This Delacorte Review story is being published in partnership with London-based Granta magazine, with a mission “to discover and publish the best in new literary fiction, memoir, reportage, and poetry from around the world.”

- Boy, interrupted

Like every kid in Northern Uganda in the 1990s, Okello Moses Rubangangeyo grew up terrified of Joseph Kony. A mythic self-proclaimed messenger of the Holy Spirit, Kony was the brutal leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army, waging a vicious war against the central government.

Tales of terror wound their way into the children’s fantasies. So when Moses was jolted awake in his dormitory at school in Gulu one night in 1996, he couldn’t tell at first whether or not he was dreaming.

Moses saw men in dreadlocks striding among the beds, and “When they shook their heads like this,” he told me, standing up and shaking his head fiercely to demonstrate, “drops of water sprinkled on you.” The rebels were carrying flashlights, and as the light beams penetrated the droplets they created an effect like that of a prism on the walls of the room.

What is that? Moses asked himself. Is this a rebel thing? Or is this magic?

‘Get up! Getup, you stupid!’ the rebels muttered furiously. ‘There is a war going on outside!’

Moses was terrified. It was not magic.

*

I first met Moses on a sweltering afternoon of March 2014 in Gulu, Northern Uganda, which was the stronghold of the Lord’s Resistance Army during the civil war. I had travelled to the region to cover the massive influx of refugees caused by yet another brutal war, in neighboring South Sudan. Matthew Green, a former Eastern Africa correspondent for Reuters and one of a few journalists to have met Kony, suggested I talk to Moses, who had guided him in his quest for the feared LRA leader—a journey he chronicles in The Wizard of the Nile, published in 2008

Moses agreed. He wore a buttoned-up blue shirt, light brown pants, and socks and shoes, even though the thermometer was at 87 degrees Fahrenheit. His outfit had been carefully chosen. If people on the streets saw the many scars in his body, he explained, they would recognize him as a former LRA soldier.

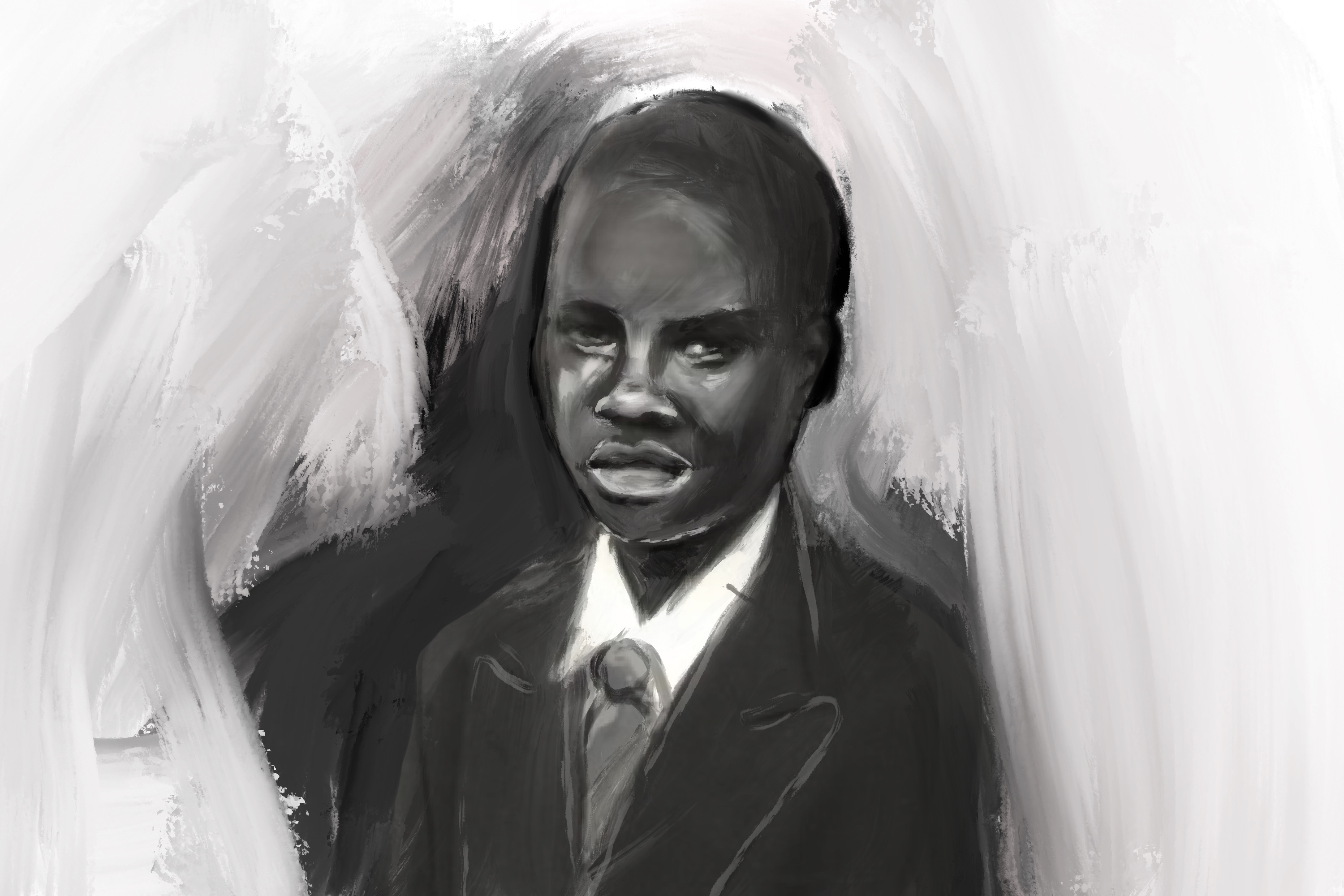

Moses had a shaved head and this, together with a thin, patchy moustache on his oval face, gave him the appearance of a teenage boy—the schoolboy he once was—in the body of a fatigued man.

He is now in his early thirties, the caring father of six, and the killer of an uncertain number of “enemies.” He is a loving husband and the former keeper of two kidnapped young women, one of whom became pregnant with his second child while in captivity. Like thousands of boys in Northern Uganda, Moses was abducted by Kony’s LRA rebel army at a young age—he was sixteen—forced into military training, and turned into a child soldier.

Over a period of eight years living in the bush and fighting with the guerrillas, he rose through the ranks of the LRA until he himself commanded thirty-four abducted boys he kept as child soldiers.

This cycle of violence repeated itself for three decades after the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Auma “Lakwena” (“messenger,” in Acholi), a self-proclaimed prophetess, started waging war against the Ugandan president, Yoweri Museveni. In 1987, when Alice fled into exile, Kony inherited her role and built the movement into the Lord’s Resistance Army, Central Africa’s most feared rebel group. It was as recently as 2017 that the United States announced the end of an $800 million manhunt for Kony, a program that had lasted for six years but failed to capture him.

Only one LRA commander has ever been brought before the International Criminal Court at The Hague: a man named Dominic Ongwen, who faces seventy charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Like Moses, he was kidnapped as a schoolboy (he had been fourteen) and turned into a child soldier. This spring, the closing statements in the case started this March, 2020. The judges will then have ten months to issue a verdict: victim or criminal?

That same question has haunted me since the afternoon that Moses and I sat to talk inside a blue-plastic tent in the backyard of a guesthouse in Gulu.

As we sat in tottering plastic chairs, Moses took a tiny notebook out of his pocket, and placed it on the table in front of us. In it was the diary he had kept during his last years in the bush. He was also carrying a book: Tall Grass: Stories of Suffering and Peace in Northern Uganda, written by Father Carlos Rodríguez, a Catholic missionary who served in the area through the war, and who had influenced Moses’ escape from the LRA.

Moses wanted to take me back to his years with the LRA. A decade since his escape, he was still trapped in his past, struggling to move on. So for the next four hours, Moses performed what was almost a monologue—an extraordinary tale of aberrant truth—about his journey since the day of his abduction, when the rebels came to his school.

At times, Moses’s testimony sounded to me like a confession in the sacrament of Reconciliation. It was as if he was seeking something. Something like absolution.

*

Samuel Baker Secondary School opened in 1953, and over the decades the all-boys institution established a reputation as one of the best in Uganda, known for bringing forth thinkers—ministers, ambassadors, judges, professors. When Idi Amin took power in a coup d’état in 1971, there came a period of conflicts, economic neglect, oppression, and atrocities against Northern Ugandans by successive ruthless leaders. All of this fueled the emergence of rebel groups like the LRA.

Just 7.6 kilometers from Gulu, the region’s largest town and the heart of Acholiland—home to more than one million Acholi people, an ethno-linguistic minority group—the Sir Samuel Baker campus was surrounded by conflict and began to decline. But dedicated schoolboys like Moses still tried to live up to the expectations placed on the students of the golden generations.

That all ended for Moses the night the rebels came.

Get up, get up! Moses still remembered their voices, the way they shook the beds. “We are suffering in the bushes and you are sleeping here? – you lazy stupid kids!”

During the war, students and teachers did not leave the school campus for months. They lived in five dormitories, with eight double-decker bunk beds in each. The facility was supposed to be guarded by the Ugandan Army, but that night the soldiers were nowhere to be seen. Still, the rebels moved carefully, fearing that a neighbor might alert the military detachment that was positioned just a kilometer away.

The boys were tied together with a rope at the waist in groups of five, and within a few minutes they and the rebels had vanished into the bush. Forty stumbling schoolboys were taken that night, including Moses and his two half brothers.

Moses tried to note the directions they were heading: Okay, we are following east. Now north. Ok, northeast. No, not east, south. Oh, are we going back south? They seemed to be walking in circles, but in the dark in the bush it was hard to tell. He only realized they were not walking in circles when they arrived at a forest clearing, where a smell of burning lingered in the air.

They boys were led inside a straw hut. There a man—Moses later learned he was an LRA commander named Mariano Lagira Ocaya—sat in front of a radio transmitter. “He looked very ugly. Very, very ugly, with a sad, gloomy face,” Moses said, grimacing. ‘He spoke like someone who is not human. And he never smiled.” Rebels holding walkie-talkies and rifles searched the abductees’ pockets for money, IDs, or whatever else they might be carrying, then lined them up before the commander.

“Do you know me?” Moses remembers Lagira asking.

“No, sir, no,” the terrorized boys responded, wondering whether or not this was the right answer.

“Do you know anyone here?”

“We don’t know anyone, sir,” the boys lied. Moses tried to avoid eye contact with his schoolmates and brothers.

“Where are you from?”

“From school, sir.”

The commander turned to Moses: “You! Why were you at school?” Moses was trembling. “Sir, we don’t know. It was our parents who took us to school.”

The commander asked what he was studying, but Moses was too nervous to reply. His mind went blank. Sir Samuel Baker School already felt distant.

“Do you think you are cleverer than me?”

“No sir, I am not, I am not.”

‘Why did you go to school instead of joining us here so that we could fight the dictators in the government? You, stupid Acholi!’ the commander shouted.

A ray of hope lightened the boys’ spirits when the commander recognized one of them. “He introduced him as the son of a brother. If they are relatives, maybe we’ll be released,” Moses thought. But instead the commander ordered the boy to lie down, and then made a sign to four armed men in the hut.

They came with large clubs. “They beat that young boy seriously,” Moses said. Sixty strikes, from each of the four rebels.

Moses soon learned that the beating was part of the LRA’s “registration” process, when new abductees had their names “written” on their own skin – “Not with a pen, but with big, big sticks,” Moses said. Moses spelled out his own name for me, reproducing the noise of each strike in between the letters, just as it happened then, writhing as if he could still feel the pain. “They beat you with full strength,” he said. “They were called the ‘fire brigade’.”

Those who were seventeen and older (the eldest was twenty) had to stand during the “registration.” “They call it waiting for a bath,” Moses said, bending over to show the position. It was meant to be a funny name, but only the rebels were laughing.

The children were supposed to show no emotion. Crying could cost them their lives. “They put you at gunpoint, and you are not allowed to make any sound,” Moses said. “The first twenty strikes you believe you won’t survive the pain. But then you stop feeling it.”

To stop feeling was precisely the point. This was a strategy developed by the LRA, and described by Moses as intended “to remove the civilian life and school ideology from you, and transition you to the military.”

The beatings lasted for three days, after which the boys felt crushed, their bodies battered and swollen. The “registration” dehumanized the recruits, but was also a tool of natural selection. Only the strong endured.

The survivors were separated into battalions under the command of the LRA’s four brigades: Gilva, Sinia, Stockree and Trinkle. Moses and his brother Francis were assigned to Stockree brigade, but put in separate battalions. His other brother, Baptist, was part of a group immediately taken to one of the LRA bases in Sudan. They never saw each other again.

*

The abductees mainly performed heavy-duty work. They carried supplies to the rebels—food, water, ammunition. And they soon learned to never, under any circumstances, even when asked, say they were tired or needed to rest. In the rebel’s language that meant “to die.”

Beatings were frequent, and any misstep could be fatal. “It went on until most of us realized that the only way to stop that was if we changed our attitudes,” Moses said. “So, you pretend to be sharp.”

This was the beginning of Moses’s transformation.

Soon the boys began receiving military training: “assembling and dissembling a gun, firing, marching,” Moses said. For some time abductees carried wooden logs, chosen to be the size of a Kalashnikov, so they’d get used to the weight. Only after getting a real gun would they become a soldier and no longer be beaten, Moses was told. “So we started craving for a gun,” he said. The boys would never be given one. They had to earn it. And the way to earn a real gun was to take one from the dead body of a Ugandan soldier.

Two months after Moses’s abduction, Stockree brigade left on a mission to Aboke, in the neighboring Kole district, south of Acholiland. On their way, Moses’s battalion was caught in an ambush. It was his first experience in crossfire. But all he could think of was that he had to earn a gun. “When we saw ourselves in an ambush . . . trtrtrtrtrtr,” Moses said, reproducing the noise of a machine gun and bending down as if bullets were again flying over his head. “We couldn’t do anything with a log. So, our strategy was to hide and look for dead soldiers.”

Moses quickly found one. “The uniform was stained with blood. I had to pull it off,” Moses said, repeating the movement. An expression of disgust filled his face as he did so. “I removed his boots, the gun belt . . .”

Moses then put the gun on his shoulder and waited. He had no intention of using it.

*

From the moment of his abduction Moses carefully observed the rebel’s movements, and nurtured plans to escape. But he could not see a way out. “Let me tell you, because many ask me why I didn’t escape earlier—I call it a silly question,” Moses said. ‘When you are in the bush for a week, you don’t know the security. You can escape. But can you survive?” He looked at me as if he was still seeking an answer.

At first Moses thought that it might be possible to escape if he had a gun. And then he had one. “But after one or two months, you will know all the tactics of security and defense. You will know that there is an observation patrol over that tree, and that one, and that too,” Moses said, pointing into the air. “You will know that, at night, at least ten patrols block this road, and that, and that one too, everywhere around.”

“And they trick you,” Moses continued. “Once you acquire your gun, they will test you. They will send you out alone into the bushes on a mission”—to fetch water, for example—“but you know there is always someone following you secretly, someone up on a tree observing your movements. So you don’t risk.” Those who dared were killed in front of all the others.

And that’s not all. One LRA tactic to prevent abductees from escaping was to beat them all for the misdeeds of one. Another was to randomly pick an innocent boy and force the others to beat him to death. “That made us keep an eye on each other,” Moses said.

The new abductees were kept “under heavy security” until they gained the trust of the commanders.

By then, they were complicit. They were LRA.

*

Shortly after Moses acquired his gun, the battalion went on with the mission. “Around 1 a.m., we reached Aboke,” Moses said. The rebels scanned the area surrounding the village to make sure government soldiers were nowhere to be seen.

The target was St Mary’s College, a Catholic school for girls. The recruits were ordered to guard the gate outside while senior rebels went on with the mission, Moses said.

It was October 9, 1996: Ugandan Independence Day. Inside the gates at the school, rumors had begun circulating that the LRA was preparing an attack. By then, the group’s many atrocities were well known. Those included mutilations, summary executions, and sexual enslavement—young girls were often abducted and given away as “wives” to the commanders.

The LRA was at its peak. Their forces numbered in the thousands and the army seemed overwhelmed. When the students and nuns went to bed that evening, the government’s promise to send a few men to protect the school was yet to be met.

As described in Stolen Angels: The Kidnapped Girls Of Uganda, at around 2:15 a.m. the college gatekeeper knocked on the door of Sister Rachele Fassera, the school’s deputy headmistress: ‘Sister, the rebels are here.’ The men had broken into the school through the back gate and moved into the students’ dormitories. They left just before dawn, taking 139 girls from thirteen to sixteen years old with them.

Moses remembers marching for hours afterward when, all of a sudden, Sister Rachele and a young teacher named John Bosco Ocen emerged from the bush in front of the group. As the two stared at the Kalashnikovs pointing at them, a Ugandan helicopter surged into the sky and bullets started to fly.

The group kept marching for another four hours, walking and hiding until the Ugandan military lost sight of them. They reached one of the LRA’s camps, where several hundred other rebels were also gathered.

Sister Rachele pleaded with the commander to let the girls go. Perhaps because she was a nun, and the LRA was allegedly fighting to establish a Ten Commandments-based theocracy in Northern Uganda, Sister Rachele eventually persuaded him to release 109 of them. But, the thirty youngest girls—for they had a better chance to be virgins and free of HIV—remained with the rebels. They were all to be handed over to Kony.

According to Moses, one girl secretly told the visitors where the students from Aboke were being kept. “The other girls were made to kill her, after they left,” Moses said. His eyes looked wild, haunted, as he remembered this.

Five of the girls abducted from Aboke never returned home.

*

On the way back from Aboke, the rebels set up camp to rest and eat. Moses had been assigned to cook for his battalion, and the commander called him over.

‘Rubangangeyo, come!’

Moses interrupted his story here to tell me how annoyed he felt that the recruits had to address the commanders as “japwonj,” which translates as “teacher” in Acholi. “It was funny,” Moses said, though he wasn’t laughing. “I was used to educated teachers, real professors. Now I had to respond to these illiterate men.”

“Yes, japwonj?” he answered, hiding his discontent.

As he recalled what happened next, Moses cringed; his whole body shivered. “I was a very good cook, so I thought he’d ask me to cook for him.” Instead, the commander gave Moses an order he couldn’t have anticipated.

“Go and cut off that man’s legs!”

The rebels handed a small axe to Moses.

By then it was forbidden to ride a bicycle, Moses explained, because it would be easy to go and report the rebels’ location, and the soldiers could respond quickly. So the LRA had been warning villagers not to ride bicycles.

“They caught that stubborn man riding that bicycle. He was a big man, thirty-five maybe. They laid him down there . . .” The punishment was to chop his legs off, “so he couldn’t ride his bicycle again.” Moses had been “selected” for this task.

“I was forced to . . . I was forced to do it,” he told me, avoiding eye contact.

The commander noticed that Moses was “a bit dodgy” about this task. “They hit me with the gun in the head. So, on order, I started . . .”

In front of me, Moses repeated the movements he had made that day, cutting the air with his arms as if swinging the small axe. “It took me several times, ten times, argh! I was feeling so bad!” he said. “They should have given me the big axe. You know, those used to cut firewood.”

Moses interrupted his narration again, taking a piece of paper and drawing a small axe on it. “These can’t cut anything. Women dance with it.” Then, he drew a bigger one. “This one is heavy. You can do it at once and forget it. But, with the small one, it took about ten times to cut off . . . with blood splashing on you, with the fat splashing on you . . .” His face contorted with distress as he described the scene. “It was so painful to me. But I did it.

“On orders, I did.”

As Moses descended back into hell, and the hell imposed upon others, he alternated between narrators—the schoolboy, the child soldier, the commander. My own feelings alternated too: from empathy, in the moments I could see the schoolboy he once was, to deep sorrow, as I thought of the victims of all this horror. I also felt anger. How could the international powers have allowed such atrocities to persist for so long?

Moses elevated his head and took a deep breath. He looked tortured, as if emerging from a waterboarding session. But his memories soon pulled us to the next ambush his battalion was caught in. This time, Moses fought back.

When the battle ceased, the rebels were happy. “Because it was an ambush from UPDF!”—the Uganda People’s Defense Force, meaning the Ugandan Army. Moses no longer looked at me as he spoke. Instead, he stared into space. It was as if he was still in the bush, carrying that gun again.

“We defeated them!” Moses said, with a long laugh. “Actually, let me say, we defeated them!”

I couldn’t help but notice that this was the first time during our conversation Moses had used the pronoun “we” while referring to the LRA.

The recruits were greatly relieved after that fight, because about half a dozen of them got guns. “There would be no more serious beatings,” Moses said. “And, you know? You start becoming used to things, because there is no way you can escape.”

For the next eight years, Moses lived in the bush, mostly in Sudan, with almost no contact with civilian life.

“So,” he said, “I became a soldier.”

*

- God knows

Moses was taken to southern Sudan four months after his abduction. At the camp, he joined thousands of fighters and newly abducted boys and girls. The camp was the largest of the many LRA camps that were established in the area during the late 1990s. It served as a training camp as well as the group’s main headquarters—and it was home to Joseph Kony.

One Sunday morning, the new recruits—boys and girls—were gathered around a big mango tree. This was just two weeks before Christmas, and Moses loved Christmas, when his family would gather around a decorated tree and share traditional dishes.

A man wearing a light brown suit and a robe appeared before the children. “You are most welcome to Sudan,” the man begun. “You are the new Acholi. We’ve liberated you from the dictators of the Museveni government.”

The mysterious man was holding a Bible. He opened it, as Moses remembers, to a verse from Matthew 5:30: And if your right hand causes you to stumble, cut it off and throw it away. It is better for you to lose one part of your body than for your whole body to go into hell.

“It is in the Bible! That’s why we are chopping people’s hands; they are doing bad things with them. If they can’t listen to us, we chop off their ears. And if their mouths talk something bitter, you better cut it off too.”

The man also used the Old Testament to justify the LRA’s enslavement of women. “You can take as many as you can keep, like King David. It is in the Bible!” he said. “And Kony can keep 200 women.”

The man moved to Sodom and Gomorrah, the sinful cities destroyed in Genesis 19:24. “God killed people because He got angry,” Moses remembers the man saying. “If anyone disobeys you, kill him! Those who obey you, bring them closer! It is God’s words.”

“God is a soldier!” the man concluded. “Kony is a soldier!”

Moses only later learned that the man preaching was Kony himself. “I never imagined,” Moses said. “The way he was talking . . . He was a very gentle man, actually. Very gentle.”

That Sunday the brutal leader of the LRA made the children feel special: “You obeyed to Kony, and that’s why you are here. You’ve survived. You are the new Acholi!” he told them. “We are going to kill all the stupid in Uganda. They say Kony is bad, but Kony is not bad. If Kony asks the local council to give fifty young boys and girls to join us, will they accept that? No. So, the only option is to take you. But we are not kidnapping anyone. We are uniting our brothers and sisters.”

“Have we abducted anyone among you here?” the leader asked the crowd.

“No, no, no sir!” the terrified boys and girls responded.

“Is Kony bad?”

“No, no, no, no sir.”

“Are you happy?”

The boys and girls lied again. “Yes, yes, yes, yes.”

“Are you happy to join the new Acholi?”

“Yes,” they repeated loudly, making sure their voices were heard: “Yes, sir!”

“Those were silly answers,” Moses told me. “We were pretending. We couldn’t even feel our legs. We had walked for three weeks, and thousands of miles, seeing people die on the way.”

After the sermon that Sunday, the newly abducted boys and girls were “baptized”—their naked chests, backs, and arms marked with a cross, using a mixture of white clay and water. They were anointed with “holy oil” made of Areca palm nuts, poured on their forehead and parts of their body. During the ceremony they were asked to confess their sins. If they refused, they were told they would die soon. If they confessed, they’d become invisible to “enemies” and no bullets would ever reach them.

“They were indoctrinating us, brainwashing our minds!” Moses said. “You start thinking that maybe the polygamy, the killings or even chopping . . . might be connected to something spiritual.”

But such thoughts wouldn’t last. Later that day, Moses learned that his brother, Baptist, had been beaten to death. His other brother, Francis, also had died, possibly “from cholera and hunger.”

Their bodies were never found. “Those who were a bit stronger,” Moses said, “we got used to life in the bush.’

The surviving recruits were required to attend Kony’s sermons twice a week, on Fridays and Sundays. “He could preach for six hours, standing. So we all had the chance to see Kony,” Moses said. But if there was any part of Moses that, even for a moment, wanted to believe in Kony’s spiritual powers, that part died with his brothers.

*

Joseph Kony was one of seventeen children of a catechist father. He grew up in Odek, a sub-county of Gulu district, raiding cattle and attending Catholic services. At a young age he became a traditional healer, or “witch doctor,” attending to the community from his family hut until he left with a number of followers to fight against Museveni’s government.

Musevini, an ethnic Munyankole, took power in Uganda in 1986, after a rebellious campaign that overthrew Idi Amin and the brief Acholi-led military government of General Tito Moses. Northern soldiers either defected or were discharged. Back home in their villages, they organized several resistance groups to fight against the National Resistance Army led by Musevini. They counted heavily on popular support from local Acholis, as well as on spiritual guidance. It was in this context that the self-proclaimed prophetess Alice Auma came to prominence.

Neglected in the real world, the Acholi blamed evil spirits and witchcraft for their misfortune and illness, and relied on traditional healers to scare them away. As anthropologist Tim Allen of the London School of Economics and Political Science wrote, “Spirit mediums helped to establish a degree of social accountability in a world where the state had largely lost its credibility and collapsed, and where witchcraft and sorcery were widely believed to be the most common causes of mortality.”

Traditional beliefs, old grievances and new forms of violence and oppression by Museveni all nurtured the growth of the movement. And marching semi-naked, with ash crosses drawn in their bodies, Alice’s followers managed to scare Museveni’s army away from Northern Uganda. This success helped attract more followers to the movement. By 1987 the Holy Spirit Movement was believed to have as many as 8,000 fighters, but the group was defeated after crossing into the Museveni-controlled south. Alice fled to Kenya (she died in 2007), and was replaced by Kony.

As the group’s brutal tactics and mass atrocities—mostly against its own Acholi people—became known, Kony lost credibility and his popular support evaporated.

This is what led him to adopt new strategies to grow the ranks of the LRA: massive abductions of young boys, who would be turned into soldiers, and of girls, who would bear their children.

*

Moses learned that the more senior the officer in the LRA ranks, the better the food and treatment. Officers were spared from heavy work, and enjoyed relative comfort and perks, such as having a ting-ting (maid) and being allowed to choose a “wife,” or several.

Major General Kony lived with many “wives,” including Lily Atong, sister of Dominic Ongwen, the commander who is now on trial at the International Criminal Court in The Hague. She gave birth to six children with Kony. The LRA leader is said to have fathered as many as fifty with girls and women in captivity, though the exact number remains uncertain.

The LRA had a well-established and controlled structure, according to reports by the NGO Enough Project. Camps were organized in several parallel circles. Senior officers resided in the inner circles, protected from all sides by indoctrinated fighters. Kony stayed in the center, surrounded by a personal escort.

Kony appointed those who were granted higher status in the hierarchy; his commanders had to get his blessing before promoting their own subordinates. The perks and the recognition motivated younger fighters like Moses to show more loyalty, discipline, and bravery in conflict.

The LRA chain of command followed a line of authority similar to that of the Ugandan army, but with a few tweaks: “They’d give you boys and women to be under your command,” Moses said. “And this became your unity. But not like in the government. They called it your family.”

Moses was promoted to sergeant, the initial step up in the chain of command, and later to battalion administrative officer and brigade administrative officer. Moses grew closer to the group’s leadership—or the “Control Altar.”

As an administrative officer for the Stockree Brigade, Moses counted the dead; the sick; the disappeared; the fighters in combat and those on standby; the women; and the children, both the abducted and those born in the bushes. He knew the LRA’s positions in Uganda and Sudan, and the moves they were planning. “I knew everyone of the 1,500 people in the Stockree Brigade by heart.”

At times, Kony called the brigade administrative officers together for a meeting. “There were just four of us, and the chief administrative officer and his second in command. So, he came to know us,” Moses said, with a smile that looked like pride. “Also, I was a very good administrative officer, because I was a bit educated, uh? So Kony knew me personally.”

But it was a harmless skill that brought Moses closest to Kony. “I was also a tailor, and this skill gave me a lot,” he said. “Kony would invite me to his place to sew his wives’ dresses.”

I asked Moses if he came to like Kony. Moses remained silent for a while, and his answer, when it came, was reluctant. “Yes, sometimes . . . because the stories we heard were different from what we saw. It was rare to hear him give an order to kill. But it was common to see him quarrel with his commanders-in-chief who gave such orders. So I wondered if those illiterate commanders were the bad ones.” (Several reports contradict this, affirming that Kony did give orders to kill, including those who disobeyed him.)

In times of peace, Kony would come “say hello.” The feared chairman of the LRA would call Moses “writer,” for he was one of the few among the LRA who had a good education. “Hey, writer, how are you? Thank you very much, writer!” Moses says, mimicking Kony’s voice. “Those were his kind of words.”

“Also my name, Rubangangeyo, amused him a lot,” Moses added. “It means ‘God knows’.”

*

Life at the LRA headquarter camp in Sudan was not easy, but it was better than hiding in the bush in Uganda. In Sudan, the rebels didn’t need to raid villages for food as often—basic supplies as well as arms were provided by the Sudanese government. Sudan President Omar Al-Bashir had adopted the LRA as a proxy in retaliation against his rival, Museveni, who was supporting rebel groups that were fighting for the independence of the Christian-majority southern part of Sudan from the Muslim North. (South Sudan would eventually gain its independence, but not until 2011).

LRA soldiers shared bases with Sudan’s Army and received military training derived from “British tactics from the 1960s and early 1970s, with an emphasis on anti-ambush drills and jungle fighting,” according to reports by the Small Arms Survey.

On Fridays, the day of worship for Muslims, Sudanese Arab fighters joined the LRA for prayers. According to Moses, Kony would adapt his sermons in what he describes as “a kind of mixed, hybrid religion,” combining Christianity, Islam, and traditionalism.

Under the protection of Sudan, the group enjoyed years of relative stability. This allowed the LRA rebels, or at least those allocated in the brigades’ headquarter camps, to build an infrastructure similar to that of the rural communities in the region.

After he became a sergeant, Moses was allowed to have a “wife”: a sixteen-year old girl abducted from Uganda, who was chosen for him by his direct commander. Once a girl was given to an officer, he had to accept her, and no one in the group was allowed to touch her. “She was too young,” Moses said, “but they forced me.” When he climbed further in the ranks of the LRA and gained a little bit more freedom, Moses gained permission to choose another girl. The one he chose had been taken by the group during a raid in Northern Uganda. “She was eighteen. That was a fit for me.”

At the camp in Sudan, Moses’s “wives” spent their time doing things like cooking, laundry, fetching water. They helped others to give birth, and to raise the children.

The experiences of LRA-enslaved ‘wives’ vary, often depending on the status of their husbands. They invariably involve horrific physical and emotional torture, and rape. But there are also tales of survival. Amid the violence and horror they suffered and witnessed, everyday life superimposed itself. The rebels were often abductees who had been taken away from their families as children, just like the girls, and it was not rare that they would bond over time. Others deliberately forged such bonds as a way of coping, of carrying on with their lives while still in captivity.

Eventually Moses was allowed to have his own “children”—child soldiers, just like him. “They’d give you ten children, and that became your unity. In periods of abductions you could increase that number, depending on how well you could keep them. I had thirty-four,” he said. “They became the children of Rubangangeyo. You are responsible for them.”

Moses described how he repeated, at least partially, the cycle of violence imposed upon him, beginning with the “registration” into the group. “I can’t even regret, because the same thing happened to me,” Moses said. “It’s like bullying in school. You are mistreated, and when the next group comes in you are supposed to mistreat them.”

Hierarchy was taken seriously in the Lord’s Resistance Army. None of the fighters were allowed to loot or abduct or kill without the consent of their immediate superior. Moses said he “specialized” in the big ones, sixteen to nineteen years old, “because, in case you are wounded in a battle, they can carry you.”

But there was another reason too: “The big ones know how to separate what is good and what is bad,” he said. “Those who are fourteen, fifteen years old—they simply kill, annoyingly, even without order. They can do bad things.” Most commanders, according to Moses, refused to keep the older boys, because “they know better, and they tend to escape.”

But, with time, Moses learned something: “I learned that if you treat them well, they stay.”

*

Moses rose through the ranks of the Lord’s Resistance Army in a time of renewed fighting. In December 2001, the George W. Bush administration had included the LRA on its list of terrorist groups. The designation wasn’t exactly meant as a way of directly targeting the rebels, but rather as a way of applying pressure to the Sudanese President Bashir, who, in addition to adopting the LRA, had also hosted Osama bin Laden in the 1990s, a decision that attracted American sanctions and cruise missiles.

The US war on terror indirectly provided new fuel to the conflicts in Uganda. Pressured by Washington, Bashir signed an agreement in 2002 that allowed US-backed Ugandan Forces to enter Sudan to hunt for Kony. “Operation Iron Fist” was launched in March 2002, and inaugurated one of the bloodiest periods of the war. The Ugandan military raided and destroyed several LRA camps in the Sudanese province of Eastern Equatorial, but Kony and the group’s top commanders managed to elude capture, fleeing to the mountains at the border, where they continued waging war against Museveni.

In retaliation for Uganda’s military offensive, Kony ordered his rebels to return to their old battlefields in Northern Uganda with full force. The group conducted dozens of attacks and ambushes in the Gulu, Kitgum and Pader districts.

By then, the government had forced the population to relocate to “protected camps.” Residents often lived in appalling conditions, and they were anything but protected.

Rebels raided the camps, looted villages, burned homes and disrupted humanitarian aid. Abductions increased dramatically, with thousands of children enslaved and forcibly conscripted into the LRA’s ragged army. Brutalized recruits terrorized, raped, tortured, and killed scores of civilians, leaving behind traumatized people, orphans, and a trail of corpses.

Amid this extreme violence, local clergy organized around the Acholi Religious Leaders Peace Initiative, and travelled to Kampala to try to persuade President Museveni to give them permission to initiate contact with the rebels. He agreed. A landmark meeting was held on July 14, 2002 with the clergy and the LRA’s most senior members, including Kony’s second in command, Vincent Otti. In the following months, religious leaders ventured into the bushes unescorted at least twenty times, delivering secret letters from the rebels to Museveni, and vice-versa, in an effort to bring both sides to the negotiation table.

On March 4, 2003 Moses was sent to one of these meetings, along with other LRA commanders. He helped to receive the delegation and to arrange for them to talk to Kony via radio. As Moses followed Kony’s broken conversation with the delegates, he found himself distracted. “I was thinking, like deeply thinking: What kind of war am I fighting? What is the agenda? Might this be a senseless war?” He asked himself, in silence: Do I want to die in captivity?

For seven years, Moses had been assigned to the LRA headquarters in Sudan. Being back in Northern Uganda changed something in him. He started thinking about his family again. He also realized that, of the boys abducted from Sir Samuel Baker School with him and taken to Sudan, he was the only one still alive. It dawned on him that “all of the others had died in the battlefield,” he told me.

Just before the delegation prepared to leave, he managed to discreetly whisper something to Father Carlos Rodríguez, one of the Catholic missionaries present in the talks: “Tell mom I am alive.”

- Back from the dead

Neither side honored the plea for a ceasefire. The government accused the LRA of using the peace talks only as an opportunity to regroup. The LRA argued that the talks were a government cover to spot the rebels’ positions. In fact the meetings did often “coincide” with operations by the Ugandan Army. For its part the LRA continued pursuing relentless attacks across Northern Uganda, and its targets came to include religious leaders, whom the group accused of being puppets of the Uganda government.

The LRA also extended attacks beyond the Acholiland into the neighboring territories of the ethnic Lango and Teso people. Pro-government militias, armed and trained by government forces, were established in such areas, and they were also accused of recruiting child soldiers.

The Ugandan Army too were accused of abuses, including “torture and rape, summary execution, and arbitrary detention of suspects” as well as recruiting “boys as soldiers,” a Human Rights Watch report based on field research stated in 2003.

Jan Egeland, the then-UN Under-Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs, referred to the situation as the “world’s biggest neglected humanitarian crisis.”

But the war was nowhere near an end.

*

In an attack against an army position in Northern Uganda, Moses was gravely injured. He felt a strong force that threw him several meters away. Moses first thought he had been shot, but he felt the impact in every part of his body: “The chest, the eyes, the legs,” he told me, pointing to the location of the scars still visible on his skin. He had been thrown by an explosive; fragments of the bomb remain in his body today.

Moses realized he couldn’t walk, so he crawled to a hole nearby and covered himself with leaves. Some fifty army soldiers were in the area, he calculated, and he feared they would seek him out to make sure he was dead.

“I decided to maybe shoot myself,” he said, pointing a finger to his chin, as if holding the gun again. “But I said no. I still have six magazines.”

Blood gushed from his waist, and he pulled his magazine belts tighter to try to stop the bleeding.

The soldiers were near. “I knew they would come and kill me. So I held the gun, and waited,” Moses said, taking position in front of me and looking down an imaginary rifle.

That was Moses’s last memory of the battle. “I fainted,” he said, throwing his body backwards in the white plastic chair and closing his eyes to demonstrate, his legs extended and his arms hanging over the sides. Moses doesn’t know if he fainted because of his wounds, the impact of the bomb, loss of blood, or the scorching sun. He woke up at dusk. He was hurt, stained with dried blood, confused about the passage of time, but fully aware that the Ugandan soldiers might still be around. He spotted smoke coming from a fire, where they must have been cooking.

Luckily, they left before noticing the hole where Moses was hiding. His LRA comrades had also left. He was alone.

During missions ordered by the Control Altar, the brigades had to report to Kony every three hours, via radio, and communicate any incidents. When Moses’ comrades informed Kony that their Brigade Administrative Officer was missing Kony, Moses was later told, was furious. “He ordered some commanders to go and look for me.” But the group never found Moses. Fearing Ugandan soldiers could be close by, he remained in hiding for three days.

For a brief moment, he thought of never returning to the LRA. But then he feared being jailed or killed by the Ugandan Army. He didn’t want his parents to see him in his wounded and disheveled state. So three days later he marched back, deep into the bush. Kony celebrated his return.

As usual in the bush, he had his wounds treated by cleaning them with water and traditional Acholi herbs in the mornings and evenings, and letting them heal.

Among the LRA rebels, Moses became known as the one who rose from the dead.

*

The army’s escalation of violence meant that the LRA fighters had to move carefully. It had become harder to stockpile supplies for the battalions, especially now that they no longer enjoyed the protection and support of Sudan. In these times of intense battles and constant marching to elude their hunters, the fighters were short of two essential items: “Wellington boots and socks,” Moses said.

Back in Northern Uganda, the LRA commanded a chain of “collaborators,” civilians from nearby villages who would smuggle a variety of items to the rebels. Just a month after the meeting with religious leaders, Moses advanced with a group of about thirty fighters to a secret location in the outskirts of Gulu to meet one of these.

Moses had grown obsessed with the idea of seeing his family again. “I kept asking the newly abducted from town for news.” So, that day, besides Wellington books and socks, he had a special order for the boy: “Go and check if my family is okay.” Three days later, the collaborator returned bringing the cargo—and Moses’s father.

This meeting was highly risky for Moses. Even though he was the commander in charge of the mission, he feared that his subordinates, who included two junior commanders, would report him to the Control Altar. What he didn’t know was that the two had been secretly planning to escape themselves. The junior commanders feared Moses, and they may have thought that keeping quiet about Moses’s meeting with his father would increase mutual trust and facilitate their escape.

The efforts of the religious leaders involved in the Peace Initiative had not been entirely fruitless. They had played a significant role in advocating the Ugandan government for blanket amnesty for LRA soldiers, as a way of motivating defections. The Amnesty Act passed in 2000, and the religious leaders took advantage of their meetings in the bush to discreetly inform rebels. A “come home” messaging campaign by local community radio stations had also begun to encourage demobilization.

It was in this context that Moses’s father found his son—heavily armed and surrounded by loyal subordinates.

They greeted each other from afar. Then his father approached. He showed Moses a picture of a little girl. “Your daughter,” he said. “She is seven years old now. And she is waiting for you to come home.”

In high school, Moses had started dating a girl who got pregnant just before his abduction. (Uganda has one of the highest rates of teenage pregnancy in Africa.) Moses’s parents had helped raise the child.

“Come home with me,” his father pleaded. But Moses refused. “There are rules,” he told his father. “Time will come.”

*

Two weeks later, the two junior commanders in Moses’s group told him they needed to return to the site near Gulu to get some remaining cargo. They never came back. Moses’s direct commander blamed him for the loss. The punishment could range from 500 strokes to being beaten to death. This time Moses refused his fate.

“I rejected it. I became so aggressive with the top commanders! How could they?” Moses recalls. “I was abducted as a child, I was a student back home, I am still here, and you don’t appreciate it?” he remembers shouting at them. It was the first time he had confronted his superiors at the LRA. But by then Moses had earned their respect, and the loyalty of his “children.”

The “children,” he said, “were very well trained and very loyal to me, because I was a good commander.” He summoned his unit and bodyguard, and ordered them to shoot anyone who approached him. No one did.

But Moses knew that whatever ties bonded him to the rebels had been broken. He had had enough. From that moment he began planning his escape.

Soon after, Moses heard on the radio that his father had died. Rumors were spreading that the man had succumbed to despair after meeting his son and failing to bring him home.

Nearly seven months passed, and the war only worsened. Moses promised himself that he would see his daughter at least once before he died.

“I was getting a lot of bullets,” Moses recalls. “I decided that the next battlefield would not see me there.”

Three months after his father’s death, Moses’s “wife” escaped. He told his immediate commander that he needed to go bring her back. Moses took his gun and a torch and set off with his bodyguard into the darkness.

But he had planned this all out. A few hours earlier, he had ordered the girl—who was pregnant—to run. He and his bodyguard walked for hours, while Moses pretended to hunt his wife. Then Moses took his bodyguard’s gun and told him to run away too.

Expecting that his bodyguard would return to the LRA camp and report him, Moses climbed a tree and waited. When dawn broke he put on the uniform, which he believed would buy him some time if he was surprised by Ugandan soldiers, and he walked to the nearest army detachment, in Pader district.

He introduced himself as a defector from the LRA and turned in his gun. It was over.

As a commander, Moses was brought to Ugandan Army headquarters in Pader. “You have to give away some secrets,” Moses said. They offered him two options: “Join the army,” through which he could earn good money by local standards, “or go back to civilian life.” The offer of a job was tempting, but Moses was tired of fighting. He chose civilian life.

Moses was granted blanket amnesty, as promised, and airlifted to Gulu, where he was driven home by a Ugandan Army regional intelligence officer.

Moses found his house empty. From a distance, he recognized an old neighbor on the street, and approached him. Realizing the man wouldn’t recognize him, he introduced himself. “Moses Rubangangeyo,” he said.

“I only know one Moses Rubangangeyo,” he heard from his neighbor. “And he died a long time ago.”

Moses would have to rise from the dead once again.

- Searching for Mercy

Moses had lost eight years of his life when he left the bush, and he returned to a collapsed world. Some two million people were displaced by decades of war, and living in extreme poverty in Northern Uganda.

The red clay earth has a more intense tone in this part of Uganda, and local residents say it is colored with the blood of the Acholis. More than one hundred thousand people were believed to have perished in the region between 1987 and 2006, when peace talks started—though those talks collapsed two years later. More than 52,000 people had been recruited by the LRA, half of them children. Many were never seen again.

Yet, more than 20,000 did return. Whether perpetrators or victims—or both, as in Moses’s case—many were rejected by family members and neighbors. They had been held for years, and were often blamed for having adhered to the group.

Returnees were referred to the reception centers run by aid organizations, where they were sheltered and received immediate healthcare and psychosocial assistance. They could stay for up to six months. But Moses felt such services were inadequate to deal with the long-lasting challenges faced by returnees. “They wanted me to stay and learn carpentry with the others. They didn’t believe I could go back to doing normal things, like studying, because I had stayed in the LRA for eight years. They said I was traumatized and would fight,” Moses remembers. “I told them they were wrong, and quit. I just wanted to go home and start a new life.”

He received a “resettlement package”—basic household utensils, a mattress, farming tools, beans and maize seeds, as well as a single donation of 260,000 Ugandan Shillings, the equivalent of $70. “The focus was not reintegration,” Moses said. ‘”We had no further support.”

Moses’s two half-brothers had died in the LRA. Back home, he learned that his older brother had died too, of an undiagnosed illness (during the war, many succumbed to treatable diseases like cholera, hepatitis, and malaria due to the collapse of healthcare infrastructure.) He had also lost his father. His mother was disillusioned and sick.

Moses called Father Carlos, the Catholic priest he had met in the bush during the attempt at peace talks. For a year, Moses contributed his services to the priest’s parish while taking a computer course. He subsisted on vegetables he grew on a piece of family land, and on fish from a small pond his father had built. That allowed him to survive, he said, though not to truly live again.

He realized it wasn’t possible to move forward without looking back. To regain his life, Moses would have to start all over again—from the moment when his life had been interrupted.

*

At age twenty five, Moses returned to Sir Samuel Baker School, which had recently been rebuilt. The fresh paint covering the walls was not enough to erase his memories, however, and he transferred to a smaller school and picked up where his education had been halted.

Father Carlos helped him open a small shop, where he sold part of his harvest to pay for his school fees and support his mother. It wasn’t easy. “I struggled to get through it,” Moses said. “There was stigmatization.”

But in 2012—eight years after his escape from the LRA—Moses graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Development Studies from Gulu University.

In Gulu, returnees could blend in more easily and have better opportunities than those settled in isolated rural areas. Still, that created a situation where perpetrators and victims constantly crossed each other’s path. It was a city of amputees and traumatized people, of orphans and families enduring endless mourning—56 per cent of the families in the Acholi sub-region of Northern Uganda had at least one member who was still missing in 2012, according to a Gulu-based think tank, the Justice and Reconciliation Project.

Their encounters on the streets kept bringing back memories of the war. “Three days won’t pass without me seeing one of them,” Moses said, referring to former LRA commanders who later joined the Uganda army. “And they are receiving big salaries from the government.”

It was March 2014, a decade since his escape. I asked Moses if he had managed to forget his past. “I can live,” he said, ‘”but I can’t forget. It is like a disease. You have to learn how to live with it.”

Then I asked Moses if he could forgive. “I have forgiven myself and have forgiven those who abducted me,” he said. “But forgiving Kony is not easy, because he destroyed my life. He is the one who should be trialed.”

To this day, only one LRA commander has faced trial at the International Criminal Court—Dominic Ongwen. He surrendered to forces in Central African Republic in January 2015, and was transferred to a jail cell at The Hague. The seventy counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity he has been charged with by the International Criminal Court include enslavement, inflicting serious bodily injury and suffering, and conscription of child soldiers—the same crimes that were committed against him.

The trial is of extraordinary importance, for it is the first of a former child soldier, and the court’s verdict can set a legal precedent for future cases. Can children who were abducted, submitted to years of physical and mental abuse in captivity, and who then become perpetrators, be held responsible for their acts? Should the indoctrination they were subjected to, and how it shaped their perceptions of what’s right or wrong, be considered?

“Ongwen was a child soldier like me. We were abducted from school, because the government didn’t protect us,” Moses argues.

While there is no doubt that the LRA’s methods and crimes were horrendous, the politics and interests of national, regional, and international players that allowed—if not fueled—the conflicts for almost three decades are difficult for outsiders to comprehend. Northern Ugandans and experts largely agree that the central government had a responsibility to protect its population, and (purposefully, many believe) failed to do so. Pardoning high ranking commanders such as Ongwen, they say on the other hand, would send a signal of impunity to perpetrators of mass atrocities in Africa. But is it fair to persecute only one side of the war? they ask.

Along with Ongwen, the ICC has indicted Joseph Kony and three other LRA senior commanders—Vincent Otti, Raska Lukwiya, and Okot Odhiambo. Last year, the ICC dropped the arrest warrants issued against Lukwiya and Odhiambo after the court received evidence of their deaths. Otti is also believed to have died, and the court is waiting for DNA tests for confirmation.

Kony remains at large. The LRA is still active, mostly along the border of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Central Africa Republic, from where they abducted at least forty three children in 2019, according to Invisible Children and community-based organizations.

To this day, none of those who sponsored the LRA and provided them safe haven have been held responsible. Sudanese authorities are yet to hand former president Omar al-Bashir to the ICC to face charges for crimes committed in Darfur, in 2003. He has not been indicted for his actions relating to the LRA. The Ugandan government, too, has not been held responsible, despite its many failures to protect its population through three decades of savagery. President Museveni has remained in power since 1986, and Uganda’s parliament recently approved changes to the constitution to scrap the age limit for presidential candidates, making Museveni, now seventy four, eligible for re-election in 2021.

*

In the long-term, Northern Ugandans have been left to their own fate. As the war waned and the LRA moved elsewhere, support for the survivors waned too, perhaps when it was most needed.

Returnees are “commonly abused because of their LRA past,” according to a study by Tim Allen and other researchers recently published in the Journal of Refugee Studies. Like Moses, they continue to be disturbed by their memories. This sometimes manifests in nightmares, high consumption of alcohol, and aggressive behavior, which reinforces stigmatization. As the troubling choices they made in order to survive become known, they are deemed as having “bush mentalities,” or are feared to be carrying cen—a “malevolent spirit” widely believed to possess those involved with violence.

They are, as one local counselor told the researchers, “just half-loved.”

This is true for the women, too—it’s believed that 10,000 girls abducted by the LRA between 1988 and 2004 became child mothers. “Hundreds of them came back bearing children of Kony and Ongwen and others. Those babies, now teenagers and young adults, are ostracized; the girls are getting sexually abused,” Allen said on a phone interview. “And this is happening now.”

In an earlier study, by Professor Myriam Denov, sixty children aged twelve to nineteen—all born to women abducted by the LRA—said “they felt a greater sense of family cohesion” while in the bush, and that they believed their life was better during the conflict than it was afterwards, given the hatred, stigma, and rejection they face.

Those who stayed with the LRA for several years, like Moses, were “more capable to move on,” according to Allen, for “they had to be resilient to survive.” But their reintegration into society depend on a range of things—the help they receive from individuals like Father Carlos; whether they settle in cities, where more opportunities are available; and their education, moral ethics, and religious beliefs. These things mattered more than reintegration programs. In the long-term, instead of fostering social inclusion for children and young adults returning from the LRA, “humanitarian agencies have, for the most part unwittingly, participated in rendering most of them invisible and potentially more vulnerable,” Allen’s research found.

Moses is a rare case. “Many of us are still desperate and vulnerable,” he said. “Some simply can’t cope with the past. For me, it was possible through education.”

In 2018, Moses earned a postgraduate degree in Project Planning and Management from the Faculty of Business and Development Studies at the University of Gulu. “I want to transform my negative experience into something positive,” he said. And he motivated other returnees, like his friend Celere, who spent five years as the abducted “wife” of another commander in Moses’s battalion, to do the same.

Over the years, he and other former abductees have developed their own informal safety net, in which they help each other to cope, bonded as they are by their past and by their shared struggle to return to civilian life. “It is a brotherhood and sisterhood we maintained from captivity,” Moses said. “It is hard to relate to those who didn’t go through what we did.”

Celere almost committed suicide when she escaped in 2009. “So I called her and we sat together.” The last time they spoke, Moses said, Celere had graduated from college and was working for the local government in Pader. She has remarried.

Moses, too, remarried: to a returnee named Mildred, who had spent three years enslaved by the LRA. They met in one of the reception centers. Moses moved—with his mother, his wife, and their children—to rural Gulu, as he could no longer afford the expense of the city.

In 2015, Moses started building himself two buildings with three classrooms each, and he has opened a primary school for vulnerable children from nearby rural villages. Moses shares his time these days between managing the school, working for an Italian NGO that provides assistance to children with cancer, and farming—fresh cucumbers, beans, and collard greens—to increase his earnings and feed his family.

But if he wanted to make peace with his past, there was someone else he needed to seek out: the girl who had been abducted by the LRA at sixteen and turned into one of his enslaved “wives.” His older “wife” had died in an ambush. But this younger one was alive, and Moses knew she had been pregnant at the time he set her free.

He had no idea what happened to her after her escape. So, Moses wrote a letter describing the girl in detail, asking for help locating her. He sent it to NGOs, reception centers, and local councils. But they refused to give him information. So he gave up, until a community leader gave him a tip: He believed the girl Moses was looking for was living in Agago District, 180 kilometers west of Gulu.

Moses went to find her.

He travelled to Agago District several times. His presence roused suspicion, but he managed to discover that she was living in Arum, a small sub-county of Agago. Last year, he learned of a funeral of a man in the village, and decided to attend.

Moses was surprised to learn that the widow was the woman he had been looking for. After she escaped the LRA, she had married a man of her choice, who helped her raise the child Moses had fathered long ago. Out of respect for their mourning, Moses decided to give them time. Eventually he hopes to bring the daughter to live with him, as is Northern Ugandan tradition.

“But, for now, at least I accomplished my mission to find the child,” he said.

The girl is just about the age that Moses was when he was abducted from Sir Samuel Baker School. The mother named her Mercy.

*

To learn more about the child soldiers of Uganda before, during, and after the war, here is a reading list compiled by the author:

—Tim Allen et al. What Happened to Children Who Returned from the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda? Journal of Refugee Studies (2020). Oxford University Press.

—Helen Epstein. Another Fine Mess: America, Uganda, and the War on Terror. Columbia Global Reports, 2017

—Tim Allen and Koen Vlassenroot. The Lord’s Resistance Army: Myth and Reality. Zed Books, 2012

—Matthew Green. The Wizard of the Nile: The Hunt for Africa’s Most Wanted. Portobello Books, 2008

—Kathy Cook. Stolen Angels: The Kidnapped Girls of Uganda. Penguin Canada, 2007

—Tim Allen. Trial Justice: The International Criminal Court and the Lord’s Resistance Army. Zed Books, 2006

—Transcripts of Dominic Ongwen’s trial are available at the ICC website: https://www.icc-cpi.int/uganda/ongwen

Adriana Carranca is a journalist covering conflicts, human rights abuses, and humanitarian crises. She has reported from Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Gaza, D.R. Congo, South Sudan, Haiti, and elsewhere. She is writing a book for Columbia Global Reports.