This story was published in Issue 2: Silence.

This story was published in Issue 2: Silence.

Listen to a conversation about this story with author Selin Thomas and publisher Michael Shapiro on the Delacorte Review Podcast.

*

I was told by locals on the other side of the river not to travel alone through the backwoods. They said nothing was there but red road and red neck, and that since the ferry shut down there’s hardly a reason (if there’d ever been one) to cross over to that jagged slice of the county. I was going to investigate a century-and-a-quarter-gone lynching, an unpleasantness most locals had not heard about and would rather not discuss. In response to my inquiries, though, they spoke rude truths: last year—and wasn’t it awful—the Klan spray-painted epithet and insignia on road signs near the all-black intermediate school in Packer’s Bend, where I was heading.

“You’re going to think you’re in Beirut,” the librarian in nearby Monroeville, a mid-age white man, warned me about the county backwater to the west. “I’d be more afraid of the whites than the blacks.” My bloodline wears faintly on me so that it did not occur to him, as it often doesn’t, that this might already be the case, my having never ventured south until now and as a thing enduringly despised, too: the child of a black man and a white woman. Still, I took this and other local admonitions to mean that the people across the river were different, indeed backward, from the civilized rest of Monroe County, Alabama, where fear was old and black as the soil.

The land is a fraction of the 23 million acres the Creeks were forced to cede to the American government in 1814 after their final defeat at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, on the banks of the Tallapoosa River. Stashed arrowheads linger still in the dirt, surfaced without terrible effort. Monroe County was established as part of the resulting treaty and slouches from the state’s southern tier, distinguished by its piney woods and fertile soil—the black belt. Here, gently bent roads flanked by dogwoods connect forlorn towns and defunct pulpwood plants; cotton fields stretch into withering plantation houses, porches askew and vines like wraiths clawing them to the earth. Mangled oaks stand alone. It was a haunted place and that’s why I went.

a dilapidated house

Monroe’s county seat, Monroeville, is Harper Lee’s hometown and that of her singular American novel. Its only real attraction is the annual production of To Kill A Mockingbird that takes place on the courthouse steps every spring and draws small if international crowds. It’s a town built around a square of distinctly American character, bordered by a two-story library, a thrift store, a bank, two cafés and a restaurant, an oft-closed bookstore, a jail, an old Baptist cemetery, and a post office built during the New Deal. People still point out the old dry cleaners where Rhonda Morrison, an eighteen-year-old white female clerk, was shot to death in 1987. A black pulpwood worker, Walter McMillian, was framed by the county sheriff for her murder, tried for a day and a half and convicted despite alibi witnesses, who were black. He sat six years on death row before his exoneration. Upon his arrest, Sheriff Thomas Tate reportedly told McMillian, who was dating a white woman and whose son was married to one, “We’re going to keep all you niggers from running around with these white girls. I ought to take you off and hang you like we done that nigger in Mobile.”

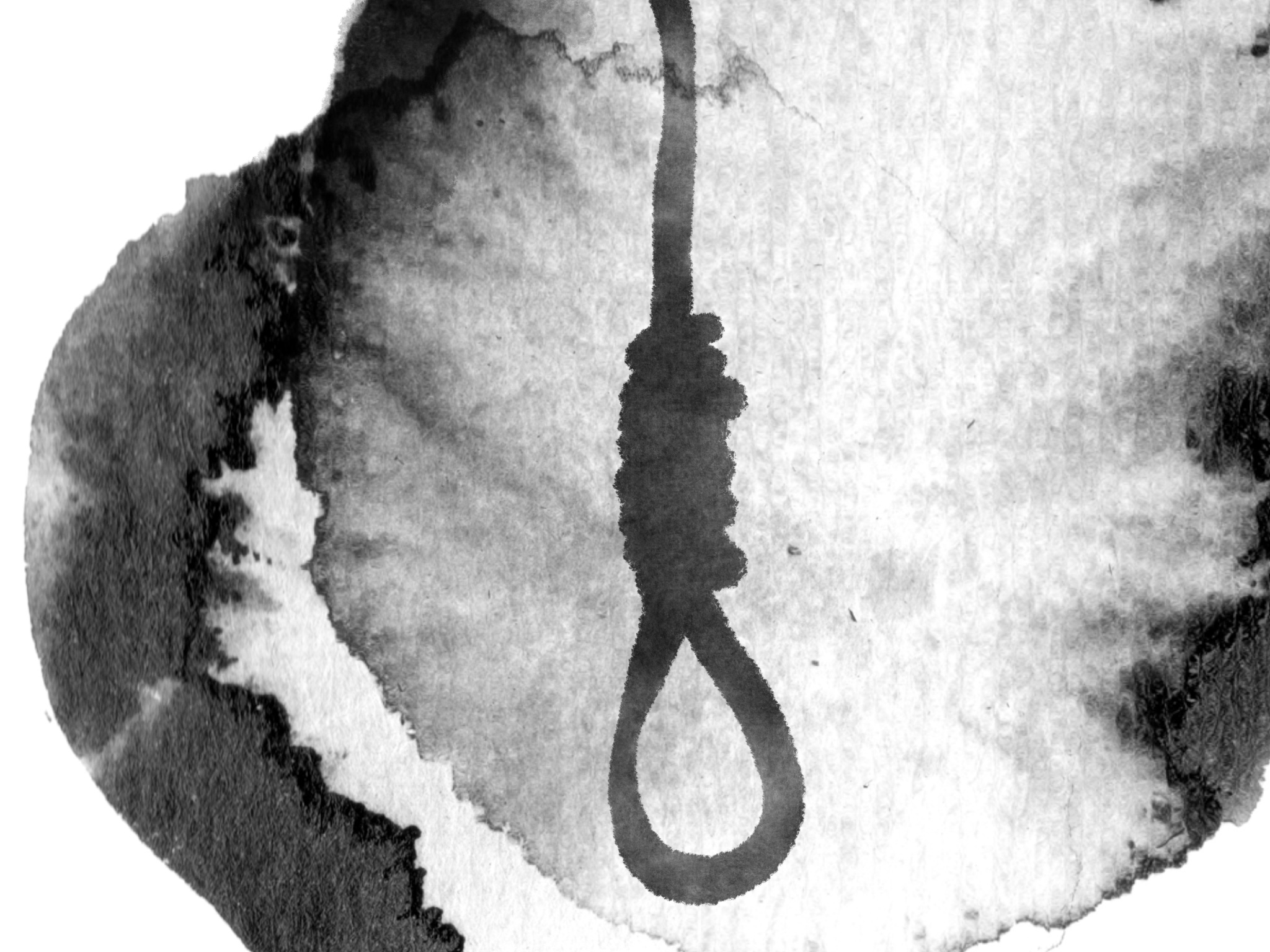

The sheriff was referring to Michael Donald, a nineteen-year-old who in 1981 was walking down the street when he was taken at random and lynched by the KKK after a mistrial was declared in the murder of a white police officer. The defendant had been black, and African Americans had been permitted to sit on the jury. After a cross was burned on the courthouse lawn, the men held Donald at gunpoint and drove him into the woods where he tried to run before he was caught, beaten and strangled with a rope. His throat was thrice cut before his body was hanged from a tree in a mixed-race neighborhood on Herndon Street, across from the house of Klan leader Bennie Jack Hays, who’d reportedly said, “If a black man can get away with killing a white man, we ought to be able to get away with killing a black man.” His son, Henry Hays, would burn in the electric chair for the Donald murder, in 1997.

Most everything in Monroe is quietly but insistently segregated, the reluctance of its locals in this arrangement feigned at best. “They keep to theirs, we keep to ours,” a black woman sighed. I saw people mix at a white-owned café in town where the owner calls everyone through the door “baby,” and at the county clerk’s office where the black women behind the counter shout “good morning” sincerely enough to make it so. No place else but the gas station. “Racism’s still here, it’s just quieter now,” said another.

The black schools used to be the white and are decaying from the inside out. The white schools, established to maintain the separation of the races after Brown v. Board, are private. A millennial graduate of Monroe Academy told me she’d read Mockingbird three times throughout her schooling; those I spoke to in the black community hadn’t. A white woman in her sixties recalled writing her takeaway on a back page: “The plight of the southern Negro.” Monroeville’s old courthouse, made famous by Atticus Finch in his defense of a black man, its fine domed clocktower the tallest building for miles, has been converted into a museum and gift shop through which a room is designated for the county genealogy. People come from across the state or region to sign their names in the visitor’s book and browse the records for evidence of their ancestors, a mostly white privilege.

On the wall are twelve family crests, the last names of the oldest property-owning families in the county. Nettles. Watson. Sessions. Given the former definition of property, these names unsurprisingly match those most ubiquitous on the county’s slave schedules and mulatto registers, recorded by federal census. Slave inhabitants were anonymously categorized, by number of, age, sex, color (‘B’ for black, ‘M’ for mulatto), fugitive status, manumission, and “Deaf & dumb, blind, insane, or idiotic.” Only the owner’s name is recorded, names that ring around town still, from black and white communities both, the legacy of mutual blood.

The ferry to Packer’s Bend, a single-car job, went out of commission years ago; the only way to the isolated backwater of the county is to cross the churning river by car, over bridges either thirty-three miles north or twenty-five miles south. The counties here weave in and out of one another, and much of the drive is northwest through neighboring Clarke County until the road thins and the dirt reddens as you approach the easterly river. I drove one gray morning out of Monroeville through the black neighborhood along Clauselle Road, its hot-houses quiet underground. Burnt Corn behind me and Scratch Ankle to my north, I came and went from Perdue Hill to Claiborne, crossed over the great river, and then remembered hearing the gravel in Bob Crawford’s octogenarian voice as he recalled Melvin Jones up on Highway 21 telling his parents if it was up to him they’d be sunk to the bottom of it with a 200-pound stone around their necks, for being “them sassy niggers.”

The road cut between fields of cotton in Gosport—its plantation houses conspicuously intact and turning their facades expectantly up at the sun—and I dared to imagine then slave hands between the brown, bare rows, their backs hunched or ripped or scarred, hot under their sacks, or swaddled tight with babies whose soft fat fingers would callous and bleed when they too learned to pick cotton, even in freedom. I smelled the rich pinewood mix with the wet clay as I drove north of Suggsville and up toward Packer’s Bend, the place of the old Johnson plantation and the scene of his murder, for which four men would swing between life and death without knowing which was the peace and which was the agony.

The highway road turned into county road turned into blood red, dead-ended local roads—Cat Mash, Full Moon, Black Jack—which were turning to mud now in the sun showers. The devil was beating his wife, the saying goes. The further east I went, the deeper the pine woods on either side; the fog floated the trees as if they emerged from purgatory. Biting flies like flying glass swarmed the air. Things were in ruins; a tireless car rusted, a gas station listed in abandon, and clapboard houses with ragged furniture still inside were collapsing into the landscape. I tiptoed in along termite-ridden planks for signs of life, but there were none. Their abandonment felt personal—a relative called on too rarely. Dead dogs lay along the road and there were great distances between seeing souls. When you did glance a lone figure, at a mailbox or on a set-back porch, it was only for a blink, a blur unto which one might assign history.

abandoned gas station

Packer’s Bend (originally “Packard’s” but melted down over generations on the Alabaman tongue) is within the Monroe County lines despite being over the river. Lower Peach Tree is to its north, Chance to its south. Land now owned by a family of timber farmers was, in 1892, a cotton plantation that would’ve bordered the black sharecropping communities here, then nearly three decades old. Its owner, named Johnson, with his young adult daughter were one morning that October found burnt black amid the ashes of their great home. They were identified by their jewelry. Two days later, a civilian posse took between six and ten black sharecroppers from the proximate community to the local magistrate, intent on their punishment. All were released but two. Dissatisfied, the mob returned the next day and imprisoned two more young black men. Before daylight the next morning, four days after the discovery of the Johnsons, it marched those four men—”none older than nineteen”—from the local jail and lynched them.

I went no further down the lane. Nothing remained of the Johnson place; no smoldering heap, no gold watch in the dirt, no grave, no marker. All that remained here of a forgotten history was what I could possibly imagine. They were fraught images—fractured—but they flashed before me in hot, hard shocks and played on the backs of my eyelids when they shut. Of indigenous rebellions and massacres, of rivers running with blood; of back doors and water fountains; migrations, Revivals, burning crosses, rotting fruit; of white teeth under black feet. Fearful images of fearful lives. What I could not conjure, though, haunted me more than the insidious landscape and its dark woods: the faces of four long-dead men.

***

Richard S. Johnson inherited the land from his father, Sherman, a native of Connecticut and “a negro trader in New Orleans” years before the war. The plantation he established on the Alabama River—slaves: 11—was sequestered to the Confederate Government during the war then taken up by his son upon his death. Richard, insolvent, moved his young family south from Massachusetts in 1886 or 1887. According to an account printed by the Montgomery Advertiser the week of his murder, his eldest daughter had married and moved to New York and his wife died shortly thereafter, leaving him and his youngest daughter alone in the big family house. Johnson was known among the locals, a neighbor told the paper, to prefer “the company of negroes to that of his kindly disposed neighbors. He visited about in the negro quarters and associated with them on terms of equality. Yet, the negroes all disliked him. He was quarrelsome and exacting with them. He had the reputation of not paying his debts and was oftentimes involved in altercations with them. That he should have gotten into a dispute with some negroes at his gate and been killed is not so strange.”

The night of Oct. 7, 1892, around 9 o’clock, Johnson was reportedly summoned to his gate and, after a brief altercation with two of the alleged perpetrators, slain by axe. Two more men were said to have kept lookout. In some press accounts, his daughter Jennie was said to have run out of the house to come to her father’s aid when she was killed. In others, she’s referred to as Johnnie or Jeanette, and was reportedly playing piano at the time of her death, one of the many inconsistencies of sensationalized reports of the time, the plantation having been more than 40 miles distant from a telegraph station.

The most local paper, The Monroe Journal, was then and is still out of Monroeville. It reported that the night fire’s “lurid glare” attracted the neighbors, who assumed the building was empty and had caught fire “through the carelessness of servants.” It burned until dawn, when a pool of blood and a tobacco pipe and signs of a dragged object were discovered a short distance from the scorched earth. Gold watches, currency and a quantity of costly jewelry were untouched in the house, “all of which goes to prove the motive of the crime was not robbery, but of a darker and more dastardly nature,” implied the front page story. “And as several hundred negroes live within a radius of a few miles, the natural conclusion was that some of them had committed the horrible deed.” By noon the next day, with several hundred townspeople gathered in anticipation, the hunt began.

The accused were many, narrowed down to four. The mob declared that a bloody axe, grey hairs on the butt, was found in the yard of Burrell Jones, who apparently lived nearest the Johnson place. He and a man who was possibly his brother, Moses, along with Handy Packer, Jim Packer, Moses Johnson “and several others” were arrested. The men were taken across the river to appear before a county magistrate, who released all on insufficient evidence but, allegedly, Moses Johnson and Jim Packer, who were committed without bail. The mob nearly executed them on the spot.

The two accused, it’s written, were delivered into the hands of guards and taken by a circuitous route to the Monroeville jail, today the sheriff’s office. Claiming stronger evidence the next day, civilians from the area rearrested and delivered to jail two more black men, named as Moses Jones and Handy Packer by some accounts. Now they were four.

The authorities claimed a full confession of the Johnson murders was made by Handy Packer that implicated himself and the three others, Moses Johnson, Jim Packer and Moses Jones, in the “dark and devilish plot.” A likely tortured, still lawless confession. Interviews with Moses Johnson and Jim Packer followed, said the authorities, in which the men also confessed, “their version agreeing in every important particular with that of Handy Packer.” Moses Jones, the fourth, “stoutly protested his innocence, but the other three charged him with performing the bloodiest part of the deed.”

News of the confession was said to have spread “like wildfire” and by Wednesday morning a mob of 200 men had gathered at the Monroeville jail. The Eufala Daily Times, reporting from the scene, claimed that when the morning mob began its destruction Sheriff J.D. Foster surrendered the keys and committed the men to their anarchic deaths. “The mob left for the scene of the crime with the prisoners,” the paper read simply, “where they will, in all probability, burn them this morning.”

But The Weekly Times-Star reported that of the two mobs hunting the accused, one bent on burning them, “the more merciful lot got them.” The Wilmington Messenger wrote the “fiendish perpetrators” were ceremoniously walked toward the scene of the crime, as the mob saw fit to punish them at the site of the Johnson plantation, but “too impatient for vengeance,” they halted about eight miles from the jail, three from Packer’s Bend. The doomed men were marched twenty feet more and, the paper claimed, executed with their hands tied behind their backs.

“Four Negroes Lynched,” read the headline in The New York Times on October 14, 1892. The article reported the men had confessed to murder and were taken by “a number of respectable citizens” and shot to death six miles east of the Alabama River. The Sumner County Standard reported, as did The Kansas City Star, that the young men were strung up then cut down, torn to pieces, returned to dust. News of the lynching reached even San Francisco, the Morning Call writing that the men were left dangling, twisting with the breeze.

By contrast, the local Monroe Journal decried “sensationalized reports” of the lynching in its follow-up edition, admonishing particularly the nearby Montgomery Journal for its “fertile imagination,” going on to state with plain venom that the bodies went unmutilated and upon inquest showed no evidence of any cruelty “more than was necessary to terminate their existence.”

No doubt was entertained. The story mourned the “quiet and peaceable Johnsons.” It closed: “While THE JOURNAL deprecates the circumstances under which it is considered necessary to anticipate the law in dealing with criminals, far be it from us, in view of the facts, to assert that the punishment in this instance was not deserved in the manner executed.”

Claims the men were shot while standing and left to rot seem generous, given the proclivities of racial terror in the 19th century American south and well into the 20th. Along with the Advertiser, The Weekly Times wrote that the four young men were lynched by rope, “and soon they were swinging between heaven and earth, and while yet living and struggling for breath their bodies were riddled with bullets. They were then cut down and their limbs torn apart by the maddened mob and then gathered together in a large heap and burned as they had burned the bodies of their helpless victims.”

The various reports and tallies differ in matters of utmost importance, including the names of the lynched and their ages, the cause for their arrests. Any record of their appearance before the law, or the alleged inquest; any record of their confessions or denials, their autopsies, or the location of their final resting place could not be found, if ever afforded. Consistent among the existing records, though, is the number. Four men were lynched in Monroeville in early October, 1892, the first recorded lynchings in a county which would see thirteen more before 1943 and several others in the decades after.

***

“We got a streak of segregation runnin’ through here that’s ‘bout as thick as cowhide,” Bob Crawford Jr. told me. He tapped a blanket beside him on the couch, his .38.

The Crawfords’ house is on the main highway road that runs through Beatrice, a sleepy isle of a town with delicate homes and a gas station and syrupy exclamations, such as that of a cashier lamenting over a dusty jar, his words tumbling out all at once, “Hot-dawg-the-price-a-peanut-butters-gone-up!” They live at the end of a semicircular dirt drive, off which a 1977 Ford rusts and their dog Blackie, who looks just as she sounds, emerges from her den to greet visitors. She’s not allowed inside.

Bob Crawford was born and raised in Drewry, Monroe County, 1931, and his wife Jessie was also born in the county, in 1934. They married in 1955 and together embody a storied southern grace. Bob laughs that his parents were “full-flushed Afro-Americans. They were one of those couples everyone was afraid of.” His father made something of a fortune bootlegging, for which he was imprisoned before setting up an independent timber farm. They were independent black home and landowners, ahead of their time, and ran a Movement safe house for voting rights activists here in the 1960s, practically a death sentence. Bob Jr., “Jun” as his parents called him, rotated shifts with his father on long, dark nights spent hiding in the thicket some feet from their porch, a shotgun at hand in anticipation of the Klan. His blue eyes shone with pride.

He recalled the lynchings and fire bombings and the long-lingering fear of violence that resulted from the battle for voting rights, which were federally won in 1965. Coretta Scott King was from neighboring Wilcox County, in which not one of its 6,085 black residents was registered to vote as 2,959 whites were, despite having only 2,647 white residents. That year, at the apex of the enfranchisement fight, Dr. King spoke in the driveway of Antioch Baptist Church, in Camden, to a crowd that would not fit in the church. In 1966, in front of that same driveway, thirty-two-year-old activist David Colston arrived with his family for a large civil rights meeting, driving a Chevy. Jim Reeves, a white famer, bumped his car, and when Colston got out to confront him Reeves shot him in the head at point blank range before his wife and son and church. “Shot him down like a dog,” said his widow Cassie.

Jessie changed the subject. She began to tell the story about her unlikely friendship with a wealthy white woman in town, causing her speech to quicken as her voice softened, her teeth gleaming from under her candy smooth and scented skin. The white lady, Mrs. Steele, had suffered through the loss of her husband and grandson in quick succession. After Jessie was first introduced to her while fundraising for Katrina victims, she found little ways to comfort the bereaved woman, who had lived as a stranger down the hill from her their entire lives. Jessie prayed with her at the gas station and dropped care baskets on her porch; they exchanged pies. “I didn’t go to the funerals because I didn’t want to make them uncomfortable,” she said. “We don’t visit one another’s houses or anything. Sometimes we talk on the phone.”

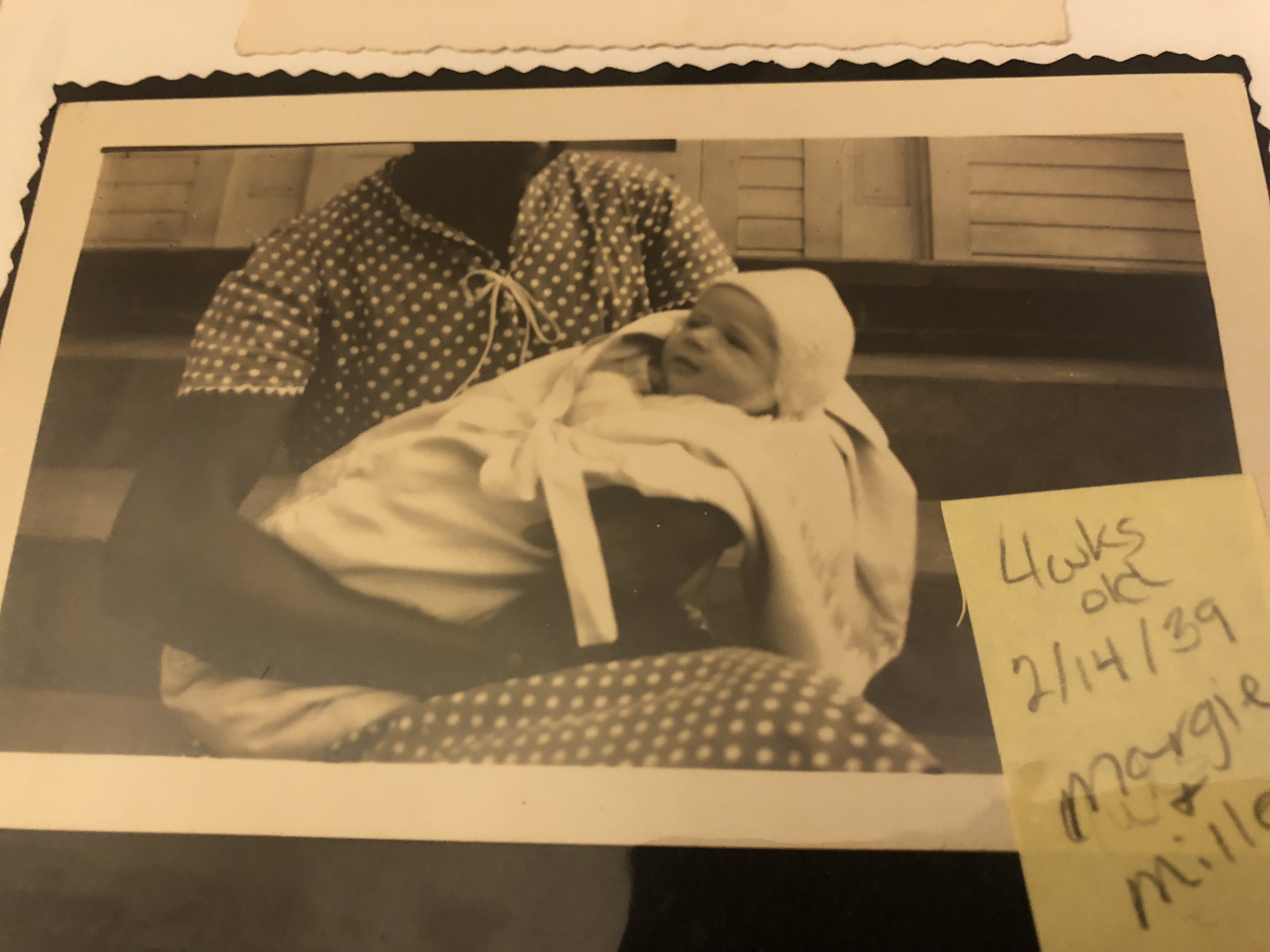

The Steele family produces lumber and sausage down the road, and kin of theirs is running for district attorney, her candidacy announced on wobbling wire yard signs along the highway. Jessie said she donated twenty-five dollars to her campaign because “at some point, we have to look at each other.” The Steeles own the Mary Elizabeth Stallworth House, named for its former lady. It has a long and wide front porch, fine antique furniture and a Daughters of the American Revolution certificate framed on the wall, dated 1984. The Steeles operate the house now as a bed and breakfast, and it’s where I was staying, at the end of Beatrice’s only commercial road. Framed in the living room are aged photos, including of a young, slim Mary Elizabeth standing mid-conversation beside a sharply cut black man of ochre skin and about her age. Another is of a stout black woman on the house’s porch steps, staring stiffly out of the frame. This woman was seen throughout the family albums, this time standing in the sun by a field, her eyes and lips still dark and hard. Beside it a yellow post-it note was labeled “Mary Sawyer.” A few pages later, among some photos of baby “Margie” in the arms of her mother, dated 1939, there is one of the white baby girl swaddled in more white, looking out from the firm black arms of a woman in a polka-dot dress, though the photo only just reaches her neck.

Margie

“You don’t go telling those people down there who you are,” Bob said. “Keep your poise, but don’t you tell them who you are. Stone bone rednecks, baby, and don’t you forget it.”

***

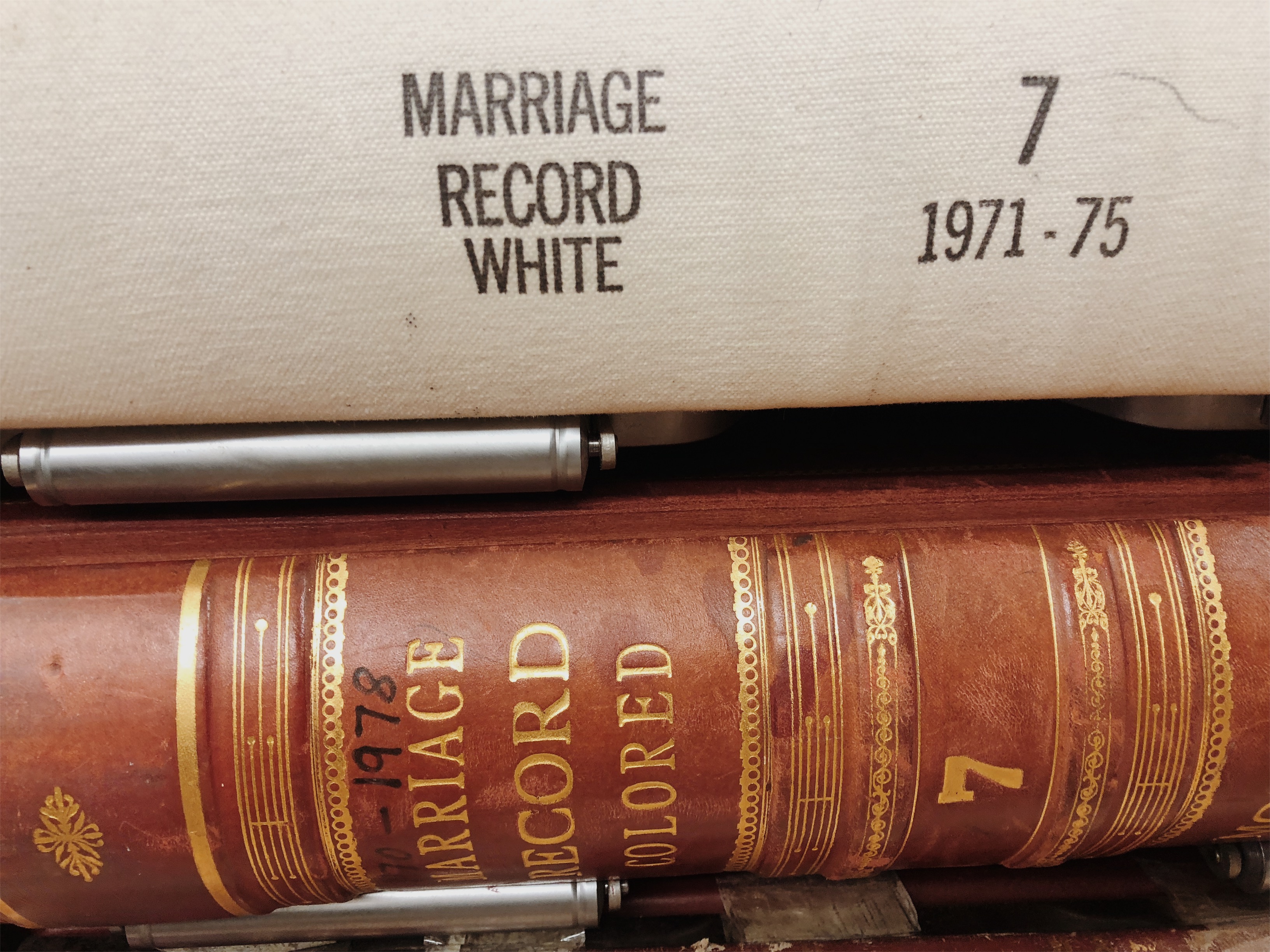

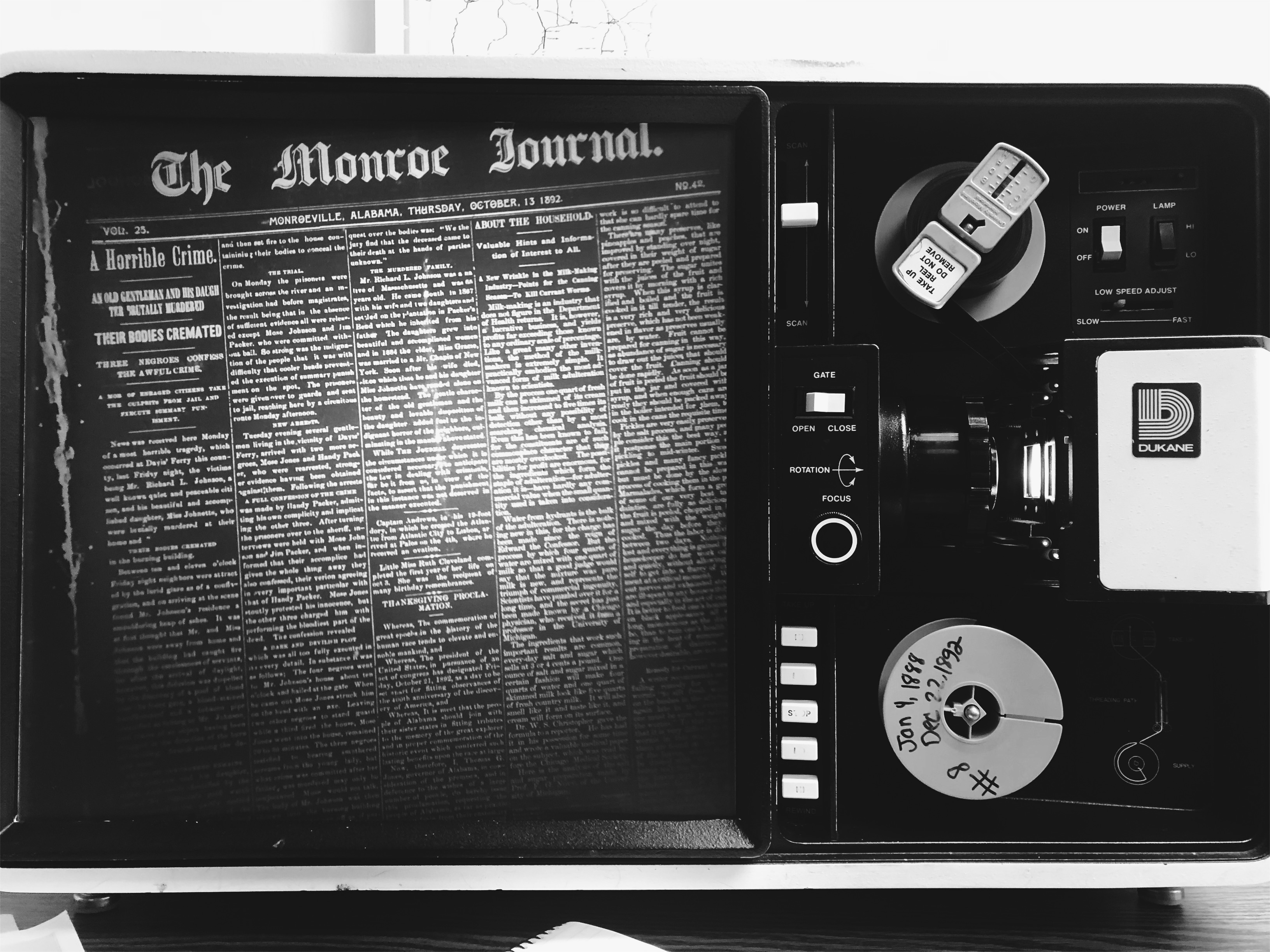

I flipped gingerly through that year’s original copy of the Monroe Journal in the courthouse basement. Despite his gentle irritation at my archival requests, the genealogist finally led me through a thick metal door, down littered steps, and left me alone with a pair of white gloves and what he called “our treasures.” I scoured rows of metal shelves and the countless boxes on them reaching to the ceiling, looking for evidence of four men. Among a century’s worth of mortgage and marriage record books (labeled “white” and “colored” well into the 1980’s), chancery court appearance cards, jailhouse journals, civil settlements, faded red-leather bound tax and bankruptcy books, there wasn’t a trace of them.

Marriage Records

I slid a thin, gray rectangular box labeled “Monroe Journal 1891-1892” from a shelf. Atlas-sized and one-hundred-twenty-seven-years old, the edges of 1891 crumbled at my touch. I turned through 1892, past undertaker and dry goods advertisements, land register notices, sheriff’s sales, and the serial fiction that once made up front-pages. There is a description printed of an advanced cotton-harvesting machine: “…two men and a single team are required. It will harvest from 5,000 to 6,000 pounds of cotton per day at a cost of $3 to $4, as against forty men picking not over 150 pounds each per day at a cost of $30. This machine is so simple as to hardly require an explanation.” There was something about the committee of the Democratic caucus meeting in New York, at the Fifth Avenue Hotel at 10 o’clock, to ride a carriage to the residence of ex-Secretary Whitney. “Details of what transpired are kept a profound secret.” Under an all-capitalized headline “THE EXODUSTERS.” read news about the agitation of the colored population in Kansas, where a movement “to solve the negro problem” by a gradual system of immigration to Central and South America was being revived. President Brown of the Kansas Freedman’s Relief Association said the exodus would start when the full advantages of life in Brazil became known, and the population had been assured they could get a rate of $10 for transportation, $2 per head on the Mississippi River “from any point below St. Louis to New Orleans” and from there to Brazil by boat, for $8. I slowed as I reached October.

Finally, the front page of the second week of that month, 1892. One week after the October 7 murder of the Johnsons, the headline read:

“A Horrible Crime. AN OLD GENTLEMAN AND HIS DAUGHTER BRUTALLY MURDERED. THEIR BODIES CREMATED. THREE NEGROES CONFESS TO AWFUL CRIME. A MOB OF ENRAGED CITIZENS TAKE THE CULPRITS FROM THE JAIL AND EXECUTE SUMMARY JUDGEMENT.”

The Monroe Journal

I flipped on to look for a follow-up. Q. Salter’s editor’s column the next week read: “We learn that some hot-headed colored people living in the neighborhood of where the Johnson murderers were executed, held a meeting recently and passed same [sic] very incendiary resolutions,” a lynchable offense, “in which they threatened to take the lives of every white man who had anything to do with mobbing the negroes.” The black community was organizing. “The ring leadership,” the editor warned, “… are known and their movements watched.” The Weekly Times Star, out of Kansas, reported that week that “the greatest indignation prevails in the community of Davis Landing, where the crime was committed, and it is said that the whites threaten to exterminate the whole negro population.”

Two weeks later, the Journal printed a reply under an ad “For palpitation of Heart, Dr. Miles’ Heart Cure.” The dateline is Nov. 10, Bell’s Landing, the locale of the nearest telegraph station to Packer’s Bend. It’s signed “Prof. F.J. Marshall (col).,” and reads: “Will say the colored people of this community are very well satisfied with the fate those boys met with, and no meetings of indignation has been held. They are too glad to get rid of such worthless, dangerous characters as they were, for no human eye ever beheld such an atrocious crime as that one was.” It concludes that the colored citizens were as eager to catch the guilty as the whites, adding readily, “and about meetings of indignation being held is all a mistake.” Given his title, Marshall was likely a leader in the community and it’s plausible he was on a mission to prevent more lynching by reassuring the white citizens of Monroe that the black community wasn’t incensed. Perhaps he had another motive. It stands to reason that they were indeed reeling with despair and anger, possibly considering vengeance for the murder of four young men from their community, two of them potentially from the same family.

***

Up the road from the Crawford’s, New Purchase Methodist sits at the top bend of Beatrice’s only hill. I went on a thick, dark Sunday morning and was welcomed first by the solemn words on the marquee outside—“Whosoever will, let them come”— and then with reasonable suspicion by the only man yet inside, who’d just swung open the back door and was running home for his teeth. On the wall in the back room, the Obama family beamed opposite a motto overhead: “When all is said and done, more will be said than done.”

It turned out the marquee alluded to a difficult reality facing the 118-year-old black church, struggling to fill its pews; fewer than a dozen worshippers trickled in. The good books were beat, the choir spare. And though congregants addressed each other familiarly, as Miss Mabellean, or Miss Minnie, some spoke not at all. Brother Prevo, a Vietnam veteran, recalled coming home from war unable to vote. He was the county’s first black deputy sheriff in the 70s, he recalled with a single knowing chuckle, “when they decided they needed some black folks in there.”

The Reverend Dr. E. Elaine Crittenden gave a sermon about living in the light, and fixed on the church’s need to adapt to the times, to grow by welcoming even white people, and gay people. “Don’t let the darkness of others come into your spirit,” she boomed. Her congregation replied with throaty affirmation. “We must be accountable.” She intoned that evil begets evil before reciting John 3:14, about Moses lifting the serpent. The choir called out and was answered. The carpet balled, the lights flickered yellow and collection baskets were circulated; the pastor handed a hunched man an envelope at the altar, saying only, “You are not alone.”

At mention of the 1892 lynching, a black congregant said, “Some things we don’t want to remember,” her eyes fixed sharply at the ground. She looked up, hesitating, a fresh anger coming off her. “But that don’t mean it goes away.” The reverend said, “If you look at our history, we should not be here. There is no shame is talking about what happened. We need to talk about our history in order not to go there again.” She ended, “What’s done in the dark will come to the light.”

Once everyone had gone, the electric bill was tallied and paid, the lights turned off and doors locked, I left with Miss Mabellean Nettles, a choir singer and church leader. We ate fried chicken out of Styrofoam boxes on the mahogany dining table in the Stallworth house, which she called “Miss Lizbeth’s.” Miss Mabel has worked for the Steeles as a housekeeper and nanny for thirty-two years, since between the births of their two sons, now grown and with children of their own. They are good people, she said. She pointed to a grief-stricken apology she received from the younger Mrs. Steele after an old white cattle farmer in the big house down the road called her the slur as she was helping with an event in his house. “I was just about fixing to get in my car and go” when Mrs. Steele apologized in his place, she said. “I stayed.” That wealthy cattle farmer is dead now, though his son, in his seventies, lives in the big house down the road. His broad-brimmed hat label reads, “Like hell it’s yours!” and among the family photos in their grand hallway he proudly pointed to one of his daughters on either side of Jeff Sessions, who’s from down the road. As I discussed with his wife my plans to visit the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, where an annual commemoration of Bloody Sunday had just been held, he’d said, “Did they get the hoses out?”

***

The Monroeville librarian was intrigued if also wary of my investigation, and took it upon himself to represent to me the more kindly aspects of Alabama, and Monroe in particular, of which there are fairly plenty. In so doing, however, he did by turns contradict his own best intentions, demonstrating instead, and rather precisely, prejudice’s sinister nature and its insipid defense. Despite his genuine cordiality, a consequence perhaps of my gender or color, he’d recalled with marked tinges of both pride and regret that his family had not been wealthy enough to be slave owners. He’d also assailed whomever came here to research the 1892 lynching on behalf of the Equal Justice Initiative, which had been conducting research for the national memorial. Apparently, this young black northern fellow had left behind a copy of his report, antagonizing the librarian into further inquiry. By the time I arrived to look into the 125-year-old past, some of his opinion on the matter had been informed by local lore, traces of the country’s pernicious racial thread which, if followed, can be found woven meaningfully into every event it has already and will ever endure.

“The subject of your search marks a time in Alabama (and elsewhere) that our beautiful state cannot and should not abide,” he wrote genially enough by email. “The people here have been marked by such experiences and that is truly unfortunate.” Citing his years-long work researching southwest Alabama’s “infamous” events, he continued, “The proof is not scientific, however, most crimes were as it is today: blacks killed blacks over women and whites killed whites over land or possessions,” a telling distortion of both race and violence. He went on, as if anticipating that last aside, “The savagery of white on black was as common as black on white. The hysteria created when a white woman was killed by black men cannot be overstated.” He had one point there, then he muddled it. “In the [Johnston] case, local stories imply that [Hardy] Packer, a light-skinned mulatto, some say more white than black, became enraged when Miss [Johnston] resisted his romantic interest. Is this true? Without any proof, the answer is no.” His desire for it to be true was then impressed upon me, as he’d started with claiming, by his own admission, a glaring oxymoron: unscientific proof. Then came the common refrain of sinister black male sexuality praying on innocent white female flesh, buoyed by the total speculation that Handy was light-skinned, implying he would act above his station—uppity. The librarian finally gave himself away entirely by ending with a not-unreasonable sympathy for the Johnsons: “One should question the brutality inflicted upon Miss [Johnston] and her father. There was some deep seated passion that would cause a group to kill as the father and daughter were killed.”

What is unreasonable is this contemporary white man’s facile grasp of America’s racial reality, a gaping inadequacy that extends far beyond the south. His comments were not unkind on their face but they belied a cruel fear–a fear of black people that ensures fear of white–that has passed so thoroughly through us as to alter our national character; the education, incarceration, life expectancy and poverty rates; the incidence and deadliness of diabetes, high blood pressure, breast cancer, and maternal and infant mortality; voting rights, political representation, and power. So when the librarian attempted to identify “some deep seated passion,” he was unable to name plain, historical rage, and instead sexualized it. And when he attempted to appropriate truth’s nature by pleasantly disregarding my–a northerner’s–pursuit of the brutal past, he failed to see the value in the subjectivity of truth. This is because what he values is what he believes and what he believes is who he is. He could not know and he could not be told the elusive truth, for his identity is borne by a historical tension that nags toothlessly at him and which he cannot articulate, for he is reluctant to discover what it will mean he owes, and to whom.

***

“It is with no pleasure that I have dipped my hands in the corruption here exposed,” wrote Ida B. Wells in her anti-lynching treatise Southern Horrors, in 1892. The preface is dated Oct. 26, 1892, fourteen days after the lynching of the Monroeville four. They are therefore mentioned on the very last page of the pamphlet, which enumerates lynch law and names the pernicious mechanisms of racial terror in the south that survive well into the next centuries. She wrote of the four’s lynching: “The suggestion of the whites is that brutal lust was the incentive,” leading to the inevitable conclusion that a black man or men in close proximity were the perpetrators of the awful crime. Her account, which refers to an unnamed report, says Jeanette was “outraged,” or raped, and that none of the four men were more than 25 years old. She names the lynched as Berrell Jones, Moses Johnson, Jim and John Packer—slight variations from the Tuskegee and NAACP records—and reports they were burned while yet alive.

Of the 4,743 American lynchings that were recorded between 1882 and 1968, black people accounted for 3,446, according to the NAACP. The reports are vague, sometimes nameless, and commonly indicate that more than 4,000 black people were publicly, or spectacularly, murdered over a shorter period. More surely lost to oblivion. Black people (fifty women between 1889 and 1918) were lynched on vague, often creative, charges: incitement, robbery, “alleged arson,” passing counterfeit money; insulting a woman, scaring a white child, “For making unruly remarks,” or mistaken identity. Hung up, shot up, burned alive, castrated, butchered and passed around, sold for parts as souvenir. Killed even after they were already dead.

It is important to note that the lynching of black persons increased dramatically after the Civil War. Though white and Native, Latino, and Asian people were victims of this national lawlessness too, by 1892 the majority were black and their deaths concentrated on southern soil. The year of the Monroeville four, Wells recorded a 200 percent increase over the preceding decade; 241 men, women and children across twenty-six states were lynched that year, 160 of them African-American compared to fifty-two in 1882. Her data indicate a 43 percent increase in the total number of African American lynchings over two decades, from 1882 to 1910, “with seven of the eleven years showing rates above 90 percent.”

This shift in the post-Reconstruction south is distinct. Before the Civil War, the lynching of black people was antithetical to ownership of them; it was much more profitable to sell your property than kill it. But by the time President Rutherford B. Hayes removed the last federal troops from the south in 1887, Reconstruction resembled anarchy and white southern lynchers had determined the national law to be futile, opposed to the natural order, and requiring the preservation of civilization as they saw fit. Which is to say, the necessity to protect their women and swiftly punish the black mongrel seeking equality with the white man. This malevolence bound, rather effectively, the threat of brutal death to the already fraught struggle for black enfranchisement, civil liberty, and an economic base, or the progress expected after emancipation and the victory of the north, still commonly referred to with disdain in these parts. Much like the Nuremburg laws of the early 1930s, racial power in the American south was codified first by provisional rules, the Black Codes, before institutionalized white control over black lives was cemented. Jim Crow law earnestly maintained white supremacy until the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, though its legacy remains healthy.

Alabama alone carried out a total of 273 lynchings in the half century after 1871, according to the imperfect tally of the Tuskegee report, a lynching survey through to 1920 that serves as a reminder of the unreliability of lynching records. Never complete, these tallies are intended to obscure the humanity of the victims, and the mobs that took them, so inquiring into the scrolls is like picking a scab to ensure the scar, to forbid the customary erasure that has so marked the American character. That has so corrupted it.

The year of the Monroeville lynchings, 241 persons were lynched, twenty-two in Alabama, fourth in number behind Arkansas (twenty-five), Louisiana (twenty-nine), and Tennessee (twenty-eight). Fifty-seven of these charges were rape or attempted rape. Fifty-eight were murder; the rest vary at much smaller numbers, from rioting to self-defense, insulting women, “desperadoes,” no cause given, and “no offense stated, boy and girl, 2.” In Monroe before 1950, according to statistics compiled by the Equal Justice Initiative, a total of seventeen lynchings were carried out.

Alabama led the nation in the number of lynchings in 1893, with twenty-five. Of the 159 total lynchings that year, fifty-two, or nearly a third, were committed on charges of rape, attempted rape, alleged rape, or suspicion of rape, making that year emblematic of racial terror statistics. Over a twenty year period, 1900 to 1920, as tallied in the Tuskegee report, more than a third of total people lynched were charged with rape.

“The Southern white man says that it is impossible for a voluntary alliance to exist between a white woman and a colored man, and therefore, the fact of an alliance is a proof of force,” wrote Wells, who was among the first to reason, statistically, historically and biologically, against the vilification of the black man as a sexual predator. These encoded, gendered racial stereotypes persist in the national psyche; my father was six before anti-miscegenation laws were federally struck down. “Nobody in this section of the country believes the old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women,” Wells went on. “If Southern white men are not careful, they will overreach themselves and public sentiment will have a reaction; a conclusion will then be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.”

She cites several cases in the assertion that “there are many white women in the South who would marry colored men if such an act would not place them at once beyond the pale of society and within the clutches of the law. The miscegenation laws of the South only operate against the legitimate union of the races; they leave the white man free to seduce all the colored girls he can, but it is death to the colored man who yields to the force and advances of a similar attraction in white women.” There are accounts in Alabama and South Carolina of farmer’s wives giving birth to black babies, and farm hands taking the mules they’re working to flee upon hearing the news. Wells cites the case of a wife of a practicing physician in Memphis who ran away with her black coachman, and whose husband tracked her within a month and brought her home; “The coachman could not be found.” In the case of Sarah Clark, also of Memphis, the defendant loved a black man and lived with him openly. When she was indicted for miscegenation, she swore in court that she was not a white woman.

“The race thus outraged must find out the facts of this awful hurling of men into eternity on supposition, and give them to the indifferent and apathetic country,” Wells wrote of the national horrors she was recording. “We feel this to be a garbled report, but how can we prove it?”

***

I wanted to get as close as I could to the four men’s dying place. The Monroe Journal account states the mob was heading to the Johnson plantation, the scene of the murder, with its four prisoners. But at “Graham’s Bridge over Flat Creek,” their patience gave out and the men were marched twenty feet more up the road and executed. The bridge no longer exists, but a map from 1916 shows it was located in locale 161-NW, which today is Section 31, Township 8N, Range 9E. It was nondescript now as it was nondescript then. Flat Creek. Just as it sounds. The bridge was long gone but I drove and got out, enveloped by the hot, unmoving air, and stood about there. One and a half miles north from the center of Fountain—a town so rural it’s better described as a wood—I looked twenty yards up the road.

From where I stood, I imagined that they hanged four men’s bodies from that tree, there. I imagined a fiery mob in the cloak of night come to separate these and many men from their lives, laws be damned. I thought of the four mens’ feet, side by side, for I didn’t know their faces. I thought wincingly then of my father’s and his father’s feet, turning with the breeze at the end of a rope, for love. I willed myself not to look up further, to faces I knew well, and was unsuccessful. I thought of Dr. King speaking of bootless men. More feet. And as I drove off, drenched by a dank rain and spooked by the nameless tree I’d cursed, I heard Reverend Crittenden citing Luke in her measured, iron certainty: “What you do in the dark will come to light.”

***

I went to Montgomery to see the new lynching memorial, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the first of its kind in the country. I was to accompany a woman, Annie Charlie Whitlock, whose father was lynched in Monroe County, in 1954. Across the street from the immense outdoor site, memorializing the more than 4,400 lynching victims in America between 1877 and 1950, a smaller memorial was being commemorated. On it, the names of 24 men and women who were lynched in America between 1950 and 1959.

On May 7, 1954, in Vredenburg, Alabama, Russell Charley was lynched. He was a father of seven. When he hadn’t returned from work in the morning, Charley’s oldest sons, sixteen, fourteen and twelve years old, began an increasingly desperate search for their father. They found him hanging from a tree in a nearby wood and were made to cut his body from the branch on which he hanged. Annie Charley, nearly five years old then, was digging in the dirt outside of the house when her brother Willie came running. “He stopped but couldn’t say nothing, then he ran and got mama,” she recalled. Her pregnant mother ran out of the house with Willie and her youngest son, Ernest, who was seven. She forbade Annie and her older sister Mildred from coming.

“My brothers were never the same,” Annie, now 69, told me. “Ernest never got the blue color out of his mind, the blue color of my father’s face and his eyes. It punished him.” No one was ever held accountable for Charley’s death.

At the entrance, Annie was impelled to touch the iron hand of the naked female sculpture who was chained at her neck, waist, and feet. She held a baby in one arm while her other was reaching out and falling short of a similarly chained man with his back to her. Around her were four other life-size figures in various states of movement, people in chains, rusting. The Whitlocks walked arm in arm up the outdoor path, and Charles Whitlock said to his wife: “Do what you have to do. I never experienced this, but you did. The reparations are coming. See how God works?” In fifty years of marriage, Charles had never heard the full account of his father-in-law’s death, or its lingering visions, until now. Annie slowed to cry.

“They don’t just do it to one person,” she’d said of her father’s lynching. “They did it to all of us.”

The pathway leads to rows of inscribed copper monuments which are first eye-level before they progressively ascend to ten or twelve feet, hanging awesomely overhead, their names becoming indistinguishable. At the ultimate end of the memorial pathway, past Toni Morrison’s words on the wall (“…And O my people, out yonder, hear me, they do not love your neck unnoosed and straight. So love your neck; put a hand on it, grace it, stroke it and hold it up…”), there lie flat duplicates of the hanging copper monuments, twins to each within the memorial. They wait to be reclaimed by the counties they represent, which must apply to have them erected on their soil and which will be known by their presence here should they fail to meet that obligation.

As we left the memorial, several boys wearing the navy blue uniform of an academy in Mississippi were entering, and caught Charles’s eye. He abruptly stopped and spoke to them on the pathway in front of the statue of slaves: “Boys, you take care of one another. If you get angry, you walk away, just walk away. How old are you? That’s right. Don’t get angry. You help one another out, boys, pull one another up.” They nodded and said “Yes, sir, yes, sir.” They were thirteen and fourteen years old. Annie pointed to her white shirt, her father’s name and the date and place of his death printed on it in red. “My daddy’s memorial is across the street.” The boys did not know, exactly, what she meant but their eyes flickered from polite unknowing to staggering recognition within a few seconds. They straightened their shoulders and extended their hands to be shaken as they asked this elder couple their names. The young men told them they were visiting from school and this prompted Charles to say to Annie that they needed to organize a church trip. In place of the usual farewells of a stranger who has just seen what one is about to, Annie said knowingly, “Hold your necks high.”

Annie’s father’s name is displayed among others whose relatives and representatives, some old, others young, had come to lay flowers at their etchings. Harriette and Harry Moore, husband and wife, registered over 3,000 black voters in Mims, Florida, for which their house was bombed on December 25, 1951, killing both. Isadore Banks, a WWI-veteran and landowner, was chained to a tree and burned on June 5, 1954, in Marion, Alabama. Due to his mother’s sheer will, we know what happened to Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi on August 28, 1955, here recorded. That same year, Reverend George W. Lee, who was the first black person to vote in Mississippi’s Humphreys County since Reconstruction, was shot and killed while driving home. The sheriff claimed the lead bullets found in his jaw were dental fillings.

Twenty-two-year-old Hilliard Brooks Jr. was shot by a white police officer in 1950 for refusing to reenter a bus by the back door; Lamar Smith was shot in 1955 on the courthouse lawn in Brookhaven, Mississippi for encouraging local blacks to vote; and Dr. Thomas Brewer, a 72-year-old physician and voting activist was shot seven times in 1956 by a white store owner claiming self-defense. In 1958, 30-year-old Richard Lillard was beaten to death in a padded cell by three white police officers in Nashville, Tennessee. Mack Charles Parker, in April of 1959, was shot twice, bound and dumped into Mississippi’s Pearl River for assaulting a white woman who fabricated the accusation to hide an affair with another man. William Person, in June of that year, was shot by a white man while running away. No one was ever punished for these crimes, even if they’d confessed. The victims’ names were read, their brief biographies given. A soprano sang a verse from Matthew, “Speak the words and you will be healed,” and grandchildren were there to hear it. For the first time in many of these people’s lives, their pain and fear, no longer a matter of survival, was exposed and laid bare. Instead and at last, an awesome grief was expressed, brutal injustice confronted, people long-dead memorialized by the still-living. A line formed to shake the hand of Hilliard Brooks’ 91-year-old widow, Estelle, who’d been pregnant with their third child at the time of his death and stood here on the arm of her oldest son.

I suppose those bodies were meant to rot on those trees and their distraught relatives were meant to collect at their limp feet, read the warnings on their backs, and heed them in perpetuity, for the cutting down of fathers and sons from trees should be incentive enough to stay down. Time and again, of course, it was; it is; has to be. Families fled in the black of night, enough of them to mark a great migration. Names and histories were left behind, blown from memory, burned down. Tongues lost the language of this particular terror, its descendants grew up knowing another kind of survival.

And now enough time has passed that Anne Charley Whitlock has distance and courage enough to conjure up the death of her father, to herself and her family, to other living descendants of lynchings, and to a stranger who asks. Enough time has passed that one can and must use her imagination to trace the anger back whence it came. Two or four black teenagers, impulsive though they may’ve been, were impelled in 1892 Alabama to kill a white cotton farmer and his girl with an axe and light them up in their plantation house with the gold still on their bodies. It has been long enough that it isn’t difficult to allow that their murder was nothing less than the cry of war, and time enough too to hear it as righteous. The lynched can be now named, honored along with a rage that has been clawing through for centuries and is finally, specifically spoken.

It’s true that very little time has passed since the hurling oceans and the hold, the islands, their sugar and their receding shores; since the chipping plantations, the blows and auctions, and the lynchings. It’s also true that people have long found ways to meet their pain and the fear they were born into and die with, and so it is not specific to our time or land. What is specific is the story of this people, for none in history strode their path by the hard-wrought identity which informed it. Here, our time and land has aged just enough that one might now look yearningly, fearfully back. When she does, for it is her time and her land, she will find not merely terror, but carefully guarded shafts of light.

Among the first few counties etched in the copper plates—their dimensions akin to a coffin—along the outdoor pathway at the national memorial is Monroe. The first four etchings list Burrell Jones, Jim Packard, Moses Jones, and Unnamed. The date, “10.12.1892,” gapes indelibly under each of them. Thirteen more are remembered below them and countless thousands on the pathway ahead and above, the named and nameless. It is unlikely their lives will ever be fully known, but their deaths are here forever fixed.

Follow Selin Thomas on Twitter.