought his paralysis had eased and suddenly found himself running. He felt as if he were swishing through the morning, his feet were like typewriter keys striking the unwritten sand, which had so often been rinsed by the waves.”

That summer Dagerman is one with his writing, as Lo explains to me. “It’s all documented in brain chemistry, it’s called flow. We are separated from ourselves; you just wander the moment, a pleasurable experience that becomes almost addictive. That’s where we want to be. He described it to a friend saying that he had never felt so happy as when writing that book. He felt like he didn’t write it, but that God did it for him, because it was automatic writing”.

But writing giveth and it taketh away, and after the astonishing output of four books in three years — a haul of two novels, a book apiece of non-fiction and short stories, and his first play — there comes what seems a natural lull. Yet Dagerman resents meeting the stubborn blank page. Seasons follow one another and are altogether different: the resounding success of German Autumn calls for a sequel, French Spring, with the opposite outcome.

“After Germany, the joy of writing was gone,” he would later write to his publisher, reflecting on the years that followed. “The foolish year in France may have been devastating. Roaming in solitude from place to place with a journalistic imperative in the backseat and a typewriter in my suitcase that ultimately grew so heavy with failure that I could hardly lift it.”

He is commissioned to write a dozen articles, of which he will struggle to produce less than half. His French is poor, the subject hard: France is victorious and decades from questioning its role in the war. He detests Paris, “A gigantic heap of historical souvenirs and luxury restaurants, agreeable for millionaires and alcoholics.”

“It’s a disaster,” as Lo puts it succinctly, and the lowest point of his first bout of writer’s block throughout 1947 and into 1948. With debts and guilt increasing he has to resort to pleading with Expressen to release him from his engagement, and somehow pay back the advance.

“Weary and unhappy I crisscrossed the French countryside without being able to work, unable to establish the necessary contacts, and constantly feeling an unbearable pressure at what was expected of me back in Sweden. (…) Perhaps I made of the success of the journey — and rightly so — a matter of prestige, but, all things considered, it might be more reasonable to put mental health before prestige,” he writes to his editor Ragnar Svanström, on July 4, 1948.

From his time “screaming in the Parisian desert” one notable encounter remains. It is at the heart of Lo Dagerman’s and Nancy Pick’s The Writer and the Refugee. Dagerman is the writer; Etta Federn is the refugee, a fascinating Jewish intellectual who is Pick’s relative. She is also a practitioner of palmistry, divination by reading the lines on the hand. The book uncovers the foresight of what she foresaw in those of the young Swede:

Paris, February 5, 1948

Analysis of Stig Dagerman’s hands by Etta Federn (extracts).

“The first impression given by these hands is that of a great timidity, whose origin can be found in an unhappy childhood. Unusually sensitive to suffering…

These hands are as passionate as they are controlled. The subject’s passions are rarely unbridled, but they seem to always incite him to burn. The subject will not undertake anything that cannot be done passionately.

The subject’s evolution is marked by great inner and external crises, by upheavals begun by momentum followed by a great leap.

It is remarkable that the subject’s combative spirit utterly fails him when it comes to his emotional life, he then needs to be taken in hand, he is then incapable of fighting, or even of asking or begging for help. From his first failure, he closes painfully on himself like a withering iris.

The subject is capable of feeling great suffering but derives no bitterness from it

Dagerman has had his crisis, now comes his great leap. Forced to produce something that will provide financial compensation for his failure, he turns to the isolation that served him so well in the summer of ’46. Not quite an island this time, but a peninsula, that of Quiberon, in Bretagne, in the village of Kerné, on the edge of the country, “in great loneliness in a locked room in a sleeping French village, with a continent between the writer and those he was betraying,” he’ll later write.

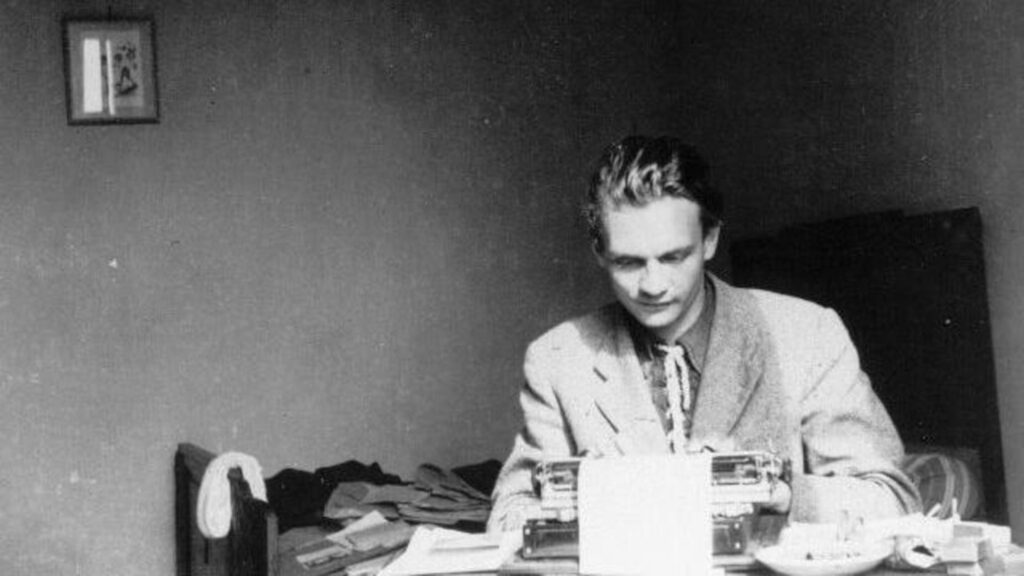

A single photo survives of his time there, facing his typewriter, the sheet of paper on which he’s typing bent backward, while he hunches forward, surrounded by papers and a plate on a narrow table, turning his back to a narrow bed strewn with clothing and more papers. There are various photos of Stig working, over the years, and in them, he often smiles coyly or looks warily at the camera. His fingers are always outstretched, awkwardly suspending writing for the image of writing, eager to lose himself again once the photo is taken. In the shot from Kerné he does not look away from the typewriter, his body is slightly askew as if mirroring the movement of the typewriter along the phrase. It is the portrait of a man absorbed by the page.

If writing has stuttered in France throughout the winter and spring, the extreme opposite occurs in Kerné. An entire novel is written in scarcely six weeks, and the result, A Burnt Child, is perhaps his masterpiece.

“A moment ago, there was fire. Now the tepid ashes warm our feet. A moment ago, there was blinding light. But now a blessed twilight cools our eyes. Everything is calm again. The volcano is slumbering. Even our poor nerves are slumbering. We are not happy but feel momentary peace. We have just witnessed our life’s desert in all its terrifying grandeur, and now the desert is blooming. The oases are few and far between, but they do exist. And although the desert is vast, we know that the greatest deserts hold the most oases. But to discover this, we have to pay dearly. The price is volcanic eruption. Costly, but nothing less destructive exists. Therefore, we ought to bless the volcanoes, thank them because their light is dazzling and their fire scorching. Thank them for blinding us, because only when we are blind can we gain full sight. And thank them for burning us, because only as burnt children can we give others our warmth.”

That summer he discovers that being on the brink releases him, exorcises doubts and guilt, wrings catharsis from the jaws of hopelessness. It’s a pattern he will come to repeat in his work, and later in his dealings with death.

He wrote: “The important thing for me is that when the inevitable failure comes, it hits me not like pain but as liberation because it also provides me the courage to escape into creativity and the art of writing. In the summer of 1948, I was aimlessly traveling from place to place in northern France, dragging with me a weighty writing assignment for a Swedish publication: a series of articles about French farmers. But the whole country lay closed as a clam to me and I possessed no knife. My saving grace became an escape into A Burnt Child, into the writing of a novel where, for as long as it lasted, I was unavailable to shame and discouragement.”

III. The Typewriter’s Keeper

Seventeen years later, in Älvkarleby, a boy is breathlessly reading A Burnt Child. That is no figure of speech: something in the novel asphyxiates him, the character who is his namesake, the muddied secrets that belie the prose’s cold clarity, and speak to queries that age is putting before him. His name is Bengt Söderhäll.

“I began to read A Burnt Child when I was 14. We lived in a little flat on top of the public library, so I wouldn’t even put on shoes when I went down. I read the bookshelves from left to right. The librarians were kind because I was allowed to also read adult books, books for grownups. So I read a lot of writers, but when I read A Burnt Child, I had to stop. Because the young man in the novel is also called Bengt. And when you’re that age, and adolescence is not too far away, and the line you are going to follow is getting problematic…and the question in that novel: Who is that? Who is mom? Who am I the child of?” Bengt says. He has spent the first part of his life in an orphanage, and something in the absences Dagerman has put in his novel resonates beyond what he can bear.

“So I stopped reading. I remember I just walked out into the forest to get some oxygen. I was almost being suffocated.” He’ll finish it only much later, but that first encounter with Dagerman will change him, “This is my personal history that I’m trying to puzzle together. And it’s mixed with Dagerman.”

Another scene cements the writer in his memory. It’s the image of his mother, fragile of health but steady in reading, listening to the radio while Bengt looked on. “And always, when there was something on about Stig Dagerman, she kind of nodded and looked a bit sad. And at the same time, happy, that a writer like him had lived.”

In time Bengt became a teacher and Dagerman was something he taught and discussed with friends. One day his musings about creating a Stig Dagerman Society made it into the local paper. Eventually, in 1987, he founded a library with his friend Urban Forsgren, dedicated to the author’s work. The Society had become a reality. This time it made national news.

“Two or three days later, the phone began to ring, ‘Could you please come and give a lecture about Dagerman?’ The first two, three years we spun around Sweden and talked about Dagerman at schools, high schools, to unions of all sorts and women’s organizations.”

Then, on the nearby island of Laxön, once a restricted military area, buildings became available for public use. The budding Society was offered a space. It opened in 1992. For the next 25 years, it would be known as the Dagerman Room, a one-room museum where the flotsam and the valuables of a literary career and two marriages converged. Thousands would visit yearly.

“From the beginning, it was an interest in the texts by Dagerman, that was my interest, to read for yourself and make your decision on what is good, what is bad, and what you know,” Bengt tells me.” But it became life and letters. It was letters from the beginning, only letters, but it became more and more life.”

On the haven of an island — which he’d been prone to seek — a composite of Dagerman’s various writing rooms started to come together. Each donation recreated his study, as if frozen in time, its pieces reuniting as they had once been when the author perused that book cupboard or consulted this encyclopedia. All that was missing was for the typewriter to regain its place on the old desk.

Then one day in spring the phone rang. “I would like to come up to the room. I have a few things, a few items that I’m bringing. Can we meet on Friday?” On the line was Anita Björk, Dagerman’s widow and one of Sweden’s most celebrated actresses, famous for her role in Miss Julie, which had won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1951. That Friday Anita Björk, who was nearing 70, got in her old-fashioned Volkswagen and made the two-hour from Stockholm to Älvkarleby bringing with her a large plastic bag.

“She came in there, sat down, and we talked. We had met before, we didn’t know each other that well, but enough. And she put this big bag against the desk,” Bengt remembers. “Then she took out a few things. And there was this fantastic machine, on which Dagerman wrote most of what he wrote, this typewriter, a traveler’s typewriter.” By then she’d preserved the memento for nearly four decades.

It was after she parted with his instrument that Anita asked to visit his grave. It had been moved posthumously in the 1960s from Stockholm, where they’d lived together, to his birthplace. Spring had reached the cemetery, and from the branches overhead tree sap had dripped on his gravestone. Anita went to her car and got a brush. “She came back and I fetched water and then we were laying on our knees taking away stains from Dagerman’s grave,” Bengt remembers. “Then we took a big bucket of water and threw it over it and it was like silvery granite afterward. To me, it’s such a beautiful memory. She was one of our most famous actresses. She was our Greta Garbo. She had that shimmering around her. And she was lying on her knees, cleaning her husband’s grave.”

They had been married for only a year. They had both been 31. Here was the gravestone of a man so young it was already older than he’d become, as his widow looked on, perhaps reading his poem carved in stone: To die is to travel / ever so briefly / from tree branch / to solid ground.

IV. Return to Älvkarleby

In 2016 Lo Dagerman returned to her past, to her father’s roots, to grasp his absence from the starting point. She flew from her home in the United States to Sweden, then drove north to Älvkarleby as her mother had done with the typewriter one spring, along the road lined with trees that winds through the village, passing her father’s old school, the church and the cemetery where he is buried, and onto the farm where he was born in 1923. She knew Stig had left her there one summer in childhood in the care of an aunt. Recollections of that time had started to swell since she had first approached his writing.

“This was a part of my heritage, of my history, that I hadn’t really looked at closely. And then when I read him, there is a whole world that opens up; there are my own memories of this. It puts a part of my life together, in a sense,” she tells me. “As I approached this material, I was able to open to what happened to him — in ways that bring grief and sorrow — to what happened to my mother and my father.”

It had been a long journey to meet him on the page — to reconcile with a heritage that had once been unbearable — of which visiting Älvkarleby was a stage a lifetime in the making. Lo doesn’t remember having read her father in high school when it was compulsory, and in a sense, she feels she never quite did until she was in her thirties. It was the age by which she had outlived Stig.

“Turning 31, there was a feeling of ‘okay. I made it, kind of.’ I waited a long time. The time was right. I was able to handle it emotionally,” she tells me. By then, she has made a life on another continent, she is married, has two children, and is a counselor with studies in psychology. “I can start to look at this because I can see that my own life has taken and served a trajectory.”

She started with his short fiction, of which the best is often set in that land of childhood in the countryside, the town, and its surroundings. Discovering it was a preface to rediscovering Älvkarleby.

“When I’m reading these stories, I have pictures in my head of the aunts, of the farm, of the people there, and of my grandfather,” Lo tells me. “All of that comes alive when I read them. It’s my own history that’s starting to be revealed.”

Dagerman had travelled the world but his hometown was never far from his inspiration. His characters often drew on the rural people he’d known, whether on the farm or uneasily transplanted to the city. There, too, return is both a desire and a reckoning. He may have left the farm but it never left his writing.

It was never more the case than in 1949, a carbon copy of the struggles he’d staved off with the marathon writing of A Burnt Child the year prior. “After having again failed to fulfill a writing job, needing desperately to find an idea to stave off editors and creditors, what saved him was the fertile terrain of his childhood memories,” Lo recounts.

When this latest crisis loomed, Dagerman returned to Älvkarleby.

He writes in an essay: “I found myself on an ocean liner crowded with refugees destined for Australia. My assignment was to get in as close contact as possible with the passengers to gather material for the setting and story of a film. This was a task that seemed simple enough for the first three days, but that after two weeks exposed the entire width of its impossibility. Art is among other things a form of freedom created by distance. But a ship is a prison surrounded by water. You cannot live tied to your subject matter and at the same time exploit it.”

“I finally gave up the script idea and fled into the writing of a novel. I traveled by a clipper across the Pacific Ocean in the company of a wool trader from Lille. In just five days, I would be forced to account for my expensive failure. So it was necessary for me to quickly mount a defense to help me through the difficult time that lay ahead. But the immediate task was to come up with a name for the defense,” or to put it concretely, a title for a new novel.

One morning during a stop in Fiji, in a setting as foreign to him as could be, he cut himself while shaving and remembered a scene from his childhood on the farm. He was the furthest he’d ever been from it, yet now it came to him, a plot developing on the journey to Honolulu, then San Francisco. By the time he arrived in Stockholm to face the music, he had brought back from Australia a rural Swedish narrative. He had, once again, repeated the formula of writing wrested from the brink of failure.

The title of the novel was to be Wedding Worries, and it would be the reason for Lo’s return to Älvkarleby decades later. By then she had not only reconciled with her inheritance, and read her father, but also found a way to make it her own whilst sharing it with others. It was while co-translating the novel that Lo decided to set out on her trip. “I sought to have insight into Stig, on my family and the place where he grew up. I visited the farm with the second story that had been added, walked by the barns and stables, breathed the air and plunged into the river below. Here I could see them all and hear them,” she writes. “For me, it’s a way to get closer to my father. I meet the menagerie of characters from his childhood, described and embellished with such love. It makes me think of the meaning of their acts, all the while hearing Stig’s tender and insisting voice.”

Translating is the way Lo says she truly reads, when she has to retain each part, when she internalizes the words to make them her own in her adopted language across the Atlantic.

“No matter the work,” she writes, “every time I enter a text and make it my own — word by word, one image after another — we find each other, Stig and I.”

Stig Dagerman was born at 11:30 on the night of October 5, 1923, in Älvkarleby, at the farm of his paternal grandparents. It was raining when they sent for the midwife. His parents, Helmer Jansson and Helga Andersson were not married, nor would they be. She left the farm two months later. Her son, from stories heard, describes it like this: “On New Year’s Day she went to the station with a small bag in one hand. She said nothing, but simply walked out of their lives. The snow whirled the old year away. She never came back.”

Stig would not meet her until he was 19, on his initiative. He was left in the care of his paternal grandparents.

There was no Dagerman then. Until the age of four, the boy was called Stig Halvard Andersson. In 1927 his father acknowledged him: he became Stig Halvard Jansson. His third name, the one he chose, the name that history retains, was one of his first creations.

The genealogy of it is painful; it blends the distance from his father, the absence of his mother, a litany of loss, and the need to write.

It happened in the 1940s; Stig was studying at the university in Stockholm when he received news that his grandfather had been murdered. It was nighttime on the farm and he’d gone out to the paddock to see the horses. Not long afterward he was heard screaming. He managed to stumble to the gate before collapsing, with seventeen stab wounds. A local madman was the culprit.

“The evening I heard about the murder I went to the city library and tried to write a poem to the dead man’s memory. Nothing came of it but a few pitiful lines, which I tore in shame. But out of that shame, out of that impotence and grief, something was born — something which I believe was the desire to become a writer; that is to say, to be able to tell of what it is to mourn, to have been loved, to have been left lonely.”

His grandmother would die of shock a week later. He kept writing.

“In school competitions, I had better luck, and in my graduation year I won a week’s holiday in the mountains, with a short story. But that trip ended in tragedy: I lost a very good friend and roommate in an avalanche. When I came back I knew beyond all doubt what I must be. I must be a writer. And I knew what I must write: the book of my dead.”

Dagerman was born then, a surname derived from the word “Dager,” “daylight” in Swedish. It was to be more than a pen name, or a pseudonym. He renamed himself in adolescence, in writing, and loss, and from then lived as, wrote as, and would pass on the surname Dagerman to his children.

Dagerman never did write the “book of his dead,” but in a way his daughter has. It is the book of her dead, of him.

It tells of a typewriter left on her childhood desk, of writing and of ceasing to write, because of him. But to the reader it’s all a matter of time — a lifetime — because by now it’s her that we’re reading to know him.

“Other than when I was typing as a kid, I hadn’t really been writing. I had been writing papers for university courses, and a thesis, but I hadn’t been writing,” she tells me. “And when we wrote that book, Nancy and I, I felt the joy of the writing. And it was that joy that also connected with him, although I couldn’t say that I experienced what he experienced when he said he was communicating with God. But I had a sense of flow, where you’re completely absorbed in the process, obsessed by the process, and that, I believe, is something that he yearned for, wanted, and thrived on. And hated when it was gone. I appreciated being able to touch base with that.”

Lo Dagerman could finally write: “His shadow also brings me peace.”

V. Our Need for Consolation

At the Gothenburg Book Fair, over the years, a man would approach Bengt Söderhall, always with the same query: “Did you bring the typewriter?” Then, being shown to it, he’d ask, “Can I sit there for a minute?”

“He could sit for half an hour, just like a meditation, in front of the typewriter, with his hands almost touching the letters,” Bengt recalls. “We have a lot of stories like that around this typewriter.”

Here Bengt stresses that he has no such “fetishistic ideas.” His work, however, bears resemblance to a pilgrimage: every year, for 22 years, he rented a van, loaded it with the Dagerman Room, and drove 342 miles to Gothenburg to install it at the city’s book fair. He would lay rugs on the floor, install the furniture, and recreate the ambiance of a room in the 1940s or 50s. The typewriter was the showpiece. Visitors would wander, stop out of curiosity, and he’d witness Dagerman’s enduring clout.

“A lot of people, ordinary people, but also writers, when they understood it was Dagerman’s typewriter, would say ‘Can I touch it?’ To me it’s kind of…” he says barely reserving his judgment.

Bengt respects the writer, and his writing, to a fault: they changed his life. He can do without the myth that surrounds him.

“Sometimes, with Dagerman, the shimmering is a big bit like James Dean: the young who died too early. The shimmering is so strong, that you forget to analyze what it really was what he did. I mean, you shouldn’t put Dagerman on a pedestal, you should remain in the spirit of Stig Dagerman, which is to look straight into the eyes.”

The myth itself, the myth of himself, in his lifetime, is part of what stifled Dagerman.

At the age of 26, the count read: six books, four plays, and hundreds of poems and articles. He has long been considered a prodigy and evokes epithets like “the Nordic Rimbaud,” a fatal simile with another writer whose precocity prefaced silence.

Dagerman will describe the crushing weight of expectation and self-doubt three years later, in a brief text titled Our Need for Consolation is Insatiable:

“We all have our masters. I am such a slave to my talent that I dare not use it for fear of discovering that it has been lost. I am such a slave to my reputation that I hardly dare write a line for fear of damaging it. When depression finally sets in, I become a slave to that as well. My greatest ambition becomes to hold on to it; my greatest desire becomes to feel that my only worth lies in what I fear that I have lost: the ability to squeeze beauty out of my despair, anxiety, and failings.”

It is not a lack of ideas that afflicts the young writer. From 1949 onwards, there are plans for as many as six new novels, “But he, who had once been so prolific, now found himself incapable of completing anything more than isolated chapters,” writes his friend Michael Meyer. In Swedish, writer’s block is called “writer’s cramp,” a stifling feeling you cannot shake off.

He’d grown used to bringing back writing from the brink, to feeling the edge of the precipice to spur him into a creative frenzy. After multiple blundered attempts on his own life, Dagerman committed himself to observation in a psychiatric hospital. Two years earlier, in A Burnt Child, he’d written about the main character’s botched suicide that reconciles him with the world.

The year 1950 held the extremes he’d lived out on the page. It had brought love, as Dagerman fell head over heals for Anita Björk, and with it came the hope of a new life, a new home in Enebyberg, and soon the beginning of a family; it had brought depression, the guilt that came with a painful divorce, and the feeling that writing had abandoned him.

The following year, he writes to Anita Björk, already pregnant with Lo: “It is a terrible experience, which I know you will be spared, to feel oneself disintegrate and sink when one is praying to be allowed to grow and climb. Now that the choice has finally come between living like a pariah and dying wretchedly, I must choose as I have done, because I believe that a bad person’s death makes the world a better place. God grant that our child may be like you. I have loved you, and will do so for as long as I am allowed to. Forgive me, but please believe me. Stig.” The letter was never sent. Meyer writes that it was found torn into small pieces.

When Dagerman finally finishes a piece it comes from an improbable source. The prompt is a request from the editors of Husmodern — housewife, in Swedish. The magazine’s title speaks for itself. He is to write something on the art of living for the magazine’s readers. Dagerman, fresh from slashing his veins and turning on the gas, gives them a harrowing and moving seven-page essay that matches anything he’s ever written: Our Need for Consolation is Insatiable. To Husmodern’s credit, they run with it.

It reads: “I have no belief and because of that I can never be a happy man. Because happy men should never fear that their lives drift meaninglessly toward the certainty of death. I have inherited neither a god nor any fixed point on this earth from where I can attract a god’s attention. Nor have I inherited the skeptic’s well-hidden rage, the rationalist’s barren mind, or the atheist’s burning innocence. But I would not dare to cast a stone at those who believe in what I doubt, much less at those who idolize doubt as if that too were not surrounded by darkness. That stone would strike me instead, for there is one thing of which I am firmly convinced: our need for consolation is insatiable.”

The essay seeks to discover a reason to live, amidst the ubiquity of its opposite. “I can free myself even from the power of death. True enough I cannot escape the thought, much less escape the fact that death stalks my every move. But I can diminish its menace to nothing by refusing to pin my life down to such precarious footholds as time and glory.” The reasons exist, yet frail, as a match’s flame, blown out by the same breath that would speak them.

Perhaps the final hope of the text lies in the very act of its writing, for an author who, alone every night before his typewriter, lost faith in words that gave him meaning.

From its inauspicious beginnings, the text enjoys an eventful afterlife he’ll never witness, it becomes popular abroad, is set to music in France, inspires a choreography in England, theater in Portugal, and six decades after being written catches the eye of a young director. His name is Dan Levy Dagerman, the grandson the author never met. Suddenly, the typewriter is cast in the starring part in the role of Stig Dagerman’s typewriter, opposite Swedish film star Stellan Skarsgård in the short film Our Need for Consolation.

Bengt brings the typewriter down to Stockholm for the occasion, and Lo Dagerman has it cleaned and repaired, then searches for near-extinct ink ribbons that will allow it to type again. It’s as good as new for its big break.

“The typewriter in the film and someone is typing on it, and the text of Our Need for Consolation comes out as Stellan Skarsgård reads it,” Bengt says.

“Dan had a really hard time. He felt very moved by the text, but…it was a difficult time for him to work with a text like that, in retrospect,” Lo says. “The piece itself has a turning point, where Stig writes about ‘the miracle of liberation.’ Dan wanted in his film to emphasize it, so that it would stand out. It was, of course, hard for Stig to hold on to the ‘miracle’ but it is the memory of it that infuses hope and a will to live. Dan stayed true to the text.”

It’s the closest thing to Dagerman family reunion. Despite Lo Dagerman not remembering her father, and her son Dan being born decades after his death, three generations converge around that typewriter, brought together by his creations: his writing, and pseudonym that became a surname.

VI. Endings

The Dagerman room closed its doors in 2019, the casualty of island weather. Cold and humidity were eating away at the old 1940s Arbetaren and Dagerman’s words were fading. The pieces that the museum had brought together were dispersed again. Some went to the local library, others came home with Bengt. There was the large book cupboard too large for relatives to claim, and the traveling typewriter as well.

“I had the typewriter in our house and I was somewhat nervous,” Bengt says. “I couldn’t protect it if there was a fire or anything, or it could be stolen. I mean, an item like that…”

While finding a more permanent home for it, he settled for some improvised camouflage. His safe was too small to hold the typewriter, so he hid it behind it, then both behind a large desk, with an additional layer of old clothes nearby to dissuade anyone from looking closer. “It was impossible for any thief to guess that there was something valuable there.”

Bengt still took it out sometimes, to take it to lectures, or show it to a curious guest. What he never did while for the time he kept it, he assures me, neither at his home nor before, in all the many years it was in his care — despite being a writer himself — was to type on the typewriter.

“Sometimes I thought it would be nice to write something on it, but I never did that,” he explains. “Because it was Dagerman’s, not mine.”

When asked if he’s ever missed the typewriter after they parted, Bengt only says “In a way.” Then he’ll admit he yearns for writing on typewriters. It’s something only those who ever used one could attest to, that feeling it left on the fingers.

“The typewriter is more of an instrument than a computer. You touch the computer with the skin, but a typewriter is a physical object with another concentration of feelings of tactility,” Bengt explains. And he remembers when he was young and would type away to the sound he made, “like heavy rain on a tin roof.”

It’s the sound Michael Meyer recounts on his visits to Anita and Stig in their home in Enebyberg. “It struck two and I would totter upstairs to my guest room. Even then he did not always go to bed. Sometimes he would climb the extra flight to his study in a small tower which rose above the house, and I would fall asleep to the sound of his typewriter.”

They had spoken late into the night, discussing theater, literature, and the state of the world as one does at that age. They had even discussed sports once Anita had gone to bed. Dagerman was a delight to talk with, joyful and impulsive in English, which he spoke well. And yet it was 1953, and the next year would be his last.

“This typewriter, alas, now held a very different significance for him from what it had symbolized when I had first seen him in 1948,” Meyer writes. “The tappings of the typewriter which penetrated from his room in the tower to my small guest room below were the efforts of a man to overcome a paralysis; a paralysis from he was never to escape.”

And yet he’d been charming all night. Keys might not sound different when they give us purpose and when they drive us to despair. The sound of Dagerman at his typewriter would have been the same as anyone else, give or take the speed at which they typed. And yet, with Dagerman, what you heard was the sound of him alive.

There would be one last flare on the keys, the prologue to a fifth novel. It was a door half-opened and soon slammed shut. Anita Björk recounts it in a talk: “I followed Stig’s struggle to write at close range. He stayed up late at night, sitting at his typewriter — each morning only to tear up the pages he had written. But one night in the early part of 1954, he woke me up carrying a tray with tea and lit candles. He had finished the first chapter of a major novel he was planning. I listened as he read a piece titled A Thousand Years with God in his tense voice filled with anticipation (….) Afterward, as Stig finished reading, we were both overcome by emotion. We were struck by the extraordinary reach of the piece, and by the possibility that now, finally, Stig might have broken through his own silence.”

“Everybody is saying that piece signals a whole new beginning,” Lo says. “It’s a remarkable piece. It’s nothing like what he has written before. It’s a whole new thing. He was on to something.”

It would remain a prologue, as expectations and debts converged around a depleted vocation. For a time too brief a man wrote on this typewriter, in so doing he achieved a joy such that he felt god was typing for him. Then he lost it. He ceased to be able to write, then gradually, to be able to live.

“There are many culprits, but a main one is that the publishing company at the time, they are demanding of him to write a novel a year. And he can’t do that, particularly not when he’s trying to find his passion again.” Lo tells me. “What Stig needed was a moratorium. There was a kind of naive ignorance on all sides, probably my mother as well, the expectation that this could just happen like that: now you sit in your tower and write.”

Meyer again recounts this ambivalence, the outward appearance, the expectations, making you oblivious to warning signs. “Anita Björk and Stig Dagerman were deeply and mutually in love; and whenever I saw him, during the summer of 1953, he seemed calm and content,” he writes, then adds, “He had dark moods, which I never saw; often he felt the overpowering need to be alone, and would get out of bed in the middle of the night, take the car from the garage and drive for hours into the night, as though he longed to enter the darkness and be swallowed up in it.”

Then one day he ceased to go out. He would still get in his car, still, turn the engine on, and then wait until the last moment in the garage. It was the first garage he’d ever had, an advantage of the move to Enebyberg with Anita. It was a long way from the house; some 50 feet to stumble back from afterward, after every curtailed attempt. He called it “death played in the garage,” a strange game in the night. “He was a gambler that needed to deal with death to exalt the price of life,” Olof Lagercrantz writes in his biography of Dagerman.

“He was obsessed with it,” Lo tells me. “Sometime in ‘53 or ‘54 that idea occurs to him. He has tried gas before, so he understands it. That last fall is when I think my mother and friends around him understand that it was serious. And there are all sorts of interventions that are tried to but that don’t work.”

“Somehow my life has come to a standstill, and I don’t know how I’ll be able to revive it. I can’t do anything anymore: can’t write; can’t laugh; can’t speak; can’t read. I feel like I’m outside the whole game. When I’m with people, I have to force myself to listen to what they are saying in order to smile at the right moments,” he writes in a letter to a friend days before he falls silent.

Alone in the garage, behind the wheel, Dagerman lets the engine run until the last moment. Then he turns it off, crawls out, and staggers back to his house. It’s salvation from the brink once and again, and like rehearsals in the theater he adored. “He’d grown used to grazing his own death. Suicide was part of his life, so to speak, rather than of his death,” writes his translator Carl Gustaf Bjurström.

The final rehearsal occurred around 2 a.m., on November 4, 1954.

As on other nights, the engine of the car was turned off, likewise, the open door, though now it remained ajar. This time he was still inside with the carbon monoxide.

Thereafter, there remains the typewriter. In 2019 Bengt and Lo discussed what to do with this obsolete machine that had been an instrument of work, a childhood toy, a suffocating heirloom, an actress in a short film, and the centerpiece of a nomadic museum. It would travel no more. Bengt took it to its final home.

“I wrote a letter to the National Library, saying ‘We have Dagerman’s typewriter, maybe we could donate it.’ I had a response within a quarter of an hour! From the chief librarian! I took the train to Stockholm and when I got there they almost bowed to me, because it was so special. There it can be shown and talked about. So now it’s safe, forever I hope.”

VII. Typewriter

Six months after speaking to Bengt, and no closer to writing this story, I was visiting a colleague in Prague when he suggested going to the secondhand bookstores. Writing was much of our conversation that day, and while he shared his latest project I admitted to the odd research I’d been conducting for longer than I cared to acknowledge. After all, the typewriter was neither a Steinway nor a Stradivarius, just a cheap model of an outdated instrument. It should have disappeared, like its obsolete twentieth-century brethren; gone the way of the zeppelins and gramophones to an afterlife or rust. Still, it endured.

Journalists of a certain generation, when I had told them about it, had reminisced about the rat–tat–tat of the newsroom, the clacking so different from typing on the present keyboards. And I remembered waking up to that same sound in my childhood home, one of my oldest memories. Those typewriters had stopped working, left in a pile hidden behind the sofa, never to be replaced by computers. Some people fall silent, some people choose to fade, and it is their choice, though we might feel we aren’t quite enough for them to remain.

Maybe I wanted to disprove that was all there was to be said. To gather proof of the infinite ramifications of what continues to touch people, even despite ourselves.We had reached the bookstore and were perusing old paperbacks in a basement when I found it. It’s the sort of thing that happens when you’ve been immersed in a story for so long. I waited until the seller had his back turned to examine it, let my hands hover over the keys, and even allowed myself a brief tap. It was a portable Continental typewriter, the same as Dagerman’s. You wouldn’t have thought it memorable.

Diego Courchay is a Mexican-French journalist covering culture and politics. He is an Associate Editor at the Delacorte Review, where he contributes to the Writerland newsletter. He has received the Robert L. Breen and Margot Adler fellowships for Innovative Journalism. His upcoming book, Pupil of the Nation, is out soon.