About six years ago, I started doing a weekly talk show for one of the AM radio stations in my hometown of McKeesport, Pennsylvania, about twelve miles south of Pittsburgh.

The show was the station manager’s idea, and we both stood to benefit: he got free content, and the community website I run, Tube City Online, could expand our audience. Plus, having a talk show gave me an excuse to sit down, unscripted, and pry into my guests’ lives. For someone who’s naturally nosy (in Western Pennsylvania, we say “nebby”) it was almost too good to be true.

I deliberately steered away from politics. (As a newly minted tax-exempt corporation, we need to stay non-partisan.) But that hasn’t stopped us from discussing issues or talking to elected officials. I’ve also talked to musicians, artists, volunteers, clerics, LGBTQ rights activists, labor union leaders, and pretty much anyone else who can spare a half-hour.

The show has featured a lot of entrepreneurs, too. In November 2016, a local independent retail store was celebrating its 70th anniversary, and I asked one of the managers to come on the air with me.

PREVIOUSLY: WHAT’S VEXING MACON?

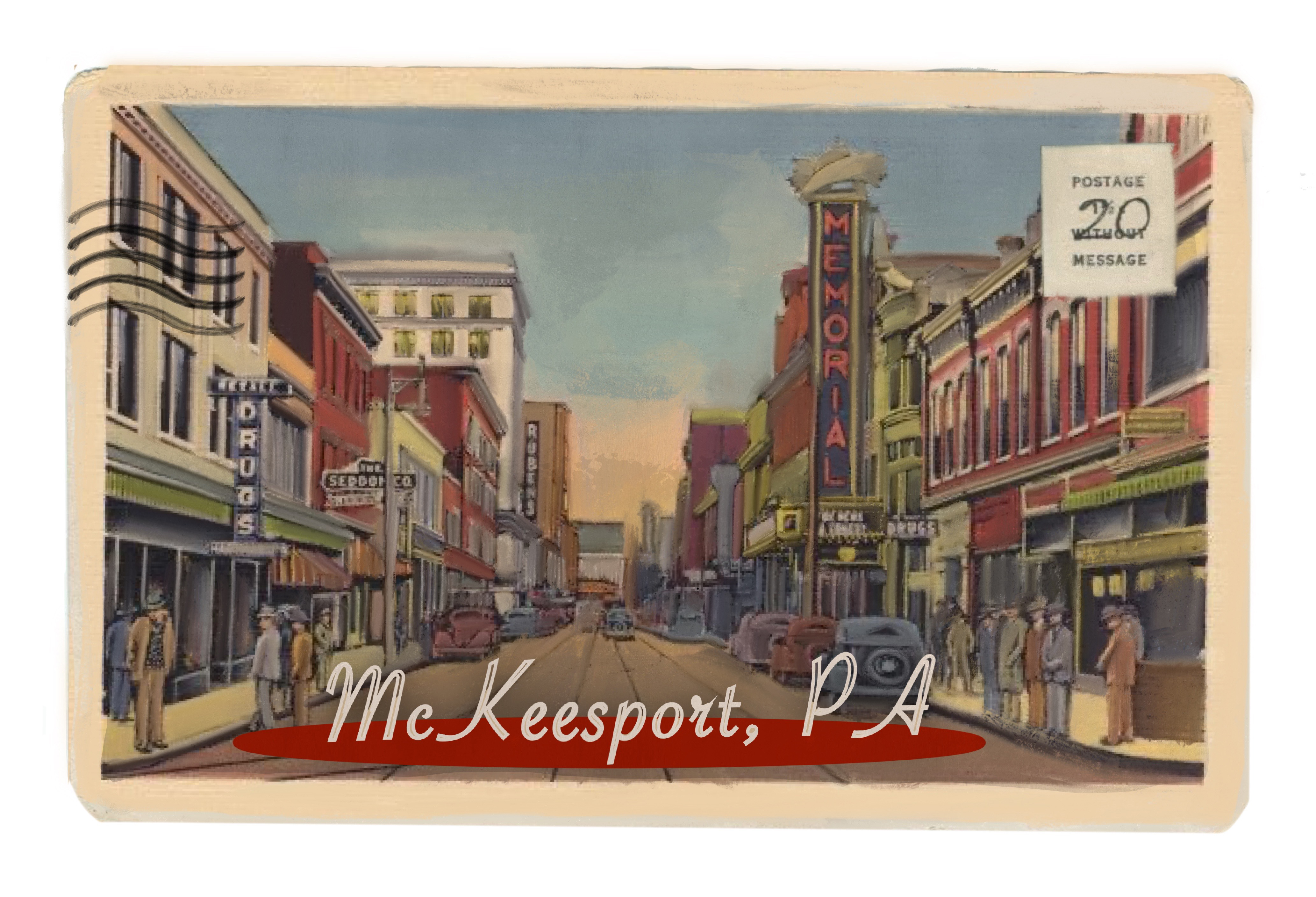

Celebrating 70 years in retailing is a milestone anywhere these days, but it’s especially noteworthy in McKeesport.

In the 1950s, the city’s retail district was one of the busiest in Pennsylvania, behind only Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, with department stores, dozens of specialty shops, a half-dozen movie theaters, and several five-and-ten stores—including, not incidentally, “Store Number 1” of the GC Murphy chain, whose 500 locations in about 20 Eastern states were managed from a ramshackle office complex on McKeesport’s Fifth Avenue.

Back then, about 55,000 people lived in McKeesport—and that figure is deceptively low. Because of the arcane way that Pennsylvania defines municipal borders, McKeesport was ringed with other municipalities like Port Vue, Duquesne, and West Mifflin that were home to another 150,000 residents who shopped and worked in the city.

At any given time, 7,000 to 10,000 of those people worked at US Steel’s National Works—a massive complex, stretching nearly two miles along the city’s Monongahela riverfront, where iron ore, limestone and other raw material entered one end, and finished steel pipes left by trains and barges at the other. The pipes and tubes—from which McKeesport took its nickname, “the Tube City”—ranged from a few inches in diameter to several feet around, and were used in everything from medical and nuclear equipment to the “Big Inch” and Alaskan pipelines.

The development of suburban shopping malls and, especially, the decline of basic steelmaking in the Pittsburgh area gutted McKeesport’s downtown. Between 1979 and 1985, according to one estimate, 113,200 manufacturing jobs were eliminated in the Pittsburgh area. Roughly 28,000 of those were at US Steel facilities in McKeesport and the neighboring communities. Allegheny County—which includes both McKeesport and Pittsburgh—lost roughly 25 percent of its population between 1960 and 2000. McKeesport’s population fell to about 19,000 people by 2010, many of whom are retirees on pensions, or the working poor in service jobs. McKeesport’s median household income today is $28,750—roughly half of the Pennsylvania median of $56,951. Retailers faded away or moved to more prosperous communities.

Still, there are some bright spots, and there’s been some new activity downtown recently; none of us who stayed in McKeesport are willing to give up on the city. But it’s fair to say that thirty years later, vacant buildings still dominate the downtown district. Thriving in that environment is an achievement for any business, which is why I was happy to talk to my guest on that gloomy, gray morning in November 2016.

After the interview, I walked him to the parking lot outside.

“How are things?” I asked.

“Fine, except I can’t believe people were so stupid to vote for Trump,” my guest said. Not only did he find Donald Trump’s victory to be personally offensive, he said, but it also threatened his business: most of the items in his store were imported, and a prolonged tariff war would have the potential to drive up prices. Many of my guest’s customers were public school districts, which could be expected to face budget cutbacks under a Trump administration.

“How could people be so stupid?” he asked

Our cars were parked in the 800 block of Walnut Street. Opposite us was the Salvation Army, and that was one of the livelier places on a Friday morning.

Next door was a decaying four-story apartment building that had originally housed a car dealership. The most recent first-floor tenant, a used furniture store, had gone out of business. The two houses behind the apartment building were abandoned and condemned.

One door down, blue plastic tarps flapped from the roof of a defunct Baptist church, its stained-glass windows long gone. Dirty mattresses sat out front on the sidewalk.

At the end of Walnut Street, we could make out the last remaining remnant of US Steel’s pipe factory, an electric-resistance weld mill employing about 150 people. Because of a slowdown in the natural gas industry, the facility was idled and most of the workforce was laid off.

And in front of that mill, at the corner of Walnut Street at Lysle Boulevard, we could see the one-time home of my former employer the McKeesport Daily News.

In my childhood, the Daily News was a prosperous, 45,000-circulation evening newspaper, locally owned by the Mansfield family. From 1923 to 1934, the publisher, William D. Mansfield, also served in the Pennsylvania State Senate. A beautiful four-lane bridge leading into McKeesport bears his name, and a wing of the city’s hospital was named for the family.

As the city’s retail district collapsed, pages of department store display advertising vanished from the Daily News. For a while, the paper survived on real estate, automotive and help-wanted advertising, but by the early 2000s, even that was shifting to the Internet.

In 2007, the Daily News was purchased by conservative philanthropist Richard Mellon Scaife, and its circulation was added to that of his Pittsburgh Tribune-Review—part of his strategy to outflank the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette by acquiring small newspapers in Pittsburgh’s suburbs.

Following Scaife’s death in 2014, the Tribune-Review retrenched, selling off many of those smaller weeklies and dailies, and closing others, like the McKeesport Daily News, which by 2015 had seen its circulation fall to 8,600 and which printed its final edition on Dec. 31, 2015. Now, in 2016, the presses were gone and the plate-glass windows on the Art Deco building were covered with plywood.

Our website was trying valiantly to fill some of the gap left by the newspaper’s closure. Just before the Daily News closed, I worked with local funeral directors to begin publishing their obituaries online. We recruited freelance writers to cover some community meetings and events. And we launched an Internet radio station. We were offering a fraction of the Daily News’ content—but it was better than nothing.

As we stood there in the November gloom, I gestured to the closed church, the abandoned houses and the boarded-up newspaper office at the end of the street.

“Look around you,” I said. “One candidate said she was going to keep everything status quo. She actually said that. The other guy promised he was going to fix manufacturing and put people back to work.”

“No one really believes that,” my guest said. “What, that the steel mills are going to come back? Trump’s going to bring back the steel industry?”

“No, but McKeesport has been suffering for years,” I said. “Then you hear Hillary Clinton saying that America is already great, and we need to keep the status quo, and if I’m standing in this parking lot, I’m thinking—we want to keep this? This? And then this celebrity comes along and promises he’s going to put people back to work and make everything great again.

“I’m not saying they made the right choice—I am saying I can sympathize with anyone who decided to take a chance.”

I still sympathize with them. But I have to admit that the dominant narrative—that Rust Belt places such as McKeesport voted for Donald Trump because of decades of decline and deep-seated economic anxiety—is seriously flawed.

McKeesport residents, despite all of their city’s struggles going back to the Reagan years, voted overwhelmingly for Hillary Clinton in 2016. Clinton won twenty-eight of the city’s thirty-two voting precincts — many of them by more than fifty points. One small precinct in the city’s Seventh Ward went for Clinton by a margin of 164 to 8.

Meanwhile, neighboring White Oak is a relatively well-to-do community (median income $56,316) and now houses much of the retail and professional activity that was once located in McKeesport’s downtown. Voters there went for Trump, 2,375 to 1,764.

In nearby Liberty (median income $47,425) voters favored Trump, 780 to 451, while Elizabeth Township (median income $60,068) went for Trump by nearly a two to one margin.

Besides their relative prosperity, what sets those communities apart from McKeesport is their racial makeup.

In McKeesport, according to the US Census Bureau’s most recent estimates, 60 percent of residents identify as “white alone,” roughly 34 percent as “Black or African American alone” and roughly 5 percent as two or more races.

94 percent of White Oak residents identify as white. In Liberty, it’s 97.6 percent. And of Elizabeth Township’s 13,271 residents, only 167—1.3 percent—identify as “Black.”

Across Allegheny County, voters in 2016 chose Clinton over Trump, 366,934 to 259,125. But on an electoral map of the county’s precincts, it’s almost comically easy to see which municipalities are mostly white and which ones have a high percentage of Black residents.

According to the census, Duquesne, directly across the river from McKeesport, is roughly 30 percent white, 57 percent Black and 12 percent mixed-race. Voters there chose Clinton over Trump, 1,780 to 430. Dravosburg, which is part of the McKeesport Area School District, is 94 percent white. Voters chose Trump, 473 to 342.

If it’s too simplistic to say that “economic anxiety” motivated voters in 2016 in the Rust Belt communities around McKeesport, it’s also too easy and wrong to say they were motivated totally by racial attitudes.

Yet there may not be another part of the United States that is so sharply divided along racial and economic lines as the Pittsburgh metropolitan area—and where those racial and economic characteristics map so closely to political attitudes.

We all know about the gaps between “red states versus blue states,” and the divide between “rural and urban” Americans. Around Pittsburgh and McKeesport, it’s “red streets versus blue streets,” and “red suburbs versus blue suburbs,” and although the stakes are smaller, the gaps between the two sides are no less real.

NEXT WEEK, CHAPTER FOUR: ONE TOO MANY PRESIDENTIAL INSULTS FOR A TEXAS BORDER TOWN

This project is supported by a gift from the Delacorte Center for Magazine Journalism Fund at The New York Community Trust.

Jason Togyer is a lifelong resident of the Monongahela River valley area of Pittsburgh. He and his wife, Denise, live just outside McKeesport. The founder of Tube City Online, a non-profit news website and Internet radio station, Togyer also serves as communications manager for a regional community development agency and previously worked as a magazine editor at the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University, and as a reporter for the Washington, Pennsylvania Observer-Reporter, McKeesport Daily News, and Greensburg and Pittsburgh Tribune-Review.