This story was published in Issue 2: Silence.

Listen to a conversation about this story with author Natasha Rodriguez and publisher Michael Shapiro on the Delacorte Review Podcast.

*

I.

Close in on Calle Linea in Havana. Stop looking at the old cars driving past; the chapped earth; the pavement split open at every step, never repaired; the stray cats, half dying; the sweating bodies on tired benches, waiting for crowded buses. Always the waiting.

Stop smelling the rotting garbage simmering in plastic bins. Stop listening to the street peddler, crying out about the garlic he is selling from his metal cart. Focus on an apartment building. Four stories tall, yellow under its dust. From a window on the third floor, a whisper of music.

Focus on the music.

Voy a contarte mi realidad/La realidad de mi barrio/Como es que se vive /Loco es el vecindario/Se ve a gente luchando/Solo para obtener el diaro

I am going to tell you about my reality/The reality of my neighborhood/how they live/The residents are crazy/You see the people struggling/Just to obtain the daily necessities

There is music. It fades in and out, drowned out by life.

This isn’t the kind of music that’s heard often in Cuba. It isn’t salsa or reggaeton. It isn’t Buena Vista Social Club or whatever is charting in America. It’s foreign but at the same time it could not be more Cuban.

It is rap. And rock. And funk. And jazz. There’s a guitar and a bass and drums and a singer and a rapper. But above all, it is rap.

Trato de buscar una salida/Pero no comprendo/Porque llevan esta vida/No hay sueño/No hay futuro/Todo esta en oscuro/La necesidad es algo super duro/Pero lo mas duro es que no luchan/Por algo mejor/Suéltalo

I try to find an exit/But I don’t understand/Why they have this life/Without dreams/Without future/Everything in the dark/Necessity is something really tough/But the hardest is that they don’t fight/For something better/Let go

These words are rapped over live music and background vocals. The song is Mi Realidad. My Reality. The group is New World. The rapper is Yosvel.

The group rehearses in a two-bedroom apartment in the yellow building. The musicians, seven of them, can barely fit in the room with their instruments and their equipment. The room is bare, nothing on the walls, no real furniture. If you sit in the rehearsal room the music will greet you like a wave crashing into your face. Your body will feel vibration after vibration.

New World rehearses weekly because work is unpredictable. The next time they perform in public could be tomorrow or in a month. Or never.

This music that is so loud, so bold when you’re in the middle of it, could become almost inaccessible within the year. There could be no rehearsing in homes, no gigs in bars and clubs, no playing at parties, no recording sessions.

Throughout the world Cuba is known for its revolution, its politics, and its music. Cuba prides itself on the talents of its artists. And yet, Cuba has never really figured out how to treat its artists.

Fidel is gone, dead for three years now. Raul is no longer in charge. The new president is Miguel Diaz-Canel. And one of the first laws that he signed, in April 2018, was Decree 349. It was ratified in December 2018. It is slowly being rolled out today. The new law prohibits all artists, including musicians and performers, from operating in public or private spaces without prior approval by the Ministry of Culture. This means that in order to perform or exhibit in Cuba, any independent artist has to be represented by a government agency.

And any individuals or businesses that hire artists without authorization from the government can be sanctioned. Artists who work without authorization can be substantially fined and have their equipment or materials taken away. Authorities also have the power to immediately suspend a performance. Such decisions can only be appealed before the same Ministry of Culture.

The law also prohibits any materials that contain the “use of patriotic symbols that contravene current legislation” (Article 3a), “sexist, vulgar or obscene language” (Article 3d), and “any other (content) that violates the legal provisions that regulate the normal development of our society in cultural matters.”

The law, in other words, gives the government complete control over artists. Most artists in Cuba are against the new law but the majority of them refuse to speak out against it. They refuse to sign petitions. They skip the protests. If they did raise their voices, if they made some noise, they could be blacklisted, censored, done.

This law is not surprising to Cubans. Cuba has always been restrictive, stifling. This is just another way for the government to control them, they say, without batting an eye. It is exhausting but it is familiar.

**

This law will harm all independent artists in Cuba, but rappers are among the most vulnerable. Most of them don’t belong to an official agency. They record in underground studios and are always in search of performance venues. Rap has been losing its momentum. Few people want to book rappers. Few Cubans even listen to Cuban rap today.

And the rappers are frustrated. There is no money in rap. Clubs and bars are hesitant to book them as musical acts because they worry that no one will show up. On the other hand, some also fear the crowd that often will come—black Cubans. Many rappers give up, move on. They record reggaeton instead, or decide to pursue a different career. Some try to leave the island.

But other rappers refuse to surrender to all the challenges—a new law, a public whose tastes have changed, a seemingly impossible path to success. They keep working, keep trying, keep wishing, keep dreaming. To be a rapper in Cuba means to live in rap. If you have not dedicated your life to rap, if you do not have that drive and passion, you will not make it.

If you are not Cuban you must understand that Cuba is very different from where you are from. There is no real incentive to work hard. There are no bonuses waiting for you. The Cuban workforce is a largely unmotivated one. Employees will rarely go out of their way to accommodate you, unless you are a foreigner with money.

And remember, too, that Cuba without music is not Cuba. The island would be unrecognizable without the reggaeton blasted at maximum volume from just about every car; the Son Cubano played by the Malecon, the beautiful seawall that extends along the coast of Havana; the Buena Vista Social Club repeated over and over for tourists in Havana Vieja. Somewhere in the mix is Cuban rap, and the brave men and women who create it.

El malecon

To understand Cuba is to know its music. To understand its music, you must know how much it is controlled today and how much it is changing. Cuba is changing, always. That’s what the outside seems to forget.

II.

New World has a concert coming up at la Fabrica de arte Cubano (FAC), a club-cum-music venue-cum-art gallery. The large space, an old peanut oil factory, seems as if it belongs in hipster Brooklyn though it is more innovative and fun than anything there. There is live music every night that it is open. Sometimes there are fashion shows, movie screenings, plays. FAC was created by X Alfonso, a Cuban musician who is well respected on the island. It costs two CUC (two US dollars) to enter, making it difficult for the average Cuban to afford, since the average Cuban makes around $30 a month. On most nights, the crowd is made up of tourists and wealthier Cubans, and also young hip Cubans who somehow manage to get in. Everyone at FAC seems interesting, chatting up friends and strangers, hanging out near the many bars, smoking cigarettes in the open-air areas, dancing until four in the morning.

Yosvel is at home in FAC. He can’t walk for long without people stopping him to greet him, to make small talk. His father is the head of security at FAC and so everyone who works there knows who he is. But FAC is also the nighttime destination for many Cuban artists. They all seem to know Yosvel.

I want to see Cuba before it changes, some people say.

Perhaps they don’t think about what it means to say this—that they want to see a country in all its splendid squalor. They want to see Cuba before its buildings are renovated and its roads are repaved and its aging cars are replaced with newer models. They want to photograph its cracked walls. They want to listen to Buena Vista Social Club and drink Havana Club. They want to mingle with the people with wrinkled faces, worn by the sun and hard work, and ask about the Revolution. They want to eat ropa vieja and marvel at how cheap everything is.

They can’t wait to go back and show friends this raw and beautiful Cuba—this building with the chipped blue paint and ruptured stairs, these worn clothes hanging out to dry, those children playing in the rubble, this fading Che Guevara street art, this pink 1950s American car with a Russian engine. To many foreigners, Cuba is a relic of the past.

But time didn’t stand still on the island when the Revolution triumphed in 1959. Cuba is changing. It has always been changing.

So have its people. The people, who perhaps have never tasted ropa vieja, which is only readily available to tourists, and who are not allowed to set foot inside the luxurious hotels in their own country. The people, for whom time never froze, for whom life is hard and beautiful and exceedingly complicated.

Cuba, which seems so backwards to some, has free education for all its citizens. It has one of the best healthcare systems in the world and one of the highest literacy rates. It’s full of life and culture and beauty. In some ways it is progressive, and in others woefully regressive.

Its citizens cannot freely speak their mind. They cannot go and come as they please. Most have never left the island, and those that do often never return. They don’t have free access to the internet in the comfort of their homes. They don’t have the freedom to create—to paint, to write, to sing what they would like to sing. Many Cubans refer to the rest of the world as the outside, el exterior, as if they are trapped inside.

In Cuba, the heat will wrap its arms around you in a tight embrace and begin to suffocate you. And the heat doesn’t work alone. As you walk down Havana streets, dust and car exhaust try to blind you. Isolation, too, creeps up. It cuts you off from anything beyond the island. The Malecon’s concrete wall reminds you that there is a world beyond, a world where you are allowed to move without restrictions, to speak without thinking, even to shout.

And yet, there are times when the night breeze from the ocean caresses your body. When people are eager to talk to you, and the music lights up the island with its electricity. When you don’t want to be on the outside, and you are certain that no other place is as magical as Cuba. When you have never felt more alive.

**

Cuba’s revolutionary heroes are young because many of them died young—El Che, Camilo Cienfuegos. And yet most of Cuba’s youth today does not fight. Cuba’s youth does not want to grow old in Cuba. By the year 2050, Cuba will be one of the countries with the oldest populations in the world. People who once swore they would never leave their birthplace are now desperately searching for ways to leave. The island is getting worse, they say. There is no hope, they say.

When the US restored diplomatic relations with Cuba, in December 2014, people were hopeful. But the wet-foot/dry-foot policy—which allowed people who emigrated from Cuba and reached the US to remain in the states and pursue residency a year later—was dissolved in January 2017, making it harder for Cubans to immigrate legally to America. In the middle of 2019, the Trump administration made it harder for Americans to visit Cuba. No more cruise ships full of tourists, and their dollars.

Still, the door to the outside world had opened up a crack. Through this crack Cubans were able to see more clearly what the rest of the world had, and notice what they themselves did not have. Meanwhile young Cubans are increasingly present on social media, a place where one is guaranteed to see wealth and excess and brand names being flaunted. So they wear knock-off Supreme clothing. They tattoo their bodies with the Apple logo. They open imitation MacDonald’s restaurants. In Cuba, people have this idea about “el Yuma.” Anything coming from “el Yuma”—the exterior, but more specifically the US— is something to imitate.

It goes without saying, of course, that no other country has had a bigger influence on Cuba than the United States. There’s the embargo, which in Cuba is referred to as “el bloqeo.” There are the decades of US attacks on Cuban leaders and crops and food. There’s the laughable failed CIA plots to assassinate Fidel Castro. There is so much.

After the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, all things American, all things capitalist, were banned from Cuba. But when a government attempts to keep something from its people, its people grow curious, thirsty. Because they weren’t allowed to learn about American culture, they found ways to consume it. From the beginning of the revolution, Cuba prohibited American music, the music of the enemy.

So naturally, everyone wanted to listen to this forbidden music. Cubans found alternative ways to listen. They would go to the beach, head towards the ocean. Florida is 90 miles away, and if they got lucky, they could listen to—and record—FM radio. Then, at parties, they would dance to recorded American music. Isolated from everything, they wanted to explore the unknown.

III.

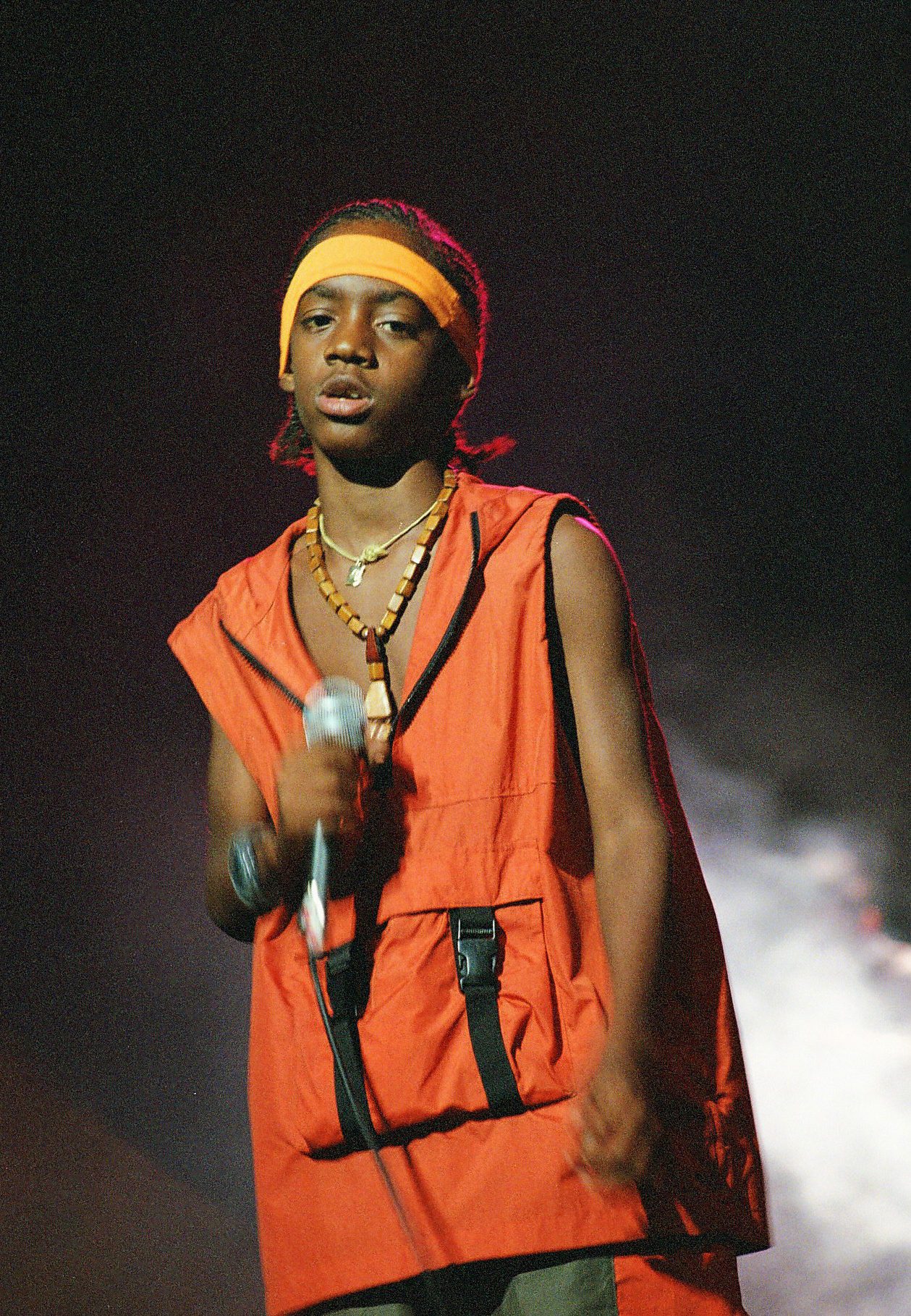

Yosvel

Yosvel, New World’s founder and rapper, has performed at FAC before. But he prepares exhaustively for each concert. So they rehearse in the cramped room twice a week instead once a week. One Monday, after rehearsal, Yosvel says they played so well there is no need to rehearse again on Wednesday. It is a joke. They will be back Wednesday and play through the entire set list, ironing out mistakes.

Yosvel is almost always upbeat, carefree, and loud. He is twenty-four, and in many ways, a typical twenty-four year old. He loves to go out, to see friends, to spend nights drinking rum and exploring Havana nightlife. Yosvel is always in motion, flitting about, unless he is sitting in front of the television, playing his favorite soccer video game. It can be quite strange to see him in rehearsals, where he is extremely professional, or when he is downcast, which is rare. But he has been working for seventeen years now. In some ways, he is more grown up than most.

In 2018, Yosvel participated in a yearlong Santeria ceremony in which he was “crowned” by his parent god. For the duration of the year, he was referred to as “iyawó.” He was only allowed to wear white clothing as a sign of purity, a contrast against his dark skin. He could only sip from white cups and touch food with white utensils. When he went out, he brought a white travel mug and a white spoon with him. When he saw another iyawó in the street, he had to acknowledge them with a bowed head.

Yosvel stumbled into rap at the age of seven because of his older brother, who loved to rap at home but was too shy to perform in public.

But Yosvel wasn’t scared.

He began to rap at home, on the streets, in the school. His father wrote him a rap. Yo me llamo Yosvel, it began. His mother used to beg him to stop. But the raps accompanied him everywhere, a soundtrack to his life.

When he was seven, his mother took him to a friend’s recording session at Abdallah, the Silvio Rodriguez-owned recording studio, regarded as the best in Cuba. The session bored Yosvel. He wandered out into the streets and began to rap. Yo me llamo Yosvel. People stopped to listen. He began charging his spectators. One peso for one rap.

In the midst of this, Yosvel caught the attention of Luis Frank, a singer from Buena Vista Social Club. Frank demanded to know where this child’s mother was. She came out of the studio, apologizing for her son—he must have been disrupting people again, she thought. But Frank was impressed. He wanted Yosvel to rap over one of Buena Vista Social Club’s songs. Yosvel’s mother thought it was a joke. At the time, her family was barely scraping by. She didn’t have the luxury of getting her hopes up.

Some days later, Frank called their neighbor’s house. He asked Yosvel to come to the studio. And he did, recording his rap in a single take. The song, Yosvel en si, features mostly just Yosvel, rapping over lively son Cubano with some backing vocals.

After the session was over, Yosvel wasn’t satisfied. “I want to do another song,” he told them. “I want to do two.” Everyone agreed. He recorded another song, once again rapping his section in one take. He earned 400 pesos for each song.

“I wasn’t aware of what it all meant,” Yosvel recalled. He was just a kid. He had no idea who Luis Frank was or what Buena Vista Social Club and Studio Abdallah were. To him the experience was wonderful but it was also just a nice place with free cookies and ice cream where he was able rap freely.

But soon after the song was released, Yosvel began touring with Luis Frank and performing with X Alfonso. He appeared in an X Alfonso music video, called Santa. He was nine years-old, big hair almost to his shoulders, a crescent moon painted over his bare chest. Staring directly into the camera, he seemed to possess all the confidence in the world. The music video took off in Cuba; everyone saw it, everyone knew Yosvelito, the little boy who rapped.

Yosvelito performing

“I couldn’t go out on the streets,” said Yosvel. “It was really difficult. Everyone wanted a photo. I was nine years old. I had to know how to do my signature and I barely knew how to write.”

To this day, Yosvel is recognized by some people who remember the video. Sometimes, when they realize who he is, they cry. The Santa music video got seventeen nominations at los Lucas, which is the Cuban equivalent of the Grammys. It won fourteen awards, a record that has yet to be broken. Yosvel keeps two of the awards on his bookshelf.

Yosvel grew up in the Havana rap scene. He was the only preteen allowed in Havana clubs and music halls. He toured the country with Frank and X. He was invited to perform at a farm with Buena Vista Social Club, only to get there and realize it was a concert for Fidel Castro himself.

He grew older but he always had the same look—dark skin, silver and black bracelets on his wrists, long thick braids. In high school, Yosvel was asked to cut his hair. All schoolboys in Cuba must have closely cropped hair. But Yosvel refused. He told his parents he would rather drop out than cut his braids off. His parents turned to X Alfonso, who turned to the then Cuban Minister of Culture, who turned to Raul Castro. The next day, Yosvel brought a note to school. It was signed by Raul Castro. He did not have to cut off his hair.

After years of touring with other musicians, Yosvel decided to form his own group. He was sixteen, itching to do something new. At seventeen he created the first iteration of his group. It had a guitarist, a bassist, a drummer, another rapper, and a DJ. From the beginning, the group was called New World. This marked Yosvel’s first time directing a group.

But “It was a total disaster,” he said. Nothing worked. He dismissed all of his musicians and found new ones. This time, he made it his mission to only recruit people who came from the streets like himself, people who didn’t study music in school, people who weren’t professionals. But this group didn’t work out either. He started from scratch, again and again and again.

“For me, it has always been very difficult because there are musicians who come in and see New World as a hobby,” said Yosvel. “Music has never been a hobby for me, I’m not accustomed to see it that way.” A lot of musicians who joined New World wanted to get fast results, right away.

“Music isn’t like that,” said Yosvel. “You have to treat it with patience.”

Being in New World is not lucrative. Yosvel can only afford to pay his musicians when there is work and when that work is paid, although sometimes when work is slow he pays them from his own money. Each gig pays differently. It can pay nothing, it can pay around $40 or $80, and sometimes it can pay $600.

Around three years ago, New World became the group that it is today. The band has progressed as Yosvel has matured. Today he is more confident; people take him seriously. He is extremely demanding of his group. New World is his first child, he likes to say. But New World hasn’t yet found the success that Yosvel dreams of.

IV.

On the day of the concert at FAC, a large and costly car is ordered and the New World musicians load all the equipment they need for the evening show into it. The car travels up Linea, one of the main streets in Havana, towards FAC. Those who do not ride with the equipment take maquinas (taxis that run like an Uber pool, with distinct routes).

Once at FAC, a man who doesn’t smile lets New World in through a sliding wooden side door. The place is bustling. Everyone is running around with cables or crates, trying to get things in order. New World runs through some of its songs with the sound engineer. Yosvel asks him to make the bass sound softer and to fix the audio on the drums.

The musicians seem nervous, uncomfortable. They clutch their microphones. Sitting on two stools to the side of them is Yosvel’s wife, Zoe, and her friend who is visiting from the states. Zoe records everything, propping her iPhone up on a bench.

Rap came to Cuba the way most imports from America come to the island: in secret. It was discovered via radio and TV broadcasts from Miami around the 1980s. In the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the beginning of the Special Period, rap was used by Cubans—especially black Cubans—as a means to express their frustrations.

The Special Period began in 1991 with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, leading Cuba to suffer a severe economic depression. It was trying. Without its ally, Cuba lost 80% of its imports, 80% of its exports, and its GDP dropped by 34%. The country was devastated by shortages of hydrocarbon energy sources and reductions of rationed foods. Cuba-Russia relations improved in 2000, with the presidency of Vladimir Putin.

But meanwhile the Special Period changed Cuba and Cubans forever. Ever resourceful and resilient, this decade of hardship forced Cubans to create sustainable agriculture systems that did not require petroleum. It forced them to deal with massive power outages, to live without effective public transportation and industrial systems. Food consumption was cut back to one-fifth of what it had been before. Hunger was a daily experience. People were forced to eat whatever they could, including zoo animals and stray cats. The average Cuban lost twenty pounds. Those who were able to leave the island—the majority of whom were light-skinned—left. Many who weren’t able to leave tried to leave anyway, in makeshift rafts and tires.

Rap was a way for Cubans to express their feelings and their struggles during this difficult, often hopeless time. In the beginning, rap was eyed with suspicion by the Cuban government and by some of the population, as another form of cultural invasion from the United States.

This changed in 1999, when the Cuban government declared rap to be an “authentic expression of Cuban culture.” The government soon formed the Agencia Cubana de Rap (Cuban Rap Agency), which featured a state-run record label and a hip hop magazine. The agency supported groups that were willing to change their lyrics and music styles to something that would be supported by the government. Fidel Castro even referred to rap music as a “Vanguard of the Revolution.”

However, the establishment of the Cuban Rap Agency led to the birth of the Cuban underground rap scene. Because the agency didn’t tolerate rappers and lyrics that were critical of the government, rappers who wanted to express the harsh realities of Cuban life through rap did so underground.

That includes the reality of racism. Because racism was officially declared to have been eliminated from Cuban society in 1962, public discussions of racism and discrimination are deemed subversive. Cuban youth drawn to rap have always been, and continue to be, largely darker skinned and from marginalized backgrounds. The police often discouraged these rappers from visiting nightclubs and restaurants that were intended for tourists. So they formed their own spaces, often in people’s homes, where they could express themselves.

The underground rap duo Los Aldeanos became known for speaking out against the Cuban government. When people listened to Los Aldeonos, they often cried. They had found artists who understood their struggles, artists who were not afraid to criticize those in power. Although Los Aldeanos’ music is banned by the government and censored by the press, the group’s music has been heard by probably every single Cuban on the island—an impressive feat, considering that their songs have never been played on Cuban radio.

But Cuba is always changing. And after the Special Period, many people did not want to continue to listen to music that reminded them of what they had endured. They wanted to move on, to forget. And so they turned their attention to other genres of music.

Today, Cuban rap is dying, in all of its forms—underground rap, Cuban Agency-backed rap, freestyles on the streets. What remains of the Cuban rap movement is mostly underground. Cuban rappers rap about life, about the good and the bad and the ugly and the fucked up realities of real people. But so many people don’t want to be reminded of their problems. It’s hard enough to live a day in their life, they say. They don’t want to think about all that. They don’t want to think, period.

Why think when you can lose yourself, you can escape, you can numb your mind with music like reggaeton, which doesn’t say a thing about anything?

**

Reggaeton is a musical genre that is influenced by hip-hop and Latin American and Caribbean music. Reggaeton artists typically sing and rap in Spanish or Spanglish, backed by thudding synthesized beats and reggae—or merengue or plena or bomba or salsa or some mix of several of these genres. There is always a catchy chorus that is repeated over and over again. One reggaeton song sounds pretty much like the next.

According to some music historians, reggaeton originated in Puerto Rico during the late 1990s. According to others, it originated in Panama during the 1970s. However, most historians seem to agree that it began to gain traction in Puerto Rico during in the 90s. This musical genre was first an underground one, played in the clubs of San Juan and spread through informal networks and performances at unofficial venues. The Puerto Rican police were initially against reggaeton, and they launched a campaign against underground music by confiscating cassette tapes from music stores under obscenity penal codes. Reggaeton was distributed through bootleg recordings and word of mouth, until it was discovered by international audiences in the early 2000s.

With the appearance of artists like Tego Calderon, Ivy Queen, and Daddy Yankee, whose 2004 song Gasolina became a mainstream hit, reggaeton became popular in the United States and in Europe in the mid 2000s. And since then, reggaeton hasn’t stopped growing. There are many reggaeton and reggaeton-adjacent artists today—J Balvin, Nicky Jam, Ozuna. The rise of music-streaming platforms has no doubt helped grow reggaeton’s global influence.

Critics of the genre say the music is demeaning to women. Many lyrics focus on the objectification of women, on sex and seduction. While there are many female reggaeton artists, the genre is certainly dominated by men. And like many other musical genres, the majority of reggaeton artists who gain popularity are light-skinned.

In Cuba, reggaeton has taken over. It’s more popular than salsa, than jazz, than rap. Cubans play reggaeton music in their houses and cars, at parties and beaches. They record their own reggaeton songs. They dance to the thudding bass, and to lyrics that don’t invite thought. As one rapper explained the phenomenon, “People prefer to dance than to listen to some sort of social critique.”

V.

Yosvel met his wife, Zoe, in 2014 when she was studying abroad in Havana. They had seen each other at FAC several times and one day they hit it off. Although Zoe is American and Yosvel is Cuban, they managed to form a strong relationship. Yosvel has never been to the United States. Zoe resides mainly in Havana, where she is the assistant director of an American study-abroad college program. She is from Minneapolis, and her parents visit Cuba often. They fell in love with the country and with Yosvel some years ago.

Zoe works hard to help the group. She had New World T-shirts made and printed New World stickers that she sent in letters to her American friends, asking them to paste them on the walls of their cities. Sometimes she works on booking gigs for the group. But it is not easy. She once managed to get New World a somewhat steady gig preforming at a local bar but when ownership changed it was over. The new owner refused to book rap. He wanted salsa.

Life for rappers is hard. Decree 349, the new law that supposed to go into effect sometime this year, could make it harder. Everything will have to go through the government, meaning that all artists who want to work and perform will need to have papers. You can get papers by auditioning for an agency under the Ministry of Culture. Rappers, for example, must get papers through the Agency of Rap.

This is easier said than done.

If the Agency of Rap doesn’t like your audition, you won’t get papers. If they do like you, you can be approved, but that process can take a long time—up to two years for some artists, between the time of your audition to the time you get your papers. With these papers, you are considered a “professional artist.” You will be recognized by your government as an artist. You will exist.

But you will still struggle.

The agency will take twenty percent of all the profit you make for concerts and paid engagements. They will not help you find work. When you get working papers, you have a six-month trial run. If you don’t find any work in those months, the agency can kick you out. If you belong to the agency later and you have a dry spell, unable to find work for months at a time, five months, six months, the agency can give you an ultimatum. It can take your papers away.

One positive aspect of belonging to the Agency of Rap is that you can work legally and people will regard you as a professional. Yet sometimes you won’t make a profit and you will lose money. But you will have papers. People will look at you with less fear.

But if you do not have papers, no bar will legally be allowed let you play, once this law is fully rolled out. Owners will not contract independent artists. If they do and an inspector finds out, the bar will be shut down. Without papers, even rehearsing in a private residence is illegal. If you are found out, all your equipment could be confiscated—your speakers, microphones, instruments. You can be fined.

Cuba transforms doing things legally into an impossible task. This is why people do things illegally. It is much easier to just rehearse in your house illegally than to try to obtain permission. “I don’t think that in Cuba there is a single musician that does everything legally in order to become a musician,” a rapper said. “It would be impossible. It’s impossible.”

VI.

La Reyna y la Real

La Reina y La Real is one of the few rap groups in Cuba today that is fairly well known. And the duo is the only female rap group that performs regularly in front of a public audience. But despite booking gigs here and there, despite touring internationally, La Reina y La Real struggle. They live just like any other Cuban. Money is tight. The future is uncertain. They take the bus on the corner. They live far from central Havana.

It is probably impossible to focus on anything but the stage when La Reina y La Real are on. Last August, at la Fabrica de arte Cubano, the two rappers seemed to be the only two to exist as they performed. Their voices were powerful, the music was electrifying. They radiated joy. They rapped about women, about freedom, about refusing to serve men.

Voy bajando y que se quema el arroz! they sang to an audience that couldn’t stop cheering. I’m leaving, let the rice burn.

The group consists of two women—Reina and Yadira (la Real). Both are thirty-two. Reina has dark skin and long black braids, and she has a son. She was an industrial chemist before she left everything behind for rap eleven years ago. Yadira, who has been a rapper for sixteen years, is also black, but with fairer skin. She has short hair, some of it bleached. She likes to wear bright lipsticks and long earrings. Yadira was pursuing a degree in psychology before she gave it up to pursue rap.

They had no idea how difficult it would be.

“In Cuba there are rappers whose lyrics, whose forms of expression have been against the government,” said La Real. “And everyone thinks that that’s what rap is all about, and they immediately reject it without listening to your music. They don’t even give you a chance. We have to work twice as hard.” The two have been a duo for six years. They joke a lot and interrupt each other’s sentences. As is the case with most Cuban rappers, neither studied music professionally.

La Reina y La Real have struggled with their identity within the Cuban rap world. When they began rapping, they said, they imitated the male rappers. They dressed like them, rapped like them, behaved like them. It didn’t work.

Eventually, they focused their energy on what they really wanted to do—being unapologetically female. “People criticized how we were dressed all the time,” said Reina. “They told me I should lose weight, they said I don’t look like a rapper. I represent women. I’m a woman from the neighborhood. I’m a mother. Maybe if other women listen to me, they can relate to me.”

Their rap, they claim, is for everyone, but their message is directed at women. “They say that women always cry, that they complain about everything,” said La Real. “Little by little, we’ve tried to get those ideas out of their heads. We don’t cry. We stand up for ourselves. We defend what we want. We defend what we are.”

Some rappers say that La Reina y La Real are not real rappers anymore. They say that their music is fusion, that they are reggeatoneras, salseras because they rap over live music.

Some rappers even stopped inviting La Reina y la Real to perform in rap spaces and rap festivals. “These rappers think that being a rapper means singing at La Madriguera or improvising drunk on the streets,” said Reina.

But while La Reina y La Real do sing, while they do have a band behind them, they still rap. And rap is the core of every song. “I want our songs to make you dance,” said La Real. “But I also want them to make you stop and think about what we are saying.”

In Cuba, many think that rap can only be one thing—one voice spitting rhymes over a backing track. And it is this notion that is part of the reason why rap is disappearing. Because rappers themselves are part of the problem. Rap purists reject non purists. They don’t let the form evolve. But a genre cannot grow with this mentality, and so it starts to die.

La Reina y la Real met in 2010 at a club where rappers used to meet up every Wednesday night. Soon after, they began recording songs together, using tiny microphones, the ones on headphones that you use to talk on your cellphone. When they auditioned for the Cuban Rap Agency, they were told there was very little capacity so they had a better shot at getting in if they worked together. And so they became La Reina y La Real.

After their audition, the agency told them they would work better as individuals. You should separate, they said. Instead, La Reina y la Real decided to redo their image. They stopped imitating men. This way, they found some success.

Fame is not their goal, however. Fame is fleeting, they said. We want our music to be victorious. We want our music to stay in the hearts of the people who listen to it, they said.

In fact, fame is unrealistic for a rapper in Cuba. “My country doesn’t offer the possibilities to make it,” said La Real. “It keeps telling me, go to another country, find success there and we might recognize you after you do that.”

This is what happens in Cuba. It happened with Orishas, with Gente de Zona, with countless others. You have to leave the country to find people who care about your music, people who allow you to perform your music. If you are successful on the outside, there’s a chance that Cuba will want you back, will want to claim all your triumphs as its own.

La Reina y la Real toured the US once, performing at college campuses. The reception was warm. They were shocked, they said, to see how people treated them. They encountered kindness. “They respect me more outside of my own country,” said La Real. “It makes me so sad.”

VII.

New World has yet to record every song the group performs live. It takes forever to record anything. They must first go to the studio at Condominio Records. One afternoon, Yosvel was at the studio talking to El Talent, the studio’s owner and New World’s producer. A reggaeton group came in to record. They brought boxed rum to drink and poured it into cups in the kitchen, laughing and gossiping. They wore knockoff Supreme streetwear.

There was about four or five of them, teenagers, cramped up in the single sofa. El Talent went over their background music, editing things here and there, repeating the same beats over and over. Everyone who wasn’t in this reggaeton group—Yosvel, El Talent, two other men, looked at them in amusement. They weren’t impressed.

El Talent makes a living producing songs for reggaeton artists. The genre is so easy to produce, he says. That’s why he does it.

He doesn’t like reggaeton.

“It’s bad music,” he said. “The lyrics are terrible.”

His passion is electronic music, but there isn’t a big electronic music scene in Havana. And so El Talent is confined to reggaeton, producing songs he doesn’t like, helping grow this musical phenomenon in Cuba.

Today, New World is the only rap group that El Talent works with. This wasn’t always the case but rappers have stopped rapping. Many of them have switched over to reggaeton. “Here it’s so easy to make reggaeton and find success,” said El Talent. “Here, anyone can do a song and it will be distributed and everyone will listen to it.”

El Talent’s studio is what is referred to in Cuba as a studio casero, a street studio. It exists outside the law. It is an underground business that the police have no interest in policing, as there are so many studio caseros here. His studio, like so many others, is perfect for urban music, for reggaeton. “Urban music isn’t trying to be high quality,” said El Talent. “That’s why there are so many studio caseros here. Urban music is pretty easy to record.”

El Talent built his studio behind the kitchen in his house on the outskirts of Havana. The studio is small and can barely fit all of New World inside it. There is a computer and a speaker and a microphone. Recording equipment usually comes into Cuba by way of Miami. Everyone here is related to or knows someone in Miami. People buy things on the outside and sell them on the island. Equipment is always used. You cannot find new things here. But they do the job.

The recording booth in the studio is tiny and can fit, at most, two people in a tight squeeze. Recording a song can take days because every instrument has to be recorded individually. No one can record at the same time.

El Talent began producing music when he was sixteen. He had friends who were rappers looking to record. He tracked down a small microphone and helped them. El Talent became more and more interested in the music world as the years progressed. He is thin and fair skinned, with dark hair, and he looks younger than his twenty-three years, but El Talent has learned how to make music, how to record it. He has learned that he can make a profit off of his passion.

He keeps updating his studio, fixing it up. He bought an air conditioner and got the acoustics just right. The ceiling is high, which is not good for reverb but he manages. There is no space for a drum kit. He would like to get more equipment, some keyboards so that he can record more live music and not have to use sounds from the computer. But he’s not at a loss for things, he said.

Sometimes El Talent works with foreigners, producing their music. Some artists come to Cuba and record in his studio. Others send him tracks to produce via the internet. But in Cuba there is no free access to the internet and El Talent must walk to an internet spot to download tracks. As the internet is slow, it can take a while.

But it is much cheaper for foreign artists to record or at least produce tracks in Cuba. Producers are expensive in America. “I have friends who tell me to go there because there’s a lot of money you can make,” said El Talent.

VIII.

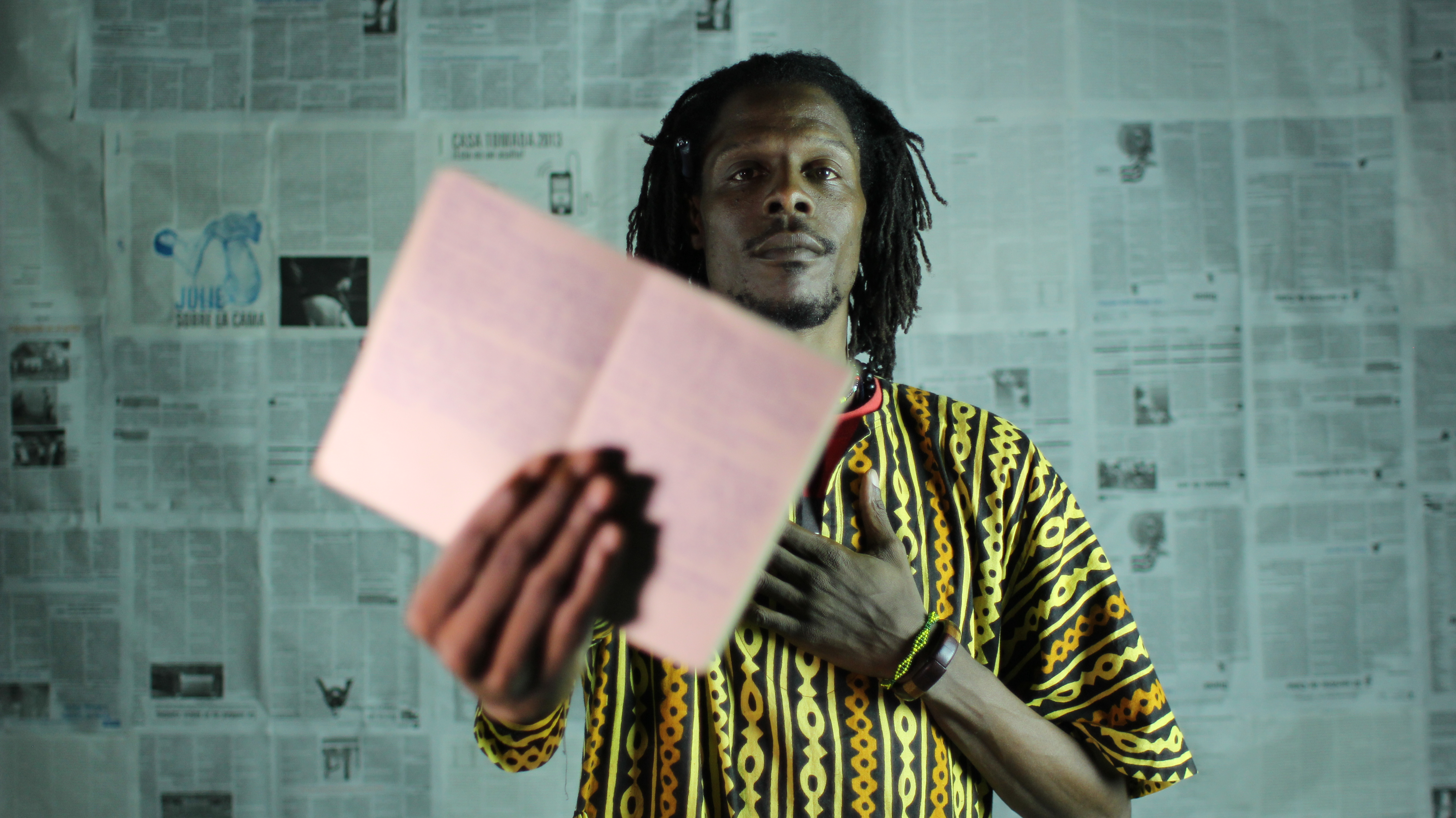

Amehel

Amehel is often referred to as the Snoop Dog of Cuba. Tall and thin, dark skinned, with shoulder-length twists, he bears an unquestionable resemblance to the famous American rapper. He is a spoken word artist, a rapper, someone who embraces all facets of hip hop culture—rap, breakdancing, graffiti. He has tattoos of Arabic characters and the continent of Africa on his chest and arm. He lives in Havana with his mother, where he likes to light incense and listen to R&B. He has a couch but he prefers to sit on the floor. Sometimes, he appears on national television, talking about his spoken word and performing his words, which are set often to slow and soothing melodies.

In my dreams, I have seen a crusade of broken hearts/The sound of a system that keeps you mute/That divides you/That keeps you mute.

In 2001, Amehel began to organize hip hop concerts and curate events. His goal was to get more women and foreigners involved in rap, and to establish festivals. He founded an organization called Union hip hop. But success wasn’t easy to achieve. “It seemed like people were either scared or had no confidence in the word ‘union,’” he said. Permission and funding for events were difficult to secure.

In 2008, Union hip hop had one international event. It was a way for Amehel to meet and connect with international artists. He wanted to do the event again, one decade later. But there was no support.

Amehel doesn’t belong to the Cuban Rap Agency. Over a year ago, he tried to get into it, showing a project he was working on. The man who spoke to him said they would call him back. He didn’t. “I knew he was lying to me,” said Amehel. “I knew he was never going to call me. He said, ‘I will call you soon.’ They didn’t call.”

In February 2018, Amehel began working on the Union hip hop program at la Fabrica de arte Cubano for a couple of months. Every Thursday there was a show in the Nave 1. Amehel brought in hip hop artists and groups, including New World. He would love to do more programs at Fabrica. But it isn’t up to him.

While most artists are against law 349, the majority keep their displeasure private. Amehel doesn’t. He recently signed a manifesto against it, in August 2018.

“It’s all about control, that’s why they have the law,” said Amehel. “They want more control. They have fear. They feel like something is slipping through their fingers. There are so many creative people in Cuba…They are making the path so much harder. They aren’t giving people many options.”

“They keep closing the doors even more,” Amehel said. “It’s crazy. It’s crazy. It’s control.”

Amehel, like most of his peers, is unsure of what the future holds for Cuban rap. It’s hard to find even some trace of success, no matter how hard you work or how talented you are. But there are a lot of people doing interesting things in rap, Amehel says, and “at least I feel good about the work I am doing.”

IX.

New World performing

Yosvel is nervous. It’s nearly 10 p.m. and there isn’t much of a crowd. New World has to go on at exactly 10 p.m. because at exactly 11 p.m. there are a couple of DJs performing in the large concert hall of La Fabrica de arte Cubano. People are waiting to dance to the top Latin hits of the moment. New World is performing on a smaller stage, and now waits in the room designated for the artists. They mix Havana Club with TuCola (Cuba’s version of Coca Cola), making Cuba Libres. Yosvel opens up a new bottle of rum. He pours some out on the ground and then pours a generous serving into his white cup.

Finally, someone introduces New World in the small concert space. New World begins to play and people wander in. In the front, a group of people, all friends and family and lovers of New World, go insane. Fists and phones are in the air. People jump up and down. They sing along to the songs. The songs vary. Some are reagge-ish, others more rock inspired, others more funky. Yosvel raps over all of them. That’s what Yosvel does—hip hop with something else.

There are two backup singers, one female and one male, one guitar player, one bass player, one percussionist, one dj/producer, and Yosvel. The hour goes by quickly.

New World stops playing at 11:04, four minutes behind schedule. They head back to the private room, wide smiles plastered across their faces. They hug each other, pour more drinks. They head off with different friends. They all have places to be, songs to dance to, drinks to drink. A woman, clearly a foreigner, asks the group’s manager if they sell CDs. The manager says yes; it’s 10 CUC. The woman likes the price. The manager pulls out a CD. It’s a burned CD. The woman rolls her eyes and walks away. She won’t pay 10 CUCs for a burned CD.

“I’m going to be super famous,” said Yosvel, a couple weeks after the concert at FAC. “It’s my dream that one day, people all over the world will listen to New World.”

Above this dream, Yosvel’s wish is to build a state-of-the-art recording studio in Cuba for street musicians, who wouldn’t normally have access to such a luxury, to record their music.

“There is so much talent in these streets,” Yosvel always says.

Above all, he wants a reality in which street musicians are able to record their music legally in Cuba, with all the instruments they need and good microphones and a good computer and a good producer. He wants to give a new world to artists who can’t have a new world, he explained.

“Dreams are difficult,” said Yosvel. “I just try to work and work and work and always with faith. Sometimes I lose my faith because it’s super difficult. I’ve been doing this since I was seven. It’s very hard. There are days when I have a lot of faith and I’m like, yes, I can do this. But there are days when I’m like, ‘Okay, I’m not going to be able to make it. I’m not going to be able to do what I want. Rap is in danger of extinction.’”

Yosvel sighed. “Please, how easy would it be to just do reggaeton?” he asked, to no one in particular. After a beat, he laughed. “I won’t ever make the switch. If I’m not a rapper then I don’t know what I am in this world.”

Every New World show begins with an introduction. Music surprises the crowd over loudspeakers and suddenly Yosvel’s voice begins:

“…I don’t know if you remember but they called me the progressive/We are the progress of the new generation/Without discussion/Look towards the future of society/Of humanity/This new chapter is called/My reality…Welcome to project New World.”

The group walks onstage. Yosvel dedicates most songs to his fellow citizens, to the people who keep their heads down and work hard, to the people from the cities and the towns. He sees them, he says.

Follow Natasha Rodriguez on Twitter.