Part 1 of 2

I first met Amadou Camara during the inaugural week of my freshman year at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, in 2011. We were gathered in the chapter room of a fraternity called Theta Chi, to participate in a piece of that ever-sacrosanct ritual: rush—the three week whirlwind of meet-and-greet roulette that kicks off the first month of the academic year on many American college campuses, each five-day period bookended, for men anyway, by a slate of beer- and testosterone-fueled events that often seemed to spiral just out of anyone’s control.

For those not steeped in Greek culture, rush is a tryout of sorts for prospective members of the single-gendered social clubs that dot the undergraduate landscape. Sororities have their own, equally-baffling version of this custom, of course, with fewer alcohol-related university damage reports and more song-and-dance routines.

Each year, freshmen arrive on campus only to be bombarded by recruitment messages from dozens of these organizations, each with their own particular brand of post-adolescent charm. We—my friend Brendan, a loud, barrel-chested Irishman from Chicago, and I, who had only met a few days earlier—had, after much deliberation, ended up at Theta Chi.

Though the original building has since been torn down, it exists in my memory as a run-down mid-century chalet, with a sloping roof and spacious front balcony emblazoned with the house’s letters: ΘX. It had seen years of hard use, with chips and cracks in the fading wood-paneled walls. At the top of a central staircase sat a lofted living room, with a large reindeer head staring out from above the stone-lined fireplace. We affectionately called him Lou (short for “Caribou Lou”), and during parties outfitted him with various hats depending on the night’s theme.

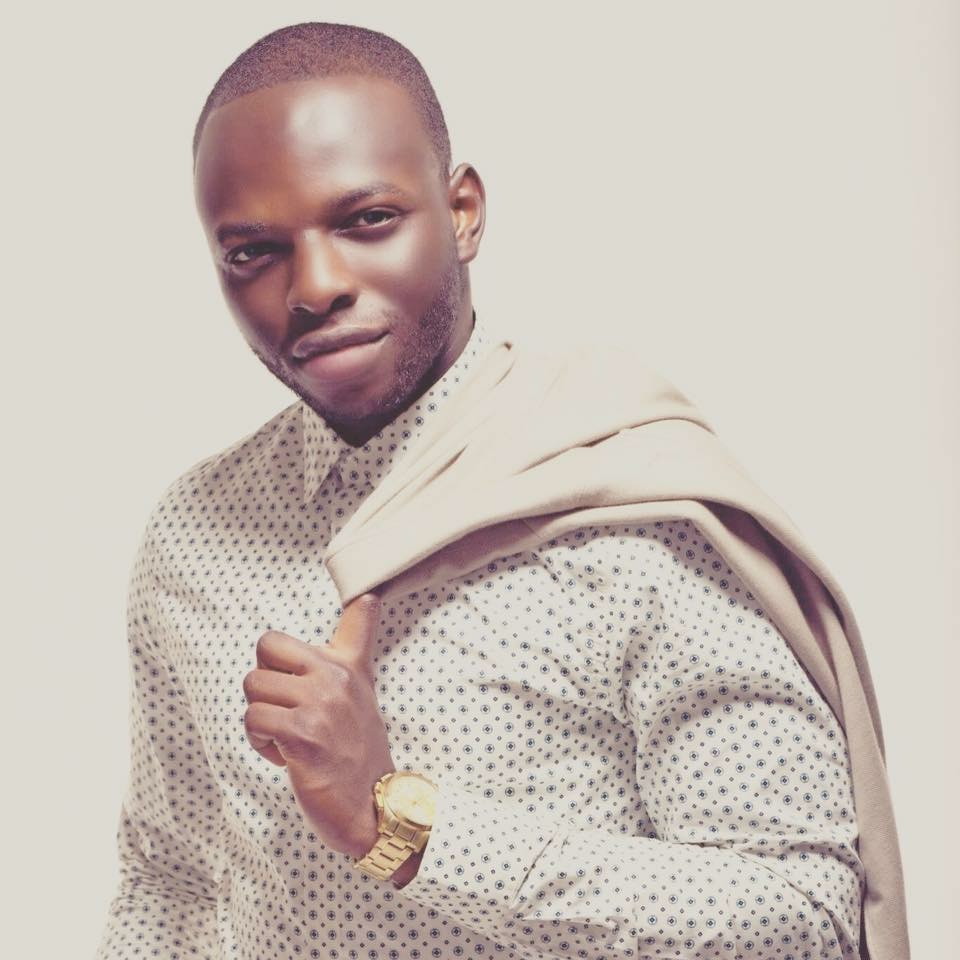

That day, Amadou strode in wearing a gray Tom Ford suit and designer shoes that seemed to shine in the way most expensive things do—that is to say: he seemed rich, and we noticed. He had this way of sucking up every bit of energy when he walked into a room, of connecting with each person he came across as if he had known them for years. Amadou accomplished this by shaking hands with everyone he met—and I mean everyone. It was a ritual I would see repeated hundreds of times over the next several years, one we would come to imitate and parody and even mock at times. He would start at the outer edges of a crowd, usually with someone he knew. “Son!” he would say, a single staccato syllable that stopped whatever else was happening at the time. He spoke in an accent that came and went, without a clear origin that we could discern, at least at first.

From there, Amadou moved inward, at each stop initiating a minute of awkward small talk that always ended with an innocuous yet somewhat revealing anecdote. The next time he saw you—and he was always there, at bars and restaurants and parties, in the library and on the street—he’d greet you by name, and remember that piece of information you were sure he would forget. Amadou was one of the few black faces on a mostly-white campus, with big, trustworthy eyes and an infectious grin. He had huge hands and an athletic build, but never seemed imposing, even when angry. He appeared to us an adult, at once above the fray of our adolescent hijinks yet somehow present for each moment of them.

In the months and years to come, we came to rely on him for all manner of things. When we needed contributions for a charity food drive that one of the sororities was conducting, Amadou was there with a connection for fifty-pound bags of rice. Another time, he got us a whole suckling pig for a gameday barbecue—with an apple in its mouth, the whole nine. We knew better than to ask questions. He didn’t even eat pork—Amadou was Muslim, we would soon discover, and kept a halal diet. This also meant he did not drink, despite his constant presence at events that centered alcohol.

This was 2011 at the University of Wisconsin, which had assumed the runner-up spot in Playboy’s annual party school ranking after being knocked out of the winner’s circle the year before by the University of Texas at Austin. The rest of us were drunk on cheap beer and youth and experiencing everything for the first time, lost in the spectacle of independence and the feeling of immortality that comes with privilege and a life that’s all future and no past.

Those first few years on campus were revelatory in all the same ways an American college experience is engineered to be, especially for a kid like me, from a rural part of the state. My life before eighteen was shaped by the sort of bucolic emptiness that defines much of the post-industrial rural Midwest—open space and wide skies surrounding a boarded-up Main Street, with a big box warehouse or dollar store on the outskirts of town. Drive ten miles in any direction and you’ll find a similar scene. Most everyone I knew worked to build and repair physical things—farmers, mechanics, carpenters, electricians, and the nurses and teachers and truck drivers necessary for a modern society to maintain itself.

But here, at a state flagship research university with a multibillion-dollar endowment, I met people who were trying to create a life not of reaction but of thought, of criticism, of new ideas and clashing worldviews that engulfed me immediately and never let go. I was good at making friends—to this day, it’s the only thing I can really say about myself with certainty. And at Theta Chi, life was a whirlwind of future journalists and architects and musicians, future scientists who would study politics and computers and the environment, future businesspeople, entrepreneurs, and medical professionals.

And Amadou Camara.

Over time, he became a friend, someone from whom I knew what to expect and whose rough edges I could locate, and reliably avoid. But no matter how close we became, there was always a gulf between us that I couldn’t quite pierce. And as I peeled back the layers of artifice that Amadou had knowingly wrapped himself in, it became increasingly difficult to separate the man I knew—thoughtful, loyal, and kind to a fault—with the naked ambition and pathological risk-taking that our friendship would also reveal.

Certainly, I never expected to discover, years later, that my friend was running one of the largest drug rings in the Midwest.

He was a Finance major, and talked often about his plans to work in private equity after graduation, which seemed to provide some kind of explanation for where all the money came from. We were never sure what his parents did, or where exactly he came from, though over time we would piece together clues and rumors to approximate a backstory that seemed to grow with each retelling but was never satisfactory.

At the time, the only thing approaching an origin story we had for Amadou was that he had been born in a West African country named The Gambia, and left with his family a few years later. The timeline matched up with a military coup in the mid-90s, a clue that hinted at a personal history that, for my friends and I at the time, was riddled with rumor and intrigue. He kept a faded picture in his wallet, one that showed his family—an older sister and his parents, a young Amadou standing at the center—outside what appeared to be a small farmhouse built of white stone. He’d used the word “refugee” to describe his childhood, but didn’t like to talk about it. “Of course,” I would say. It sounded tough.

And, given this personal history, we always noticed when he wore designer clothes and drove luxury cars and bought rounds of drinks for an entire bar.

He would throw these parties—these parties—at rented-out bars and rooftops and even once an empty apartment building, charging $10, $20, or $30 a head and donating the proceeds to charity. At least that was the pitch. Amadou was a genius at the sort of social engineering required by these ventures. He had set up a series of collectives for the purpose of planning—and more importantly, hyping—such events. One group he formed was affectionately called “The Trust,” envisioned as a professional network of ambitious men on campus, most of them Black, who decided to take a mutual stake in each others’ success. In photos they would pose in a semicircle, looking straight down at the camera with a stern expression, one hand outstretched. “Pay up,” the gesture seemed to say. It was only later that I would learn the organization was a legally registered LLC. “The family business” Amadou called it, though to this day I’m not really sure how it worked.

My first experience with this group came in the form of a year-end bash to close off our freshman year: “Twerkfest.” It wasn’t uncommon at these events to spot NFL or NBA players mixing with throngs of college-age women, big-name musicians stopping by on their swing through the Midwest, and even a few appearances by local politicians looking to burnish their street cred with a persuadable voting block. At the time all of these things remained, to me, incredible feats of social prowess. To call it an eclectic crowd would have been an understatement—but then again, everyone seemed to agree that was their whole raison d’être.

This particular event occupied what was normally a spin studio on the second floor of a modern mixed-use apartment building overlooking campus’ main drag, University Avenue. One day, Amadou admitted to me years later, he was walking down that street and glanced up at the glass-encased mezzanine. “I looked up, and it sort of became this aspirational thing, holding an event up there,” he said. “So I made it happen. I can be a hard person to say no to sometimes.”

Part of this inclination to appease Amadou was his almost supernatural ability to perform the back-of-the envelope math necessary to take an initial investment and make it grow. “Around that time of my life, making money was about the only thing I was motivated by,” he told me recently.

As our group arrived that day, and stood behind the glass rotunda that served as an entranceway to Twerkfest, everyone gathered inside seemed to look over in unison. Amadou was wearing a crisply pressed white tuxedo, a gleaming silver Rolex watch on his wrist. “Are you going to say something?” someone asked, as others began to scan the room for a microphone. But Amadou didn’t need one. I’ll never forget the smirk he gave as he pulled out a brick of cash—$1,000 at least, or somewhere near there—and walked it inside.

“Open bar!” he yelled, sidestepping the crowd as it surged.

***

When I tell my coterie of college friends that I’m retracing Amadou’s story, their reaction is never the surprise I anticipate. “Good,” they say, registering the news as if it were an inevitability. “It’s the best story I know.” For years, each time we’ve been together, we’ve relayed snippets back and forth, bits and pieces of conflicting accounts and persistent memories. Some of them still insist that Amadou had a full-ride football scholarship, but lost it his senior year of high school after a knee injury. Even they acknowledge that this may not be true—“That’s what I heard,” they’ll shrug. It took me years to finally commit to reporting and writing Amadou’s real story, in part because of the incredible work that I knew it would take to unravel the competing narratives at play and properly source each claim. This account, nearly two years in the making, is based on dozens of interviews, hundreds of pages of court documents, and numerous archeological investigations through the nearly decade-old communications of my friends and I.

My entrance into Amadou’s inner orbit began at some point after I began my sophomore year at UW. Several other members of my pledge class and I had moved into a tiny, brick-lined apartment above a Mexican restaurant near campus, which wafted the smell of roasted pork shoulder and fresh tortillas in through our open window every morning.

Theta Chi was around the block from that apartment, a brief walk on a good day. The House was our gathering place, it was where we came together to eat and study and throw parties, and everyone who wanted one had a key. On Friday and Saturday nights, there was no need to ask where your friends would be—they were at The House.

It was around this time my Theta Chi classmates and I—a dozen of us from the previous year’s pledge class, now full members with free rein to come and go as we please—came to realize the appeal of something like The House. Stripped of all the adolescent charm of its liquor-stained floors and pockmarked walls, this was, at its core, a system of interlocking economies, each operating in service of a larger whole. A fraternity, after all, exists as a government in miniature: levying taxes, providing a framework to organize around common issues and regulate the various industries which tend to naturally occur in such spaces. Amadou, for his part, seemed to be involved in all of them.

If you needed help with schoolwork, he was there with a recommendation for a tutor—I know someone who works with the football team, just let me call them. He always knew where the best deal was—Yo, my friend is getting rid of a couch, let me hit them up. When you were planning a party, there he was—I’ll roll through with the speakers at like, 8. And, perhaps most importantly, he knew where to find the good drugs—Son, I got you.

He knew someone who knew someone. That was his skill, his identity. And we put it to good use.

***

Near the center of every fraternity’s social scene is its drug dealer. It was through Amadou that I first met ours: an affable, gravel-voiced caricature of a man named Mike. He was anywhere from twenty-five to thirty-five years old—it was hard to tell. Every fraternity has some version of a Mike—likely a grad student, or maybe a person who works at the university, someone who took one step out into the “real world” and doubled right back in through the open door.

It was the night of our first social of the year, a warm, early autumn affair with our sister sorority, Alpha Phi, scheduled for a rooftop bar in downtown Madison. I had a pounding headache that even an afternoon nap couldn’t shake, something that, now, would surely sideline a night of heavy drinking but then was nothing more than a slight inconvenience. I had purchased weed a few times in high school, but this time I was looking for something a little stronger, something to make me forget the pain coursing through my frontal lobe. I thought Mike might have some pharmaceutical expertise to share.

As I knocked on the door to his room, a small suite on the fraternity’s third floor, I could hear some commotion on the other side. It was clear there were others in there, and when Mike cracked the door he seemed wary of the new face: “Who’re you?”

“Amadou told me to hit you up,” I said, explaining the situation.

Without saying a word he shut the door, and returned a few seconds later to deposit two chalk-white pills in my hand.

“Try these. Let me know what you think.” Before I had a chance to respond, the door closed and the commotion inside resumed. After a second of hesitation, I tossed the pills back and returned downstairs. It seemed harmless enough.

The rest of the night was a blur: bright lights and swirling music, a series of moments unstuck in time. I took the airy feeling and dissociation as evidence that whatever was in those pills had worked. Others were more blunt about the situation: “I remember that; you were fucked up!” one of my friends remarked when I brought it up recently.

The following day at The House, Mike spotted me cleaning up downstairs and asked how I felt. He was wearing sweatpants and no shirt, or shoes, a feat of courage given various fluids coating the checkerboard-tiled floor.

“Fine,” I said, “And hey—thanks again for last night. What were those?”

He let out a deep belly laugh that quickly turned into a rough smoker’s cough, and clapped me on the back. “Vitamin C.”

***

After that incident, we became friendly. It was through Mike that I began to see Amadou with increasing frequency. When it came time to sign leases for the following year, Mike moved in with two of my friends and I landed in another apartment with Brendan and his “little brother” in the fraternity, John, who we knew was also close with Amadou.

We knew John (I’ve changed his name here to protect his identity) was selling weed; Mike was still around, but his status—with the fraternity, with the university, with the law—was somewhat fungible, and he had always tended to hover somewhere on the outskirts of our social circle.

John was a little easier to read. His room had a separate entrance, and all that we asked of him was that his customers enter through the side door. Plausible deniability, or something like that.

We put together quickly that Amadou was involved to some extent. He would arrive unannounced at all hours of the night, and have these long, belabored discussions with John. They were closer to a corporate earnings call than to an episode of The Wire, complete with complicated spreadsheets to track expenses and income and projections.

Amadou and John trusted us and spoke openly, but it wasn’t as if we paid much attention to what was happening at the time. It seemed like an innocent-enough side gig, selling pot to our brothers in the fraternity.

Meanwhile, Amadou was also conducting a brisk business planning parties for various charities and nonprofit groups around campus. Ever the social striver, Amadou seemed to enjoy that rotating cast of characters. These were fairly standard affairs: Special Olympics or St. Jude’s or The Alzheimer’s Association or another legacy organization would cover the up-front costs, and Amadou, as well as anyone else he looped in, would get a cut of the proceeds. The rest went to a good cause. It was, we all agreed, a win-win.

The timeline of these events is somewhat murky, but I remember my introduction to one of these benefits as a Halloween Ball for UNICEF sponsored by Theta Chi. Amadou had rented out a nightclub for the evening—one of those provocatively named underground blacklight venues that are catnip for the college set. I’m not sure what it’s called now, but it’s seen past lives as both Liquid and Segredo (Spanish for “secret”). We had, in an attempt to class up the place, enlisted the help of a cross-section of the university’s sororities to help decorate the space with spiderweb streamers and miniature skeletons—your typical discount Party City fare. The plan was to encourage open attendance and charge a $10 cover fee, but as anyone who’s organized social events for drunk college students can attest, unpredictability is the only constant.

I can still picture Amadou’s face when, just as the party got rolling and a crowd started to form on the dancefloor, a contingent of Madison Police forced their way inside and stopped the music mid-song. The cops were performing what we colloquially referred to as a “raid”—a routine inspection to determine if a bar is properly checking IDs in order to weed out those who hadn’t yet reached drinking age.

Security at the venue had not been doing so—we had no idea, or at least that’s what we told ourselves—but either way the night was over, and the bar was to be shuttered for a short period until the owners could be dragged in front of the municipal Alcohol License Review Committee.

We filed back to The House, hoping that word of our run-in with the law wouldn’t get around to the school, or to the other houses. A bust like that didn’t bode well for future parties—what sorority would send their freshman and sophomore members to a party knowing that they were at risk of being slapped with an underage drinking ticket?

Still, it wasn’t five minutes before Amadou barged in, stack of cash in hand, a celebratory grin spreading slowly across his face.

“How did you still get paid if the event got shut down?” someone asked.

“Son, I always get paid,” he countered.

Amadou had saved us, it appeared, by collecting a list of people who paid, checking their IDs himself. This backstop meant we were legally protected from any repercussions created by the venue’s mistakes—including the failure to properly ensure anyone else entering the bar was twenty-one or older.

But there was another wrinkle. After a careful look at the numbers, someone noticed that there were substantially more names than people who had attended the party, especially given its short half-life. The names, too, didn’t match up with anyone I, or any of us, knew—and chances were high we would know the people attending our own party.

The names on the list, we finally concluded, were not real people. When a few of us asked Amadou about this discrepancy, he admitted in hushed tones that this was an easy way to launder money from his campus drug business. He called the practice “washing”—as in, “I had to wash up some cash”—and it did appear to present the perfect cover.

From there, the parties only got progressively bigger and more elaborate. At the same time, Amadou made ample use of the social capital he was building—both for himself, and for the fraternity. After a while, people came to associate Amadou with a good time, and many began turning to him for help throwing their own parties.

Word quickly spread. “Son!” Amadou says now, when I ask about what went into these events, “You can’t buy good press.”

Each component of a party could be broken down, he figured, and profited from. So Amadou taught himself the finer points of live DJing, and gathered a group of local musicians to form a collective of sorts that could be contracted for campus entertainment purposes, with Amadou skimming a percentage off the top. He called it Team Africa. That year, the venture got an unexpected boost—Montee Ball, the UW football legend and one-time NCAA career touchdown record holder, was arrested at the university’s annual end-of-year block party, Mifflin, while wearing a Team Africa T-shirt. It seemed natural to discover this way that Amadou had been friends with the NFL star for years.

The images of Ball’s arrest, which included a clear view of the T-shirt, were captured by a Wisconsin State Journal photographer who was serendipitously present at the time, and beamed onto thousands of screens over the course of the next week. It was the sort of press that, well, you just can’t buy.

For the most part, my immediate group of friends and I weren’t directly involved in the business aspects of these ventures, but we sure made use of the perks that came along with our newfound social status as Amadou’s fraternity brothers.

What we did know of the operations, though, was the impressive network of investors he was building. Wealthy kids seem to reproduce at a frightening pace in the Greek system, and Amadou was an expert in parting these budding bourgeois from their money.

My friends and I, on the whole, had a more working-class sensibility, and joked about this constantly. “Redistribution,” we called it. “Reparations,” even, though I should add that through all of this Amadou always paid back the principal on these investments—with interest.

Chris, our fraternity’s indomitable social chair, was one of Amadou’s principal party planners. He was a New England prep school product who always looked like he was posing for a Brooks Brothers ad—boat shoes, cable-knit sweaters, and, of course, pastels—that vintage, self-assured Ivy League look that was especially distinct at a place like Wisconsin. At the time, he was our eyes and ears in Amadou’s social circle, which conspicuously included a number of varsity and professional athletes, campus leaders, prominent local musicians and the loudest, most boisterous members of seemingly every fraternity. Chris would later make use of his time planning parties with this group and pursue a career as a promoter for various high-profile bars and clubs in Chicago and New York.

Looking back at the pictures now, though, he cuts an interesting contrast with the group. To put a finer point on it, he was a small white kid who hung around a group of black men, a good number of them of them Division I and professional athletes. My friends and I listened with wide-eyed wonder at his stories: red-eyes to Los Angeles and New York City for the weekend, deep-sea fishing off the Massachusetts coast, penthouse parties with panoramic views of campus.

But Chris’ magnum opus, as far as I’m concerned, came in the form of an off-campus bash we threw in the spring of my junior year, an event we still affectionately refer to as “The Field Trip.” The University, at the behest of the uniquely detested—at least among Greeks on campus—Dean of Students, Lori Berquam, had decided to cancel Mifflin. I’m sure this seems insignificant by most people’s standards, but to us at the time it was a gross infringement on what we saw as our personal autonomy—just the sort of nebulous concept a group of highly educated, yet poorly socialized eighteen- to twenty-two-year-old men could appropriate as a political issue.

Our chapter held a series of tense meetings to discuss contingency plans. It was at one of these gatherings that brilliance struck, in the form of a quiet freshman who often sat in the back row and rarely spoke up. “Why don’t we just hold an event somewhere outside of town?” he asked, the implication clear—if we left Madison, neither the city nor the university could take retaliatory action for violating the rules they had set days earlier to prevent crowds from gathering on the final Saturday before finals week.

It was the perfect cover.

So Chris and his crack team of party planners got to work envisioning just such a party. The university quickly got wind of the plans, and moved to shut it down, but later acquiesced and sent a representative to assist Chris in planning the event. We would rent out a large field at a local campsite, and bus in thousands of attendees. Several DJ booths were constructed at Amadou’s behest, and through some unnamed connection of his we rented several discounted Uhaul trucks, stuffed them full of alcohol and lumber, and built several mobile bars that could be set up and taken down with ease. It was, quite frankly, a stunning mobilization of manpower.

Later that week, Lori Berquam and the administration admitted that they had overstepped in canceling Mifflin, conceding that the move had only served to push the revelry underground. They agreed to bring back the storied block party the following year, and later cited the field trip as a model for how the university could work together with students to plan large events. “I think it really was an example that not every event in the Greek system trends toward chaos,” Chris told me recently.

At the time, a feeling of jubilation set in that lasted all week. Not only had we thrown the party of the year, but as we saw it, our shenanigans had saved a generations-old tradition for future classes.

So our elation was crushed that much more palpably when one one of the older members of Theta Chi called together a small group of brothers a few days later for an emergency meeting. I was not there for this gathering, but in the years since I have heard it described to me several times by those who were. And though the details have become warped with time, the rest of us at Theta Chi would all quickly become familiar with the general outline:

Amadou was heading the next day to New York, for the summer, to take a prestigious internship at J.P. Morgan—it was that rare cinematic dream-come-true moment, and one that should have been a cause for celebration for everyone in his orbit. Instead, for anyone entering The House that day, it must have looked as if the members of Theta Chi had seen a ghost.

There was a message on this person’s phone, several people told me, from a number nobody recognized.

This is some deep shit, the person said. What kind of shit?

This is bad, this is really bad, he continued, pacing around the room.

What’s bad?

So he set the cellphone down on a table, and the group went silent as the scratchy audio played faintly through the speakerphone.

“Hello, this is Special Agent ____ with the Drug Enforcement Administration. I’d like to have a conversation with you, about a friend of yours, Amadou Camara. Please give me a call back as soon as you can.”

***

Everyone has a story—the one friends and family implore you to share every time you meet someone new. It’s almost never complete, with missing details and characters that tend to shift over the years, though the truth is almost beside the point. For some it’s a past love; a brush with fame, a particularly robust accomplishment from their teenage years. Maybe an arrest accompanied by that lone, shameful night in jail; a bad job; a paranormal experience—everyone seems to be in possession of at least one good story.

Mine was never really mine at all, but rather Amadou’s, his determined rise and precipitous fall. It is, in my estimation, a uniquely American story—and though its subject lays no further claim to life in this country, his winding path to the precipice of global capitalism could have occurred nowhere else.

And despite the fact that this story belonged to someone else, I was nonetheless determined to put the pieces together in a way that made sense after all these years of rumor and intrigue.

Anyway, I figured the best place to start was at the beginning.

***

The Camara family is from a predominantly Muslim West African nation called The Gambia: a long, narrow strip of land surrounded on all sides by Senegal that hugs the River Gambia through its twists and turns for more than 200 miles inland.

At its widest point The Gambia is no more than thirty-one miles across. It’s Africa’s smallest country, and carries little strategic importance to world powers looking for the continent’s vast stores of natural resources and land. This fact has allowed it to largely avoid the extractive industries and some of the political maneuvering that has plagued other African nations, though it was colonized at different points by Portugal, France, and Britain.

Tourists, of which there are many today, have taken to calling it “the smiling coast,” perhaps the invention of some enterprising young marketing agent hoping to attract wealthy Americans and Europeans by dint of the country’s pristine white-sand beaches and relatively liberal market economy; or perhaps the phrase is a reference to the river’s wide mouth as it spills into the Atlantic Ocean.

Amadou’s father likes to tell his family story—I heard it at least twice when I went to visit him in Wisconsin this past summer. It begins with Amadou’s great-grandfather, Saikou Camara. Even in rural, pre-WWII colonial Gambia, he saw the value of an education and ventured abroad in search of one. Saikou left behind a young wife and family, and he planned on sending money to them whenever he could. But tragedy struck, and shortly after beginning his studies at a university in Senegal he fell ill and died.

Upon hearing this news, the story goes, his wife knelt down and prayed that his son, Amadou’s grandfather, Sambou, would inherit Saikou’s aspirations, and finish his dream of finding a better life for his family. As a teenager, Sambou enrolled in night school, became involved in his village’s political life, and eventually was nominated to serve in the country’s state assembly.

The country at the time was a protectorate of the British empire, though its ruling class was fighting, albeit more procedurally than violently, for its independence. It was a topic that would come to dominate The Gambia’s political discourse and define the lives of everyone involved—Amadou’s grandfather included.

This jump from the bottom of the country’s economic hierarchy to its political class meant that Amadou’s father, Habibou, and his siblings had been granted access to all the resources of an upwardly mobile Africa that had previously been out of reach for the family: Western education and property ownership, as well as things like loans and credit, which make such goals reachable.

Habibou would go on to attend the prestigious Gambia High School, in the capital city of Banjul. It was there that he would meet many of the country’s future leaders—though none more powerful, or more memorable, than Yaya Jammeh, the future Gambian president. Jammeh was a few years behind Habibou in school, but occupied space in his classmates’ memories as a uniquely competitive and somewhat spiteful character.

Following high school, Habibou went on to study medicine, and eventually specialized in toxicology. Following his residency, he occupied prominent posts at the World Health Organization and within the country’s health ministry, working to modernize the country’s medical infrastructure. Amadou and his sister were born during this time—and Habibou liked to say that their grandmother’s prayer had finally been answered.

But everything changed during the winter of 1994, when a military mutiny over a lack of pay for low-level army officers turned into a full-scale coup. Jammeh, then a twenty-nine-year-old lieutenant and one of the chief organizers of the original action, found himself elected leader of the “Armed Forces Provisional Council,” and head of the coalition that was now in charge of governing the country. “He was a cruel man; I remembered him well. He was vindictive,” Habibou told me, with a deep mercurial streak. Habibou remembered how you could be in good standing with him one day, and then later find yourself the subject of a deeply-held grudge.

Many of the government’s ministers fled the country almost immediately, fearing retribution for their loyalty to a previous administration, though Amadou’s father was committed to staying—his project of providing better medical care to the country’s citizens, after all, should have been a political winner regardless of regime.

But after Jammeh was formally elected as president of The Gambia in 1996, several prominent opposition leaders and former government ministers disappeared. Rumors of their torture and murder grew. A ruthless group of former military members called “the Junglers” were responsible for these killings, and a truth and reconciliation commission would later find that they were operating on orders from Jammeh himself.

So Habibou fled to the United States—landing in New York City’s John F. Kennedy Airport to start a new life. “I arrived at JFK with a lot of hope and $20 in my pocket,” Habibou would later write, “and not much else.”

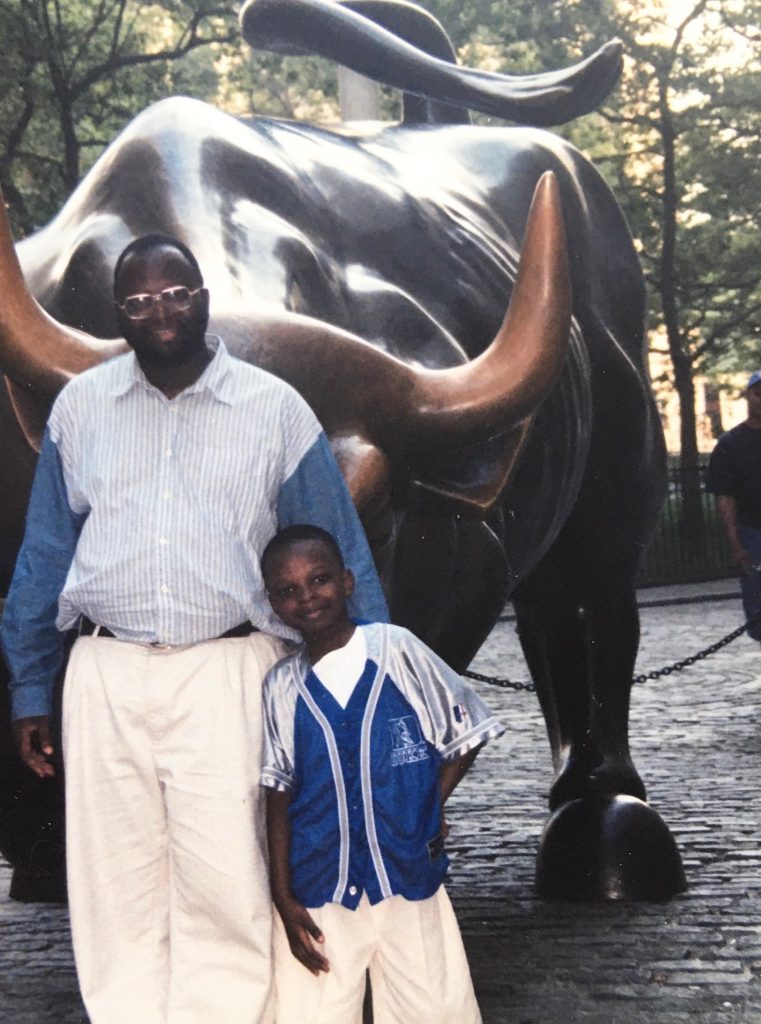

So he did the only thing he could do, given the situation: He started over. Habibou began working as a security guard at several buildings in the Financial District—more than an hour one-way commute from his new home in the Bronx. It might as well have been a trip to outer space, a different world, plunging Habibou into the center of global finance and then back again. For twelve hours a day, sometimes up to sixteen, he sat on the first floor of a number of buildings in lower Manhattan that housed the machinery of a global economy based on cheap credit and endless growth, and checked the credentials of capitalism’s foot soldiers. “I think that really affected him,” Amadou said. “He was really used to white collar work, having his own office.”

Still, Habibou had a front-row seat to what is commonly known as the “dot-com” boom, a period of then-unprecedented stock-market speculation and economic growth fueled by technology and, more specifically, investment in internet companies. Habibou knew this, certainly; The Wall Street Journal was delivered to his desk every morning and a bank of television monitors in the same lobby blasted Bloomberg and CNBC all day long. But he had a more visceral experience with the extreme wealth created during this period.

During those long days, and nights, Habibou would watch as men in thousand-dollar suits and watches that cost his yearly salary streamed past his desk, usually giving placid nods without making eye contact. He negotiated with drivers and the occasional police officer about the snaking line of jet-black BMWs and Mercedes idling on the narrow street outside, and even caught a glimpse of the helicopters sputtering to life on the roof, delivering the company’s executives from the Hamptons just in time for their morning meetings.

Through it all, he watched, and waited, and learned as much as he could. “I decided then that it was too late for me,” he said. “But I vowed then and there that my son would be a Wall Street executive someday.” It was, he conceded, his grandmother’s prayer, uttered all over again.

Habibou eventually saved up enough to buy safe passage for his wife and two children—four-year-old Amadou first and, a few years later, his eight-year-old older sister, Fatima—to join him in America. The family joined a growing Gambian expat community in the Bronx, poor but safe from the death squads that had become synonymous with their former home.

Habibou took Amadou to lower Manhattan often, and even had his son sit with him at the security guard desk from time to time. On his breaks, and after finishing shifts, they would wander around the Financial District: The two would stand outside the stock exchange, listening to the young traders debate the merits of various happy hour choices; they would walk past the World Trade Center, dodging throngs of tourists; and, when the weather was nice, Habibou and Amadou sat at Battery Park, at the southern tip of the island, and watch the boats stream in and out of the harbor. Everything, Habibou explained, is fueled by finance—the comings and goings of those boats, the movements of people around the city, of goods around the world, are all connected to those men in suits moving money around from the relative comfort of their offices—dozens of floors above where he sat every day.

“I didn’t really understand the details of how everything worked at that time—I was like, eight years old at the time,” Amadou recalled. “But I loved the fast pace of it, the money, the American-ness of it all. I definitely knew, ‘This is what I wanted to do.’

“At that age, it was definitely more about the money. I had such great parents, I wanted to take care of my family. I wanted to make sure we never wanted for anything again.”

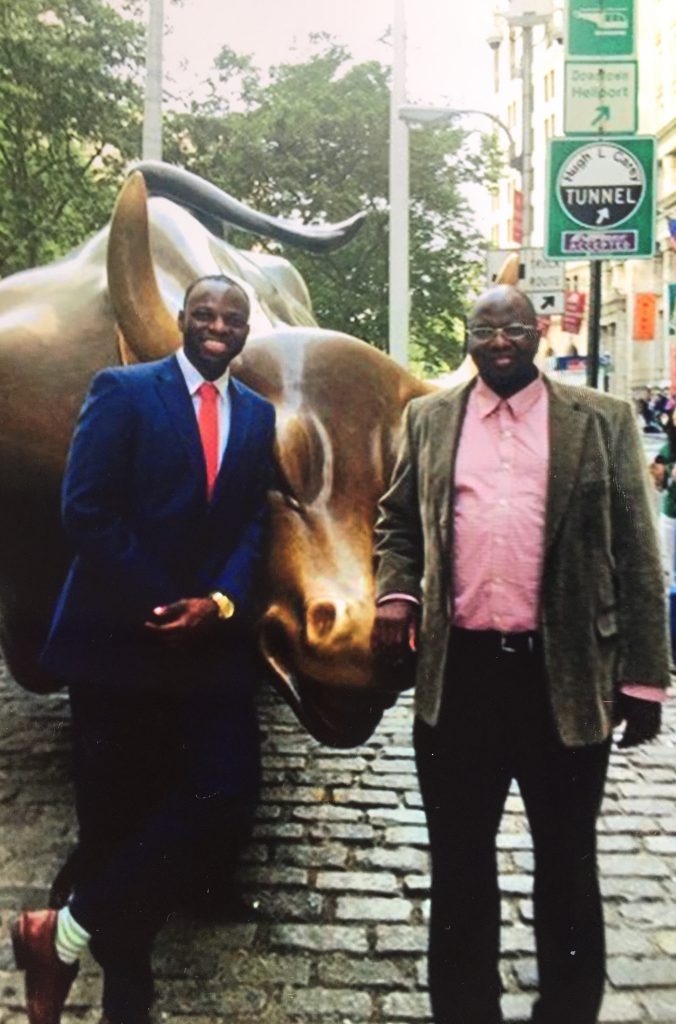

One day, at the famous Charging Bull statue, Habibou had his son pose for a picture. He later framed the image, and hung it in the family’s small, one-bedroom apartment—a constant reminder of the family’s goals and aspirations.

Nearly twenty years later, on the day Amadou started an internship next door at JP Morgan Chase, Habibou again posed his son and recreated the image, blinking through tears as the photo was snapped.

***

At the time of his arrival in the United States, Amadou had never left The Gambia, let alone seen the skyline of a global financial capital. The tallest buildings in Banjul are still three or four stories, the streets made of clay-colored dirt. The family, aside from Habibou, barely spoke English. “It was pure culture shock,” Amadou recalled. “Imagine what we looked like: walking around slowly, just staring up.”

It was a tough transition for the family, who were used to the relative comfort of their lives back in Africa. In The Gambia, “Families even in the middle class have maids and a personal staff, and we did too,” Amadou said. To lose that comfort, “It was tough for my parents, though they’d never show it. They’re strong people, they just pressed on.”

The family lived in a prewar brownstone off Gun Hill Road, a major thoroughfare in the Eastern Bronx that is today at the center of New York City’s large African immigrant community. The building was dirty, the entrance and hallways had gone years without being cleaned, and the elevators were constantly broken. It wasn’t uncommon to get stuck in one and have to be rescued by local firefighters.

But it wasn’t all bad, and like most children, Amadou was adaptable. Everything his family needed was within a few blocks, including other kids—many of them fellow African immigrants—who were quick to welcome the fast-talking Gambian into their midst. He watched at first, and later learned to play American sports like basketball and football. In the summer, neighborhood kids ran through the waterfalls created when their older brothers and sisters twisted open fire hydrants, as New York’s summer temperatures inched toward 100 degrees. Amadou explored the city, becoming adept at jumping over subway turnstiles when nobody was watching—one smooth motion, like a hurdler, and never look back.

The city was a playground. It had to be, for his parents were busy and couldn’t worry about where he was or what he was doing at every moment of every day. “I used to get in trouble a lot—nothing major, just little things,” Amadou said. “I think my parents worried about me, but there wasn’t much they could do.”

Then, when he was ten years old, his family moved to Wisconsin. Sun Prairie, to be exact. It was a shock.

Six years in the Bronx meant that Amadou had spent the majority of his life in the United States—but in a distinct, urban setting. He never really left the city. But now, “I remember flying in, and seeing rows of fields. I didn’t really register that it was corn until we were driving through it,” he said. “I was like, ‘where are the buildings?’”

The people in Sun Prairie dressed differently, acted and spoke in a new way. There were no trains and often no sidewalks, and everyone used a car to get around. It is, and was, the largest suburb ringing Madison—the state’s capital city, and home to just over 250,000 people—but it was still largely rural, and still largely white.

The one constant happened to be poverty. Though Amadou’s parents both had jobs, the reality of service work in post-recession America meant the family broke even, during a good month. The racial dynamics of their new home were also somewhat familiar—despite moving to a radically less diverse area of the country, the residents of his building, and his neighborhood in general, were mostly Black and Hispanic. But theirs was one of the only first-generation immigrant families, and they were some of the only people with noticeable accents. That caused a lot of problems for Amadou at first.

“The kids at school used to bully me a lot; they’d call me ‘pepper boy,’ he said. “Things like the food we ate was just different than what everyone else did. And the smells seeped into our clothes—I never noticed that before.” For many of the people living in Sun Prairie, he was also the first Muslim they’d come across. “Forget the kids, a lot of the parents had never met any Muslims before,” he said. Even things that might have seemed innocuous to the other party at the time, he still remembers as being a little rude. “Teachers used to ask me if I was Ramadan that day. You practice Ramadan. It’s a holy month, you know what I mean?”

***

When he got to high school, though, things got better. And the Amadou I knew in college made friends easily. He loved talking to people. He says that was always the case.

Amadou played football and ran track all through high school, and when those weren’t in session he played basketball and soccer with the rest of his classmates and other men in the neighborhood. The sports were fun, but they didn’t define Amadou in the way they do many other Midwestern teenagers. He didn’t have a car, and did have to work, which meant that he didn’t have much time for the parties and other activities that other students tended to occupy their time with.

Money was hard to come by, for most of the people in Amadou’s life. But there was always a group of young men in his neighborhood who seemed to wear designer clothes and drive fancy cars, despite the fact that they had no discernable jobs and lived in low-income housing.

One of them lived in the same building as Amadou and his family. He seemed nice, made sure Amadou was included in pick-up basketball games, and defended him when there was a dispute on the court. They always acknowledged each other when they crossed paths. Then, one day, as Amadou tells the story now, he got a little too close.

His family was living on the second floor of an apartment building off Bird Street, one of those prefabricated structures, easy and cheap to erect, that have become popular on the outskirts of American residential neighborhoods. One day Amadou, absentmindedly and entirely by accident, walked up an extra floor and found himself in the wrong unit—face to face with that man, a few women, several pounds of incredibly pungent marijuana, and a cash counting machine, whirring away despite the stunned silence of everyone present.

“I kept saying I’m sorry and slowly backed out of the room. My hands were up like he had a gun on me, I didn’t know what to do,” Amadou said. “I just thought, like, ‘Who’s weighing out drugs and keeps the door unlocked?’ It was ridiculous.”

About a week later, Amadou says, they ran into each other again at the neighborhood basketball court. Neither of them acknowledged the situation, and Amadou thought it would blow over. After the game, they found themselves walking in the same direction—perhaps by design, given what came next.

“He asked if I wanted to come on, if I wanted to work,” Amadou said. He figured he had two choices: Do it, and show that this man could trust him; or decline, and risk the consequences of angering a potentially dangerous criminal. Door No. 1 it was.

He could use the money, after all, and even back then had a mind for business. “I was always aware of the consequences, but I looked at it as a transaction. It wasn’t the nice cars, or the women, it was the sheer amount of money at stake,” he said. “It was the sound of that cash counter. I wanted that.”

So Amadou, sixteen at the time, went back up to the apartment he had accidentally entered the week before, and was fronted an ounce of weed to sell.

***

What came next, Amadou refers to as “hand-to-hand combat.” This was warfare, and failure was not an option. “I owed him a lot of money, plain and simple. I couldn’t afford to be robbed,” he said. “I knew I was in danger, but you can’t really think about that. I put the possibility in a box, and then I closed the box.”

Plus, he reassured himself, “weed was nothing, in the scheme of things. People were selling crack, speed, coke. A lot of heroin too.”

He would organize sales like this: When someone called, they would set up a meeting time. No explicit mentions of drugs. They would then convene somewhere in his building, if the other party lived there, or a parking lot a comfortable distance from prying eyes. Amadou would collect the money, and have the customer wait while he, or someone else, delivered the product. This is known as a “dead drop”—It was overly cautious, by small-volume suburban standards, but Amadou still says he’s proud of the fact that he’s never been robbed.

Amadou says he never really had a long term plan, at least not while selling that first package. Over time, he found that he was better at drug dealing than he thought he would be—though not without making mistakes along the way.

He was using the cell phone on his parents’ plan, which he quickly learned was a liability when it came to the police building an investigation, or even his friends and family finding out what he was doing. But he was a fast learner, and it was only a short time before he built up enough capital to buy in bulk, and wholesale to others in the neighborhood. Soon, he was buying several ounces at once, and was one of his suppliers’ best earners.

At the same time, he expended considerable effort to conceal his actions from the other people in his life. He had a rule against selling to his classmates at school, where he was still an honor roll student and a member of the Sun Prairie Scholarship Society, which existed to help low-income, minority, and immigrant students navigate the byzantine American college application process. “I wanted to keep it professional. I would never bring that kind of work home with me.”

This led to some funny situations. When I asked a mutual friend of ours who had gone to high school in Sun Prairie, he said Amadou seemed straight-laced, and always demurred when asked if he knew where to find the good weed that was floating around. “Sorry, I don’t know anyone,” Amadou would say. Then, knowing he was sitting on a couple ounces at any given moment, Amadou would accompany this friend on their quest. He admits now that these ventures would often end at one of his own street dealers’ homes. With a wink and a nod, Amadou’s dealers would always hand over the product, and accept the money without comment. Nobody wanted to admit what was really going on.

***

Perhaps most surprisingly, this went on for Amadou’s final two years of high school and none of it seemed to catch up with him. He attributes this to the fact that he maintained a relatively small operation that never conflicted with other dealers or drew the attention of authorities. Through it all, he never let his visions of Wall Street fade—or, perhaps more accurately, his father never let that dream stray too far from view.

Habibou pushed him to attend college in New York—Columbia and New York University were his first two choices—or, if that didn’t work out, another Ivy League school. But during the spring of his junior year of high school, Amadou finally came face-to-face with the reality of his life in the United States.

After getting a job offer at a restaurant in Sun Prairie, the owners asked him for a social security number—standard practice at most workplaces. He didn’t know it offhand, and asked his parents, who gave him a tax ID instead. Somewhere in the ensuing confusion, Amadou came to learn that he had arrived in the United States on a tourist visa, and that he was in the country illegally. Somewhere in the back of his head, Amadou says, he had the general knowledge that he wasn’t a citizen. “But nobody told me what that really meant up until that point,” Amadou said.

When he began applying to universities later that year, and the scholarships that represented a financial lifeline for a teenager from the Wrong Side of Town, he endured a series of phone calls and emails, one after the other, all with bad news. While he was a great candidate, with an incredible story, these schools would tell him, they couldn’t move forward with the application due to his immigration status. Of the public schools that would take him, there was only one real choice: the University of Wisconsin. It was a large state school with a good reputation—and more importantly—a prestigious business school. Best of all for Amadou, given the practical and financial constraints, it was no more than a twenty- to thirty-minute drive from his parents’ home.

Even then, it was clear that being undocumented would present a huge financial hurdle. This was before Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which Amadou would later qualify for, had been signed into law. Most scholarships and all financial aid at that time was contingent on one’s citizenship status. Still, he applied, and applied, and even seemed to get a few. But even then, things never seemed to work out.

Amadou remembers one encounter with a woman who asked to meet him on Bascom Hill, a lawn at the center of the University of Wisconsin campus. “It was August, and though we had talked on the phone about it for a minute before, she couldn’t stop crying,” Amadou recalled. “I was like, ‘What the hell is going on?’ She told me they had to pull a scholarship I had won.”

It was the summer before classes were set to start, and the scholarship was worth upwards of $20,000—more than a third of his parents’ annual income. “It was so close to classes, and I just remember thinking, ‘I can’t drop out now,’” Amadou said. “I just didn’t realize the extreme financial burden this was going to be.”

***

In another life, Amadou might have made a great journalist, or perhaps a detective. “Anyone can be good at talking,” Amadou said. “But I’ve always considered listening to be more important.” Though he was drawn to business, it was his ability to connect, to really get to know people, that they tend to remember.

He started a new habit near the end of high school: Upon entering every room he would force himself, oftentimes in contradiction of social norms, to shake hands with each person present. He was the Handshake Guy, and people remembered him for it. He also remembered what they had to say with a clarity that surprised whoever was on the receiving end of his shake.

On college move-in day, this ritual was repeated until others began to notice, and then comment on it. “I thought it was weird,” a friend of ours later told me, “But come that evening, he was the guy everyone knew.” And on that first, anxiety-inducing night at college—when you’re dropped in a new place, with new people, and the script for how you’re supposed to act has been shredded, most people latch onto the first thing that makes sense. And for many people, that was Amadou.

He chose that first year to live in Witte Hall, a large, ten-story mid-century dormitory tower meant to house as many students in as little space as possible. Nearly three generations of students have lived in the fifty-five–year-old building, which somewhere near the turn of the millenium had been given the nickname “shitty Witte,” an affectionate reference to the state of disrepair endured—perhaps preferred—by the Hall’s eighteen- and nineteen-year-old residents. It was at one of the dorm-room parties there that Amadou first met Montee Ball and Darius Feaster—at that point, two of UW’s most promising football prospects. At the time Montee was dating one of the girls who lived on Amadou’s floor in Witte Hall, and Darius was often with the pair. Later, Montee would set the NCAA record for career touchdowns, and Darius would become a reality television star as a contestant on “The Bachelorette.” Before any of that, the three of them became fast friends, texting each other nearly every day about parties, about girls, about the daily trials and triumphs of life as a student athlete or, in Amadou’s case, life as a first-generation immigrant.

It’s important to note, here, that perhaps for the first time in his life, Amadou was living in a predominantly white space. In 2020, after a decade of studies and initiatives and navel-gazing statements about racial fairness, the University of Wisconsin enrolled a Black student population of just 2.25 percent—well below both the state and national average population numbers. Perhaps as a result of their low numbers, there was a certain comradery among students of color that manifested itself in various daily interactions.

“I’d walk outside and see other Black dudes, we’d stop and talk to each other,” Amadou said. “Then later, when we were going out, I’d see them again, or they would see me across the street, and we would just converge into one big group.” One time early in Amadou’s first semester, he recalled, this amorphous group showed up at a party on Mifflin Street, one of the campus’s main residential stretches and thus a gathering place on nights and weekends. “So the door swings open and all these people see is a crowd of Black dudes.

“They wouldn’t let us in,” he said, a lengthy pause punctuating his typically rapid cadence. “I’ll never forget that feeling.”

The resulting friendships with other Black students were organic, hardened through daily indignities like this, and genuine in a way that everyone else noticed, even from a distance. It wasn’t long before Montee, Darius, and Amadou became household names on campus, recognizable to a wide cross-section of university social life. I remember the first time this group showed up to a party we had thrown, and the feeling of elation that came with it. You invited them to everything, out of an abundance of optimism, and when they showed up it lent you an aura of social legitimacy, of unimpeachable cool that would follow you around for days.

Amadou was, by extension, a highly sought-after recruit for many of the fraternities on campus. Though they were a little perplexed by his decision to remain sober at events where others went from cognizant to horizontal in the blink of an eye, he received a constant deluge of invites to events and parties. He learned quickly during that first week of school to turn his cell phone on silent mode, for fear of ruining another social interaction with a barrage of bells and whistles that indicated another message had arrived.

Thus, it was only after a sustained spring semester campaign that one of his high school friends, Brock, was able to convince Amadou to join a brand new chapter of a fraternity that he, along with another high school classmate of theirs, was starting: Theta Chi.

They had no house, no official recognition from the University and only a few other members, all of them white. Amadou politely said no, at first, but there was something he couldn’t shake, a feeling of missing out on something important. “It was almost laughable, but I just kept thinking that this was a blank canvas—and here was somebody handing me a brush,” Amadou said. “In the end, I wanted the opportunity to make a couple strokes.” He would end up officially joining the next semester, and in the meantime decided to live with the group in the fall.

At the same time as all of this was going on, Amadou was still working to stay current on his tuition payments, and largely falling short. Though he was still dealing here and there, without serious economies of scale earning the close to $18,000-a-semester cost of college was still a gargantuan task. A few days before January classes started, he was behind, and wasn’t able to enroll. “It really became a trend,” he said. “Classes would start before I had a chance to pay the bill, so I’d do the only thing I knew how—I’d go and finesse the professor.”

It worked this way: “By the time the classes I was eyeing started, it would be too late. So I learned how to formulate a preemptive strike.” The semester before, he’d visit the professors. “I’d go to office hours and get to know them, tell them how excited I was for their class. At some point I’d bring up my situation, and ask them to reserve a spot. Most of the time, it worked.”

Amadou learned, throughout that first year, to spend as little money as possible. He made bologna and white-bread sandwiches for lunch, cooked ramen noodles in the microwave for dinner, and made a habit of eating sardines or Spam on toast before going out to restaurants with friends. He joined trips to Costco, organized by other students with cars, which allowed Amadou to buy peanut butter and other things in bulk. His stomach often growled during class, but he pushed through, believing sincerely that better things were just on the horizon.

Something, he vowed, would change soon.

Part 2 will release with the Writerland newsletter on Friday, Feb. 11.