This story is published in collaboration with LitHub.

Philip Roth lied to me.

Twenty-nine years ago, I had an odd encounter with the celebrated writer and it led me to conclude one thing and suspect another. One, he liked to play with people for his own amusement and, two, he was on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

The story becomes even odder than that, but first, our meeting.

In March 1993, Roth had come to San Francisco to read from his new work Operation Shylock: A Confession before a sold-out City Arts & Lectures audience. City Arts negotiated an interview for my paper, The San Francisco Examiner. Roth haggled over the length, at first agreeing only to 30 minutes, an offer I refused. We compromised on 45 and arranged to meet in the lobby of his San Francisco hotel.

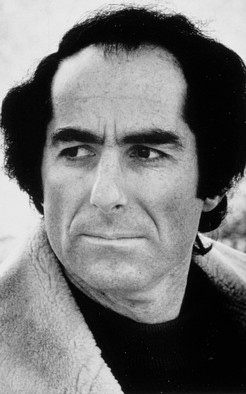

He and his then-wife, the actress Claire Bloom, greeted me politely. He was tall, slender and neat, his sharp head jutting from his shirt collar like a tomahawk. We settled in a quiet corner of the lobby, I, perched at the edge of a settee, he rigid and straight in a wingback chair. Bloom was directed to return in three quarters of an hour, to rescue him, I assumed, if he looked bored or unhappy.

I’d looked over many of his 16 books and prepared 25 pages of typed, single-spaced questions. A copy of Shylock and the publisher’s promotional materials lay on a table between us. I balanced a notebook on my lap.

The new book was our first subject. In it a writer named Philip Roth discovered that an impostor was running around Israel calling himself Philip Roth and espousing the tenets of “Diasporism,” a movement advocating that Jews give up Israel to repopulate pre-Holocaust Eastern Europe. The actual Philip Roth was distressed to learn these views were being treated by the international press as his own.

Into this fantasy, Roth introduced lively and colorful characters, including one he called “Henry Kissinger” who was, like the real Henry Kissinger, former Secretary of State under President Richard Nixon.

Roth held forth with gusto and humor, clearly enjoying himself. I asked my next question, a reference to the book’s “Henry Kissinger character.” He cut me off.

“What do you mean, ‘the Kissinger character’?”

Confused, I tried again.

He stopped me again.

“You keep calling him a character. It’s Henry Kissinger,” Roth said.

I tried a reset: You put a guy with Henry Kissinger’s name in made-up circumstances, then gave that guy things to say that the real Kissinger never said because the made-up circumstances never actually occurred. Right?

Wrong.

“The book,” Roth explained, “is not a novel.”

Roth and I had some friends in common and they’d all reported that he was extremely funny, a joker, in fact. We’d been getting along so well, I’d hoped that after this bit of Kissinger shtick, if I waited long enough, he’d shout, “Kidding!” We’d both have a good laugh and get on with it.

But he did not. And we did not.

Stunned and embarrassed, I silently berated myself for being the thoughtless reporter who’d misread her research, who’d blundered ahead on an ignorant assumption. But that self-doubt abated when I snatched the publisher’s publicity release from the table, and confidently read aloud the official Simon & Schuster marketing department’s introduction of Philip Roth’s latest—ta da!—“novel!“

We were safely back on Planet Earth.

As if in contention for Best Performance in the Misunderstood Writer category, Roth waved the paper away. “I didn’t write that,” he said. “I had nothing to do with that.”

In fact, we were neither safe nor on Planet Earth. We were in a fiction, set by Roth in the lobby of the Clift Hotel on Geary Street in San Francisco. It was there that I tossed 25 pages of questions into the air before the esteemed writer.

“I guess we won’t be needing any of that,” I said as the papers drifted to our feet.

Without looking back, we moved on to discuss Roth’s previous works until Claire Bloom returned, at which point he made no move to leave. He was having a good time and seemed pleased, his smile lines deepened, the tomahawk honed, his posture alert and buoyant. He sat taller in his seat, elevated with pleasure. Bloom appeared to recognize that look and took a spot by me on the settee. Roth held forth for another 45 minutes. Then we said our cordial goodbyes.

Back at my office, unsure of what I’d witnessed, I was certain of one thing: that in the face of Roth’s insistence, I’d temporarily surrendered all reason to the iffy conviction that the person who wrote the book probably ought to know what kind of book he’d written.

Still uneasy, I called the City Arts friend who had brokered the interview. Was Roth a drinker, did he take drugs? No and no, as far as he knew. We wondered then could his story be accurate. Shylock referenced international press coverage of the Roth double and his campaign. I looked for real-world corroboration, evidence, media accounts from the 1980s of a “Philip Roth” broadcasting politically indiscreet opinions from far-flung capitals. In those pre-internet days, neither our paper’s morgue nor the public library’s substantial archive had a word to say about any of this. Either no one covered it or it never happened. The latter seemed more likely.

So, I wondered: why had Roth played a practical joke on me? Where was the punch line? When was he planning the big reveal? What could he possibly be getting out of this?

What nagged at me most was a sense that there was something wrong with the man, that he was perhaps on the verge of a breakdown. On that instinct, I decided to press my editor not to run the piece. But just to make sure my decision wasn’t influenced by laziness, or a reluctance to labor over a distasteful job, I wrote it up anyway. In my story, I declared in no uncertain terms that Roth was lying. Beyond that, I allowed his own words to suggest that he might not necessarily be in the pink mentally.

I told my editor that in Shylock, which we’d now been instructed to view as “the truth,” Roth had described severe mental decomposition after taking the prescription sleep medication Halcion. Could he be lapsing back into a dissociative state? If it were even remotely possible that Roth were medically or otherwise impaired, would it be right to exploit him by publishing an account of his foolish ramblings? I thought not.

I killed the story. My editor said okay.

Flash forward three years to 1996. One year divorced, Bloom published her memoir, Leaving A Doll’s House, which limned a less than attractive portrait of her ex. As their relationship was unraveling, she alleged, he invoiced her, at $150 per hour, for his assistance over the years interpreting scripts she was working on. He also threatened to impose a $62 billion penalty when she tried to contest their oppressive prenuptial agreement. Further, she described a man who had become paranoid and was insisting she’d tried to poison him, among other accusations. Bloom also recalled how disappointed Roth had been with the unenthusiastic critical reception to Operation Shylock. She reported that shortly after our March 1993 interview, Roth checked into Silver Hill Hospital in New Canaan, CT, for psychiatric treatment, having suffered a breakdown.

Years later, I read that Roth’s authorized biographer Blake Bailey had weighed in on this episode in his book. Incensed by Bloom’s memoir, Roth had written a point-by-point, book-length refutation of her claims but was persuaded by friends to keep the response to himself, according to Bailey. His urge apparently unsuppressed, Roth retaliated later with the 1998 novel, I Married a Communist, featuring a scathing depiction of an unmistakably Bloom-like actress wife. The press reported widely on both Bloom’s and Roth’s books.

Curious to know if the biography had more to say about that breakdown, I contacted Bailey in May 2020, describing my Roth meeting. In an email, he allowed that Roth had been in a fragile mental state at the time I met him but attributed the behavior to Roth’s “imp of the perverse,” Edgar Allan Poe’s label for an unstoppable compulsion to do the wrong thing. Usually such compulsions result in negative consequences, but Bailey reported that Roth had felt rather “amused and pleased with himself” about spreading the false story about Shylock. I was taken aback and replied that anyone who could conceive to hoodwink some journalist just for fun could also feed equally perverse impishness to others, perhaps even to a biographer he’d personally selected to tell his life story exactly the way he wanted it to be told. (Roth had dismissed earlier chosen biographers, reportedly unhappy with the directions they were taking.)

All of this kept bringing me back to the work of writer Janet Malcolm, who famously observed that “every journalist who is not too stupid or full of himself to notice what is going on” understands that what she does is “morally indefensible.” Malcolm maintained that the interview is a disturbing consensual dance between reporter and subject. Each party exploits the other for personal gain, she submitted, but the journalist ultimately has the upper hand, “preying on people’s vanity…and betraying them without remorse,” enjoying the advantage of having the last word in print. In the Twitter-social media era, Malcom’s perspectives are to some degree outdated but, at the time, she spoke from experience. She herself had preyed on the vanity of a subject, eviscerating the reputation of psychoanalyst Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson so thoroughly in her 1984 book, “In the Freud Archives,” that he sued her in a highly publicized case.

In any context, it feels as if Malcolm’s observations say more about Malcolm than about journalists generally because while journalists can take advantage of their subjects, they don’t have to and, in my experience, usually don’t.

Malcolm, however, doesn’t concern herself much with subjects who take advantage of journalists. Roth, arguably a bit off his game, toyed with me but to no avail. Nothing he told me made it into print (until now). If there is a last word on this, it would be best characterized as a withholding. His practical joke, and the instability from which it could well have sprung, were not publicized, but neither was his book, in a historically book-buying town. And for a well-known writer, getting the word out about a new book would be the only reason to bother speaking to a journalist. Because Roth so obviously lied to me, our entire morally indefensible, exploitive consensual dance—from the negotiations over its duration all the way to the absence of a tangible result—turned out to be a big waste of time, with no personal gain for either of us.

As for the Bailey-Roth relationship, subject Roth was the powerbroker dangling keys to his trove of private papers. By outliving Roth, Bailey’s book would supposedly have the last word. But in light of Roth’s recognized penchant for “perverse impishness,” exactly whose last word does the authorized biography represent?

A year after my interaction with Bailey, the story broke that he had allegedly groomed young women—at the New Orleans middle school where he taught—for sexual purposes and, in at least one case, allegedly committed rape. Suddenly it didn’t seem accidental that Roth, a man accused of treating some women pretty badly both in life and in print, should have hand-picked a biographer who would himself be accused of sexual abuse. The allegations prompted an abrupt withdrawal of the recently published Philip Roth: The Biography by its publisher, WW Norton and Company, which pledged to donate to “organizations that fight against sexual assault or harassment and work to protect survivors” the exact amount of Bailey’s six-figure advance on the book.

Janet Malcolm notwithstanding, for a long time, I’d felt pretty good about protecting Roth from his own infirmity. (Or mischievousness?) Then, years later, I learned he’d made the same Shylock non-fiction claim to at least one other writer, Esther B. Fein of the New York Times. In her March 9, 1993 piece she quoted him: “As you know, at the end of the book a Mossad operative made me realize it was in my interest to say this book was fiction… So, I added the note to the reader as I was asked to do.” His “Note to the Reader” begins, “This book is a work of fiction,” and ends, “This confession is false.”

Roth whined further to The Times that critics had long accused him of writing autobiography rather than novels. Now he was writing the truth and “they all insist that I made it up… I can’t win!” he protested.

“I can’t win!” That’s Roth’s recurring plaint through a long career of critical successes, awards, honors, and general approbation. He was the middle-class boy from Newark who’d made good. Yet because some pundits had the gall to question whether his fictions came from life, he had calculated by some measurement known only to Roth that he could not “win.”

The winner coyly dismisses his wins. Was it a Machiavellian tactic to generate sympathy for someone who needs none? It seems just the kind of thing Roth was referring to when, according to Bailey, he requested of his biographer, “Just make me interesting.” Not, “Get it right.” Not, “Tell the truth.” Perhaps that would be the understandable position of someone who knew there were secrets in his closet, skeletons he could assume would someday fall out and rattle away long after his death, leading him to plead with a wink that his biography stress above all that, however flawed, Roth was “interesting.” It’s as if Edison had told his biographer, “Don’t forget to say that I was inventive.” Perhaps the canny Roth judged Bailey as just the guy who would write the biographical apology for boys-being-boys that “interesting” Roth hoped for.

Bailey admitted to me in writing that Roth could be “mean.” And people who had known Roth longer and better did, too. A writer friend who knew Roth over a number of years put it bluntly: Of all the many writers he knew, Roth was the one “with the worst character. A bad man.”

Meanness and mental instability (and a contemporaneous stay at a psychiatric hospital) could explain the gratuitous clownery and the ill-advisedness of the joke he told me. Still, Roth’s gambit smells even worse today than it did decades ago. In fact, the media’s Shylock coverage of the day had been respectful. No one judged Roth’s non-fiction claim to be the signal of a great mind publicly unraveling. Whether he was unraveling or just having a little fun, the book (in my view still one of his best) continues to speak for itself, a last word of sorts, beyond ex-wives, beyond authorized biography, and beyond the unauthorized biographies scheduled to follow.

Much like Malcolm’s villainized journalists, Roth continues to enjoy the benefits of leaving behind a meticulously crafted, respected and admired voice. Every one of his more than 30 books is a last word, impervious to Twitter’s or anyone else’s pushback. Just ask Claire Bloom.

Even Bailey got his last word. He’s denied all allegations and Skyhorse Publishing released paperback, ebook and audiobook versions of the biography in June 2021.

All of that aside, in 1994 I was delighted to hear that Operation Shylock: A Confession appeared on the Pulitzer Prize finalist list and went on to win the PEN/Faulkner Award.

For fiction, by the way.

I’ve been able to find no evidence that Roth complained to either the PEN/Faulkner judges or the Pulitzer committee for nominating him in the wrong category. Of course, that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.