This story was published in Issue 1: Home.

Listen to a conversation about this story with author Diego Courchay and publisher Michael Shapiro on the Delacorte Review Podcast.

*

PROLOGUE

Two weeks before I went to visit him, my father set his hillside on fire. It began as a harmless clearing of weeds, turned out of control by drought and a broken hose. Now, on his isolated mound, scorched earth stood out like ink on a page. It showed the fire’s progression in a winding semicircle around the house, having turned trees ocher as if by an early autumn. He had fought it alone, with a bucket, dozens of loads sizzling on advancing flames. It was still spreading as he threw the last of twenty gallons from the barrels of rainwater left from spring. And just as there was nothing left to do but wait and watch it burn, he saw the lights on firefighters’ helmets, their trucks driving up the dusty road.

From atop his house, the landscape of forests and fields appears devoid of other homes, yet someone miles away had seen the smoke and called for help. It had not occurred to him to do so. In the end it was disaster averted; he escaped unscathed to tell the story, yet another tall tale about the crazy old writer cooped up in the middle of nowhere. People told him he was an idiot.

He told them that this is how life works: You get saved at the last minute and you go from tragedy to farce. That’s how it went in the war.

The house where he lives on the hill was an abandoned sheep pen, perhaps more than a century old, until a sailor stranded himself on that arid land, and remade the house into a home with no ocean in sight. Jean Claude Courchay, my father, moved into the house some months after the sailor’s death. He’s another castaway with a seafaring past, who did his military service on the aircraft carrier La Romanche. Maybe somewhere in there is a common experience to explain the choice of home: two men who loved the sea retiring among the rocks.

The house in the hills.

The house is at the end of a dirt road on hunting grounds for boar, deer, and pheasant; winter buries it in snow, which melts and freezes the road into an icy slide that will discourage any car’s descent. Until spring arrives, you can be isolated save for long excursions on foot or tractor. It’s prime real estate to see the world recede into forgetting. A telling place, it speaks in its distance from all else, in age-old wooden beams and peace. But only if you can withstand the nights: those moments when you could believe you’re the last person left on earth. My father had spent a long time looking for just that.

His home is a curious full stop for a lifelong wanderer. Then again, in traveling you must allow for your soul to catch up with you, as a wise woman once told me. For most of life, it’s easy to imagine always staying one step ahead, easier to accelerate than to stop. This house is where Jean Claude stopped traveling fifteen years ago, long enough for his weary soul to finally find him.

Aloneness is a state unto itself. Strange things happen when there’s not another soul for miles, when cities are a memory and the closest thing to a motor is the sound of boars plunging their snouts into furrows. A change came over my father in this remote life, one long sought and finally embraced. “I unfurl endlessly,” he says, as his arms encompass the land. Living without interruptions, the soliloquy of self, that’s when memories can surface. The past slips in; its murmur grows clearer. Stray recollections start to make their way home: Come right in, the doorway is no longer crowded by new experience.

Something there kindled his memory of the war, and I went back to listen.

It takes seven hours by direct flight from New York City to Paris. Once at Charles De Gaulle Airport, the next step in the low-cost trip southward is the train station Marne la Vallée Chessy, nineteen miles east from Paris, following the tourists heading for Disneyland. From there, the high-speed train takes slightly less than three hours and a half to Aix-en-Provence TGV station. Even when you disembark onto the sterile platform, you know you’re in the south—the warmth, the landscape, and the sounds. The train continues to Marseille, but the city of Aix is still twenty minutes away by bus. That’s where he’s waiting.

We spend the night at a friend’s apartment. I tell him why I’m here. The war, why not?

There’s that time with the swastika smeared on the house, he begins.

No, I say, don’t tell me yet; wait till we reach the hillside.

We take the morning bus to the valley, another three hours to Malemoisson, a stop on the edge of N85, where we’re the only ones to get off the bus before it makes its way to Digne, the département capital, famous for being the starting point of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. His jeep is in the parking lot nearby. Then we start the trip into the valley, the seven miles of winding road through fields and small towns, like traveling at the bottom of riverbanks with hills on both sides, heading upstream. A sharp turn left starts the climb before you reach the postcard town of Thoard. The road narrows; houses become scarce. After a couple miles, another turn left towards the hamlet of Les Bouguignons, past two houses and a chicken farm and onto a dirt road. Now it’s stone, dust, and looming cypress, oak, pine, and mulberry trees for twenty minutes, steadily climbing a path that feels like one long bump. For years there have been car pieces strewn on the way, from those who braved the climb and from when the sailor drank himself into the countryside. My father has added a couple of oil pans, bits and debris of his own, paid in tribute to the climb, but the road he curses is his moat: It ensures no one will try to see where the path ends.

Then there is the house, above the lavender fields, the thick walls of stone. The key is hidden in a corner by the door, and once inside there awaits the large wooden table on the first floor, underneath those age-old beams he says make him think of a ship’s hold. It’s the best place in the world I know for conversation.

Once the wine is poured, he starts by telling me about the fire. The flames, the last bucket in vain and the firemen. By the time they arrived the base of the electric pole was burning—he concedes that would have been a bother—but the gas tank was still far off. Then again, salvation in the nick of time is what his life is made of. Though no one believes him when he says so, that’s how it goes.

And to prove it, look no further than that morning in 1944. Then as now, disaster averted, and a wormhole in the conversation takes us back seventy-three years, to the moment that marked his childhood: “It’s the same thing”—all seems lost and then, after the flames are spent, what remains is only a funny, self-deprecating anecdote over aperitif, something else to write about.

Except he never wrote about what happened during the war, not in full, not directly. In some thirty books of fiction and non-fiction there are tangents and fragments, but a man who made a living telling stories withheld this one for a lifetime. Until now he’d shared bits and pieces with me, memory flashes of littered ammunition, wartime deprivation, German soldiers, and ambiguity.

I first tried to write what little I knew six years ago and failed. “Your story is bullshit,” he told me. “You don’t get it.” But you can only tell what you’re told. Now the flames opened a clearing into the full story. So, we started talking last summer, a recorder between us, alongside the wine.

For a month he went back for me, to the period between 1940 and 1945, to the time that left scorched earth inside him that his memory traces like a finger upon a scar.

“Life is a series of ruptures and betrayals in which you end up alone. Since then I’ve always been expelled from everywhere; it’s a vocation. There’s no place where I’ve remained, and in the end, I find myself here,” you tell me, and at the road’s end, I’d like to know why.

It isn’t really the war I’m after but the start of the flight. You were born in 1933 and lived many lives and left each one without seemingly looking back. Peace has come after you’ve severed all the ties. Never had a cellphone, never used a computer or the Internet; no TV, no one around, and goodbye to all that. Whatever keeps on happening out there in the world barely survives the climb. It took a lifetime to get this far, far enough. What propelled you here started when you were a child and your childhood was war.

Because I’ve come to learn that by the war’s end, the die is cast: there will not be a straightforward life (if such a thing exists), instead the active rejection of one. There will be no belonging again, no being betrayed again. Fool me once…maybe once was enough.

When I was seven, my mother and I left for México, her country, and that past that crept at the edges, that blank instead of a family history on your side, became all the more foreign, an ocean apart. That started changing during a holiday in college. I found old black and white photographs in the trash, you put a finger on a soldier I’d taken out: that’s your great-granddad. That’s where I started to listen, trying to put the fragments together and failing. I hadn’t learned how to ask.

When I finally did, something had changed; maybe it was all flooding back. You’d stored it away without ever fully closing the lid, memories still restless, half-buried, bubbling up. It happened at the beginning of your life, before you learned to dodge it all, a time when you were still unarmed. You can let go of people, but not of that.

- We talk about it because it interests you, but nobody gives a damn. This is seventy years ago, right? It’s been pushed down for some time.

- But it’s still stuck inside you, Dad.

- Because I’ve survived, while many in my generation are already dead.

- I remember you told me about it growing up.

- It’s something that…when you’re little, marks you for eternity. It’s something I’ll die with, I was nearly born with and I’ll die with it. That’s all.

We sit across from each other, you on a cushioned chair and me on a bench against the wall, near the sliding glass door where nightfall has subdued the distant woods, the large oak tree, and the trail left by the fire.

War? It was about time.

PART I: THE FALL

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” —L.P Hartley

Once upon a loss or another, are all the various beginnings for this story. Start with a speech on the radio announcing defeat; start years earlier with a death in Africa, trace it back to a lost manuscript or long, long before, to the plague that wiped out the vineyards. Start with an absence, a loss not yet fully sealed, sparked by those words passed on to me not to inherit anything:

“Some families explode in midair,”

you tell me of our kin. Down the ladder of generations, I wait to pick up the pieces.

To understand what happened, to them, to you, I pull the furthest thread. Start with a name and a place: the Godard family from the département of Haute-Saône, in the region of Franche-Compté in northeastern France. Sometime on this earth they toiled and bred, in distant lives reduced to summaries that echo those of countless other migrants: poor Catholic farmers of the nineteenth century. The vineyards were their bread and butter. Yet, over the course of a lifetime, chance and necessity will thrust this family of laborers into the world, from their lands into war and to Africa.

The family doesn’t actually explode in one go; it falls apart over time, a series of implosions into silence and voluntary amnesia. It begins with the plague.

Among the myriad reasons for who they became, the smallest is the most convincing: Phylloxera, Daktulosphaira vitifoliae, “almost microscopic, pale yellow sap-sucking,” an insect brought from North America that ravages the vineyards of France in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. With it, Stéphane Godard left life on the wasted lands for a career in the military health services. World War I takes him to Salonica, or Thessaloniki, on the Macedonian Front. He never spoke about it. He’s my great-grandfather, your grandfather. Henceforth, the family’s turning point.

“They were Franc-comptois, farmers originally, working the vines, then came the phylloxera, the vines died, and they were forced to join the army. It was a huge empire and so there were limitless possibilities,” you explain to me.

To join the army was to see the world in a way the life of a farmer would never allow—a way to change one’s fate, and perhaps to move upwards on the social ladder. The start of a flight, Outre-mer, as they called it: overseas.

In his book Small Lives, writer Pierre Michon gives insight into a poor French laborer gambling everything on a life in the colonies: “His vocation was that uncertain country where the childhood pacts made with oneself could still, in that time, hope to accomplish dazzling revenges, providing you submitted to the haughty and summary god of ‘all or nothing.’” But that story, great grandfather Stéphane’s, was never told. It could have started there, too, with a memoir written decades before I was born. You titled it Le Phyloxéra, in French. It was to be Claude Courchay’s first book, on the twist of fate that made his grandfather Stéphane Godard. Of that first attempt to salvage the pieces, there remains only a mention on a half-ripped page.

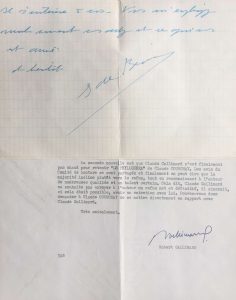

The envelope reads: “To Mr. Courchay, 4 Cours A. Briand, 84” in the city of Orange, in southern France. The letter is from Simone de Beauvoir, your sometime literary mentor. It’s undated, probably from the mid-sixties, her handwriting mostly unintelligible. The author of The Second Sex begins by asking “Do you want us to have dinner on Monday 25?” Her folded, handwritten page is the companion piece to a typed one, of which the upper part has been ripped. It is addressed to Beauvoir, from her editors at Gallimard:

“The second news is that Claude Gallimard is finally not hot to retain ‘THE PHYLLOXERA’ by Claude Courchay. The opinions of the readers committee are divided and finally we can say the majority rather favored refusal, while recognizing the author’s numerous qualities and certain talent.”

Very Kindly,

Robert Gallimard

(Signature)

The letters from Beauvoir and Gallimard

I don’t know how you took the rejection. You certainly remember it more than you do the work itself. To this day you still grumble about the writer Raymond Queneau, long dead, who allegedly disliked your book. Afterwards you succeeded in losing the manuscript, and with it your grandfather’s tale. Hence this story, its genesis, waited another five decades to be retold. What was lost was that the gamble of the army paid off for him, if gamble there ever was, if ruined vineyards weren’t reason enough to try anything else.

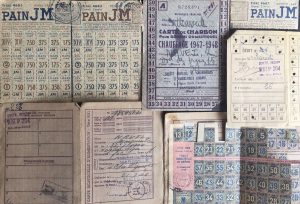

Stéphane features prominently in the ramshackle family museum I’ve inherited, in what you produced when I started asking. It’s a brief archeology of departed loved ones, selected pieces they would have chosen, or not, of which time becomes the final editor: food stamps, military passbooks and records, postcards, children books and awards. And photos. Here’s the oldest of them all: Stéphane stands upright in military uniform with a round collar and two lines of buttons, complete with a kepi on his head, his right hand on his hip, his left on his sword, his upper lip covered by the thin moustache of the time. He looks straight at the camera. To his right, his wife, Rosalie, is seen in a hat and a strict, long, dark dress, her expression puzzled, her gaze lost somewhere outside the frame. They’re in a garden. The exact date is unknown, the name Moghar is scribbled in faded pencil at the back of the photo. They’re in Algeria around 1900 where France has just built a railroad from Ain Sefra, the southwestern mountain town, for twenty-five miles to the Moghar Oasis, on the edge of the Sahara Desert.

Rosalie and Stéphane

A lifetime passes until the next photos. Remarkably, the most recent of the two, from 1931, shows a near-repetition of the Moghar shot, with both grandparents standing in the garden side-by-side, though inverted, with him to her right. Things have changed with passage of time: Rosalie and Stéphane are older and stouter, his moustache larger, both transformed in their expressions. Decades on, they’re smiling; both bareheaded now. In between both images is a proud family portrait with their three children, Marcel, Margot, and Marie-Louise. Of your grandfather you remember a well-rounded life: “He was satisfied with himself, had his Rosalie alongside him. He was very jovial, had a paunch. Grandpa Stéphane with his nice, big moustaches, gentle, with a satisfied air: the assurance of the warrant officer. He was something of a character, the summit of the noncommissioned officers. Never really fought, never really worked, ate well. A guy happy with his lot, he had had a good life. Instead of misery as a farmer, he was an officer.”

After his career in the colonial army, old age found him as a concierge at Michel-Lévy Military Hospital, at 84 Rue de Lodi, in Marseille. An antique photo shows a massive square building, with a fenced gate and large walls on which its name was adorned with crosses. The main entrance was large, with a half-round transom, beyond which Stéphane must have stood at the “entrance desk” where your grandmother accompanied him and sold chocolate to the troops and visitors. It’s at Michel-Lévy that shots and vaccines were administered, for typhoid, diphtheria and more, to the soldiers heading abroad.

Young Margot and Marie-Louise grow up next to this entrance desk, girls of the seafaring city, its port and breezes. From that vantage point, they see a daily procession of men bound for the furthest reaches. And while Marcel, the son, became an electrical engineer, it was the two daughters’ marriages that further certified the Godard’s station in life. A strict religious education by nuns prepares them for the restricted role then expected of women. Amid the coming and goings of uniforms, the Godard sisters find two to their liking. Their betrothed are both northerners and in the military health services, just like daddy, and now it runs in the family. All is at is should be.

The Godard children. Margot-Marcel-Marie Louise

Fair-haired Marie-Louise, your mother, marries the Normand, Maurice Courchay, who becomes your father, who had a history not unlike his in-law’s, of humble background, with a mother who had been a textile worker in a backwards region. “It was very feudal still in Normandy, the lords in their castles and the little people. My grandmother was the little people.” Both Maurice and his brother had gotten away through the army, the first as a male nurse and the second a captain in Indochina. The eldest sister, beautiful Margot, marries “the giant” René Navel of Lorraine. Born in the city of Sedan in 1900, he became a military doctor.

For these men, life existed in defined trajectories. For Stéphane, for Maurice, serving was the way to be upwardly mobile, and to get food on the plate. “In the army you eat, quite simply. The army fed you, gave you a rank, the army gave you responsibility, the army made someone of you. If you wanted to study you had to go to the seminary, where you’d learn Greek and Latin, and when you got out you joined the army and left for the colonies.

The church gave you schooling, and the army gave you a job and fed you.

It was a system. It was extremely important. It was that or being proletarian.”

This family’s way will be the army, the prism through which to peer into their view of the country’s fate, their allegiances and, in time, their downfall.

Within a generation they become something new. From Stéphane onwards, the family finds a definite identity, a “type,” that no longer exists today but that once spoke as clearly of a way of life as a priest’s or a teacher’s. It meant they had photos in uniform in foreign landscapes, men at war at one time or another, implied roles and beliefs and a place in society. “It became a military dynasty, and a colonial one because there was the empire.”

From then on, the marriage of Marie-Louise and Maurice seems preordained; work abroad for him in a military hospital and she to follow. For their children to be, the lot of “a family of military, you were born in Dakar or Algeria, somewhere in the empire.” And so it goes, at first. Maurice Courchay is sent to serve in Dakar, Senegal, in Western Africa. Their children come in quick succession. First a boy is born, named after his father. A couple years later, in 1933, along comes Claude Courchay. A daughter soon follows. All three children are christened after the Virgin: Maurice Marie, Jean Claude Marie and Marie-Line.

Nothing remains of that period, not a photo, not an address or memento. Mother is at home and father works. “Being in the health services you thought you were going to tend to the population.” Or the other way around: a Senegalese woman breastfeeds Claude, who rejects his mother’s milk. Whatever the realities you never knew, there wasn’t time. Before you can begin to retain this life, it comes to an end in 1938. Here again, another possible start, another implosion, another loss: death in Dakar.

Military nurse, Maurice Courchay, leaves behind three small children and his wife, Marie-Louise. Swept away by malaria. Both Maurice senior and Claude got the fevers, the yellow skin. Only the son lived.

“My mother wrote about me from Dakar, ‘my poor Pimpin is going to die.’ I had malaria and dysentery. I was mostly dead; I don’t know why I survived. I guess I must have since I’m here. My father had it also. I don’t know him, but I love him, and I missed him enormously.”

The father’s death precipitates the family’s return to France. Marie-Louise is suddenly a young widow in a country she didn’t choose, jobless and left to care for a family that had barely started. “A young woman, completely innocent, ends up in Dakar, pregnant…three kids.” So much for that preordained life.

Claude is five when they leave Senegal. After that, what’s left of a birthplace sealed away by loss? What does a child remember? The kaleidoscope of early memory, stray images coming into focus: a wax cloth with insects buzzing on it, the warmth and the sound of a herd of goats passing by every evening. The stuttering reconstruction of distant experience: “I remember Dakar. There was a house; there were stairs. I fall down the stairs and open my chin. An ant stings me inside my shoe, a stink ant”, which in French bears the gruesome name of cadaver ant.

Amid all that, the crown jewel salvaged from forgetting: a single memory of a father. “Mother scolds me, father is very sweet; a giant, very tall for the 1930’s. My mother had forbidden me dessert. I see my father, like a good force…” After his mother has grounded him, Claude sulks to the kitchen and there his father sneaks him some cake. That single paternal gesture, that’s the last sight of Maurice Courchay; there’s little more besides. I first knew of his name from reading my Mexican birth certificate, which lists each parent’s parents. The only remaining photos are a couple miniatures taken in Marseille: tall and sturdy, a strong jaw, wavy light hair. In one photo he’s standing alongside others, with a wry smile; on another he sits with Marie-Louise on the grass with his legs outstretched. He’d been born; he’d risen above his station, married into the profession and multiplied. Then the fevers, a corollary of stray facts, and a single memory that lives on.

There’s nearly more to be said of the ship on which the family returned to France, leaving Dakar and with it a grave none of them will ever see again. The ship was built in 1925, in a naval shipyard by the Mediterranean, with two steam engines to power its way to Morocco, the Levant and beyond; these destinations written on the old promotional poster by the Paquet navigation company, showing the ship’s stylized rendition reflected on the swell: Marshal Lyautey, written on the side of its hull. As luck would have it, I came across a print of it decorating a French restaurant, in the airport, in Mexico City. Whether or not the family saw the actual poster, their origin and final port was marked there, the route from Senegal to Marseille, which they took in 1938.

The Marshal Lyautey

“I was on the boat, I remember some sort of bird, that screamed when you made it swirl; a toy. We were on the boat’s bridge, the Marshal Lyautey. It was good.”

They sail on a vessel whose name foreshadows the destination. In Marseille there awaits another father, for his widowed daughter, Stéphane Godard whose hour of glory in WWI also bore the name of Lyautey at the bottom:

The Ministry of War

By the decree of 1914

Judges:

Single article. – Are inscribed on the on the Special Board of the MILITARY MEDAL, from December 25th 1916, the military whose name follow:

GODARD, Stéphane, Jean, Baptiste, active sergeant of the 15th Section of military nurses.

“Served in campaign with zeal and devotion and renders precious services in the accomplishment of the special services of which he has the charge.”

Paris, December 29th 1916.

Signed: LYAUTEY.

The award, on brittle paper more than a century old, was in the bundle kept on the hill, passed on by hands unknown to the last heir, and from you to me.

Now your story starts in earnest. The stage is set for the memories to be grounded, encompassed by the theme of the father’s absence that will preside over your childhood. Loss draws the family circle tightly under the same roof.

Having nowhere else to go, your mother turns to her parents, Stéphane and Rosalie. It’s a far cry from a festive family reunion. “When they retired in ’38, we arrived orphaned.” It’s not just your preordained lives that death has rewritten. Whatever plans they had for their old days have been derailed, and the villa your grandfather bought after a lifetime of service is about to get crowded. “He had to take in his daughter with three kids and tighten his belt. Unfortunately, his daughter was a widow and we were ‘Pupil of the Nation.’” And here’s where I first learn that term, Pupil of the Nation. For now, it stands solely as a euphemism for military orphan.

So there are six people in a home meant for two. With a couple of retired seniors on a pension, and only her own pension as a military widow to provide for three children, Marie-Louise, with only the nun’s pious upbringing and no career training, needs any job she can get. “She ended up in Marseille without a penny, so she worked at the dates. If you were just arrived, you went to the dates.” That’s the date fruit plant, where the loads brought from Algeria were prepared for selling. “Marseille received bunches of jumbled date fruit, they had to be readied: clean off the sand, take out the stem, make them presentable and edible. It was sugary and sticky, something that ends up disgusting you. Poor women worked there. When you’re not qualified, that’s the job you can get.”

Other jobs followed. First came a step up, selling at the Chocolat du Prado, with a factory next door that spread the smell of chocolate onto the sidewalk. Neither job left a good taste in her mouth: “For the rest of her life she didn’t feel like eating dates or chocolate ever again.”

Whether by choice or convention, she never married again. “After her widowhood, she was proposed to, but she wasn’t about to repeat the experience.” Hers was a world where “decent women had hats on, didn’t let their hair loose. Those who did were deemed prostitutes.” The word that recurs most in speaking of your mother is “sacrifice.”

Still, it could have been worse, were it not for the generosity of that old couple. “My mother adored her mother. They had taken her in. Without them I don’t know where we would have ended up.” You too share that gratefulness. Though it’s the first time I remember you saying it, I know. Stéphane is my second name. Crammed somewhere between a Mexican first name and a Normand last one, with the added Marie at the end that seemingly no one in the family can ever be spared. Until college I saw Stéphane as just an initial, something to be discarded when the teacher asked what you preferred to be called on the first day of class. You never told me, but you asked my mother to give me that name. He’d been you grandfather, you told her. He put a roof over your head.

Unlike your mother, for you Marseille isn’t a sorrowful homecoming. Marseille gives you the south. In a drifting life, the region is your one place of return, carried with you always in the inflections of an accent claiming belonging.

The city you arrive in is a commercial port, the most important in the country. You and your family were among the 819,000 passengers that graced its quays in 1938, atop 13,000 ships that came and went.

The place you remember still seems provincial, stuck in time and space, “a hollow” between hills stretching along the coastline. It was “a pretty, quiet city, there were plane trees everywhere, all along Rome Street.”

Despite the duress to come, or because of it, it will be your hometown, even if it’s to despair over the changes that erase what you knew: the hard-earned right to lament your lost city.

Nowhere as in the south does the distance narrow with your past. Over the years, when you and I visit its cities together, you point to details that have been there for as long as you can remember, still there to be shared in their quasi-sameness: a building or passageway cleansed by the city but otherwise unaltered. Some years back, during a rare outing to Marseille, you looked out the backseat window and started telling of a hospital on the street we had just taken, a place where your grandfather had been a concierge, where your mother had been born, where she had met your father, where she later returned widowed to work as a switchboard operator. The hospital was demolished in 1988, the year I was born.

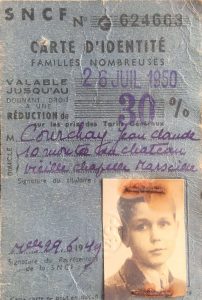

It all comes across as overwhelmingly quaint in your memories, a child’s geography settled by places that could be listed with an accordion playing in the background. From your grandparent’s neighborhood, La Vielle Chappelle (the Old Chapel), to your church in nearby Bonneveine (Good Fortune), where you attended Mass at Notre Dame des Neiges (Our Lady of the Snow) “where there was allegedly a miracle and it snowed on a 15th of August,” or going hand in hand with your grandfather to the school of the Lapin Blanc (White Rabbit). All those “nice kitsch names”: the words to spell the age of innocence.

It’s an enclosed world on the outskirts of Marseille, the old world past generations recall in lost details where you could still find “cheese and snail salesmen, each singing their merchandise as they went,” along narrow streets of your sun-kissed South. “It’s a life straight out of a book.”

Though not all changes are bad: “people didn’t have septic tanks, people did their necessities in buckets and chamber pots, and the torpilleur passed by, pulled by a horse, and the employee poured the buckets in the barrel” — So much for the good old days.

In narrowing concentric circles, we draw nearer, from the city, to the neighborhood, rising steeply along villas, secluded and preserved before the storm to come. You scribble me a map of the land of childhood. Up from the sea of curves on my notebook, past the arrow of three streets, turn at the grocery to where with two drawn parallels you ask me to imagine a rise of gravel and large steps, which Pimpin, Kakou, and Bibi, you and your siblings, run up and down, screaming and skidding, often falling—children in short trousers and dresses with knees stained purple by the mercurochrome disinfectant you used on me too. Up and down the cul-de-sac of Montée du Château, the Castle Rise to the building whose gates closed the street into an impasse and gave it its name, atop Collet hill, overlooking the Mediterranean.

Collet Castle

“The castle enclosed the Montée du Château, there was a cement wall, with two pillars, which blocked the street completely. It occupied all the top of the hill; there was a huge black gate, behind it a park, with paths lined with box trees, and this completely tacky castle with round turrets, a phony nineteenth century castle. This guy had money and had made himself a nouveau riche castle.”

In a few years it will be gone, its turrets and balconies destroyed, yet another of those sites where people wonder about the strange old names one finds in the city. The sign today still reads Montée du Château, and sure enough you’ll see a street that rises, yet at the end of it there are just residences. No castle in sight.

On the slope you draw for me, about halfway to the right, a scribble signals the home of Marcel Godard, the eldest child and the electrical engineer. Then past the villas marked “unknown,” there’s a gate. Welcome home.

It’s a narrow entrance, with a small garden, then up a flight of stairs to a small terrace surrounded by plants, where children play and adults enjoy the garden. The front door leads into the kitchen with the coal stove on which Stéphane likes to grill cheese. Then the dining room, always liveliest on Sunday when the men play cards, filled with “magnificent furniture from the grandparents, old and splendid, maybe centuries old” left from that other life in Haute-Saône. The most memorable relics were a dresser and a pendulum clock that “rang every half an hour, and every hour, making an abominable noise.”

From there a hallway leads to the room your brother and sister share, then to the left, your grandparents,’ and in front, a room for Marie-Louise and you. “I had to share the bed with my mother.” Every night she tells you: “Turn to the wall, don’t move” as she changes into her long nightgown. “She should have slept with my sister.”

There isn’t a single photo of your father in the house, you remember.

There aren’t any bathrooms either. “We washed in the kitchen because it was warmer; in tubs of zinc you got water poured on you. Like in the paintings by Bonnard. That was normal, no showers, no bathtub or bathroom, that’s the way it was. We washed on Sundays, once a week to be clean for Mass.”

Running water requires effort. “You had to pump water. Obviously, grandpa had fought in Salonica and all, but he wasn’t up for this anymore, so we pumped the water and it reached the kitchen and a water filter in the house: not so much running as pumping water. We pumped for hours.”

Wooden stairs lead to an attic filled with a lifetime of trunks, and at the end is a wooden balcony, from which “we saw Borelli park, we saw the sea, we had a vast view. We saw Marseille.” These were your favorite parts of the house.

Downstairs was your other refuge. Two large steps take you out to the back garden, surrounded by walls of stone, where the yellow cat hunts lizards and scorpions can be found nestling under the rocks. In the left corner were Stéphane’s rabbit cages. “My grandfather had some rabbits, he fed them. Once in a while, he’d kill one, take out one of the eyes to bleed it, save the blood because everything was used. We ate rabbit. He skinned them, dried the hides on a plank and tanned the skins and made fur collars.” His retirement pastime was a return to his roots. “He was a farmer, after all.”

At the center of that garden is one of childhood’s symbols, “the magnificent fig tree,” towards which memory gravitates, under which books are read and where one day the German officer will make his entrance. “There were figs, I ate them, they were delicious, there were two seasons,” the breba figs of spring and the purple summer figs you love. All around were the other villas on the hill. “It was good because it was a place where we were away from it all.”

The two activities outside of the home, school and church, inscribed themselves within this closed circuit. “I never went to the port. My path ran from Montée du Château to Notre Dame des Neiges and the Lapin Blanc. That was my universe.” And it was a religious one.

“Notre Dame Des Neiges was a normal church. What was interesting was that next door was the parsonage where the priest showed us movies. He had a small projector. Priests back then tried to have an influence on youth, you needed to make the first communion and the confirmation. And catechism. ‘Only one God you will adore…’ the Decalogue.” You still know it by heart: “What is God? God is a pure spirit, infinitely good, infinitely perfect…”

Stéphane didn’t accompany your mother and siblings to church, as a man of French republican values, he was not religious, and in time of fasting he made sure to have another serving of herring.

Still, he walked toward the church every day, but only because he took you to school in the mornings. “My grandfather took me by the hand, sometimes I’d trip and he’d nearly fall: I was little and I had a large forehead. I liked school.”

The teacher was M. Chamonard, who liked to have an orderly class. “Each had his bench, with his inkpot, you came in and lined up next to your bench. You waited until you were told to sit, and rose every time an adult came in. You stood silent and crossed your arms. There was lots of discipline and politeness. There were moral courses…we used slates, chalk, and had a rag to clean it.” You remember him punishing you once for erasing a single letter in a word on the blackboard, making a vulgar wordplay.

Sensory memory is acute here. “I remember smells, white glue that smelled like bitter almonds and tempted us to eat it, the smell of ink…penholders were made of bone, with images on them. I learned calligraphy.” And the grand history of your nation in “naïf history books.” All through your school years, you were meant to stand out and win scholarships. It was your role, that of the worthy fatherless boy, implying you were deserving of any help available to continue to study. “I was the best in the class. That’s what was expected of me.”

It was a system that thrived on perpetuation. Education was the introduction into something that existed long before you, an unmovable world inherited from the century before. “It was curious because every generation learned the same recitation. We went up to the blackboard and recited. Grandfather had learned them, father had learned them; there was a communion over time, a common culture, through the same recitations; the same benches, the same inkpots. The same smell of chalk.”

And you nearly learned something else, too. “There was a little girl that wanted to kiss me, but I didn’t want to.” Nearly a first kiss, nearly eighty years ago.

From this narrow circle, knowledge of the outside broadened slowly, like ripples in water. In this isolated neighborhood, the radio brought home the wider world, though what reaches you does little to dispel the parochial imagery. “We sat before the radio and listened. The programs were good-humored. There was a show called ‘My Village,’ all very nice and sweet, like you’d speak to children, it was something pretty paternalistic. We listened to the radio ‘It’s noon, sit down, sit down to eat, it’s noon, the little mouse is saying,’ it was dumb, and the radio had an enormous importance. There was only radio.”

The other teachings of the day and age, the lessons and values that stuck with you came from the uncles and aunts. Among those teachings: You were the poor cousins.

“Marcel was the one near us, at number 6 Montée du Château. Marcel had a higher standard of living than us because he was an engineer and he had a small car, a Rosengart.” It was a sign of certain social standing. “Cars were rare back then.”

He was the eldest and had done well for himself. “Marcel was tanned, always smiling, quite ironic, kind but superior. He had class and style, a sort of casualness. He was an engineer, after all.” He’d been “impressed” by how your father, a Normand, ate cheese. His soft spots were his wife and his cat. “He was in his armchair, he listened to the radio. He had a beautiful cat, with long hair, whom he caressed.” He had a passion for his wife, Aunt Yvonne, over whom there might have been some fuss because she’d had a son with Antomarchi, the Corsican. “The son was handsome. Marcel married her anyway.” Yvonne, you remember as a bit aloof and “very thin.” She soon became known in the family for a strange trait. You always knew where to find Aunt Yvonne in bad weather. “She was permanently surprised. A bit lost. Except during storms, when she’d lock herself into a closet. Panic at the sight of a storm. The thunder!”

Then there were Margot and René. Back in the days of their youth at Michel-Levy hospital, the Godard sisters had both made similar choices in their spouses, yet from then on, their lives had diverged.

While your father worked then died in Dakar, Margot’s husband, René, had built a profitable business. “When René finished his time in the army there were no fridges yet. Before American electric fridges there was the glacières. He got an associate and made iceboxes.” They were made of zinc, with cork inside to preserve the cold. Back then ice was still delivered to the houses, “trucks passed by with huge blocks of ice, you would go down and they’d break off a piece of ice for you, which you’d put in your icebox to keep it cold.”

So Margot and René had a very different life from your own, of which you caught glimpses when you visited them. “Sometimes we went to her house and it was much better, another neighborhood, a large house, with a rising staircase with his collection of helmets and sabers displayed there. René had put that up. There was a large terrace, and still another floor with terraces.”

To you, they were the image of the happy couple. “He was a giant, extremely kind, always wanted to please, he helped us, brought us food.” She was your favorite relative, “I liked Aunt Margot best, but I seldom saw her.”

The contrast between the families was not lost on the children. You spent time with your brother, Maurice: “I had no father, so my brother took the role up a bit. He did everything well. He was responsible and good. I tried to keep a low profile.” When you were by yourselves, you could say those silent things that welled up inside. “One time my brother and I were talking, we were sitting out back, and we dreamt, a bit like in fairy tales, that we weren’t really of this family, but orphans, that maybe this wasn’t really our family and there was a better one. I was much better at Aunt Margot’s. I could breathe there.”

Meanwhile you mother “left for work in the morning and came back in the evening,” toiled by day and shared a bed with you at night. And whereas your mother had worn the black of widowhood, “Margot had her man. She was extremely sweet.”

Margot and René

And here the image of Margot and René together was a further reminder of the absence at home, and not just the physical absence but the erasure of Maurice Courchay. “The photo was exposed nowhere. My mother must have resented him. She had been young, innocent, instead of having a normal life, with a normal husband, she found herself in Africa and a widow. She was young and finds herself nearly penniless, with a very small pension and forced to feed three kids. You’re a young woman, still dreaming of love, and you find yourself sacrificing yourself. It mustn’t have been very fun. She must have remained horrified by sex. She was young, there were guys, but she turned down, everyone. She did not want another man.”

To you she never spoke of him, only to your sister, who will one day let you in on what was said in those heart-to-hearts that never included you. But that’s far away, in adulthood. For the time being there’s no traces of father, not even in the mirror. He’s in your face less than in your brother’s and sister’s, who are clear-eyed, blonde Normand types. You take after your mother, the Godard. The search for him has the opaqueness of a blank slate, from which no image arises, no gestures to imitate, no tones or subtle mimicries, no starting point from which to later depart into individuality. You always had to look elsewhere. There was your grandfather and uncles.

It was on Sundays that they all came together for the weekly family lunch. “We ate vol-au-vent, there was good food before the war”—puff pastry filled with fish or meat, with a sauce on top. The aunts and uncles would come over to the grandparent’s house, food was served, and afterwards the men had the table for the things men did, “and meanwhile the two women…” There were roles and gender was a hierarchy.

No drinking for the uncles but a “room thick with smoke” while they played cards… “René came on Sundays, he played cards with Marcel. There were the chips, the cards, and it lasted for hours, for all afternoon. The two men played against each other and René absolutely wanted to win and did. They smoked enormously, and we choked. There was a cloud and smoke and ‘Your turn Marcel!’ It brought him back to life. It must have reminded him of his career in the army, where they probably spent hours playing.” For René it was a moment to relish. “It was very important to him, I think it was the great moment of his week. Belote and smoking.” Belote, an old soldier’s card game. For René, one card game brought to mind others, and an entire, distant life.

Cards were a man’s thing and you weren’t one. “They were good to me, except at the table you could only speak if allowed to. You had no business talking. You waited, asked permission to leave the table. You’re a kid, you don’t have a say in things.”

And as you watched through the smoke, you caught a glimpse of that absent presence in the room and the question left in the void: who was Maurice Courchay? As René shouted and reenacted his empty hours of military service, you gleaned something that told you more about your father than the few stray details you were afforded: that the way life once espoused by the men of your family, the career that took them from nowhere and transported them to faraway places—to a great colonial bazaar that infused them with pride to go along with all their stories—had been the great adventure of their lives, just as it had been of your father’s life, too. A life into which maybe, one day, you’d be allowed to partake. “You became a man after the military service. That was the rite of passage into the virile age.”

René was the door into that world, by his presence, through what he said and the gifts he gave you. He was the early male influence, complementing your grandfather’s, introducing you into the world of men, the army, and war.

When René came on Sundays, he brought the newspapers, where you looked at the photos and illustrations and read some about the Spanish Civil War; maybe the men discussed it in front of you. They had very definite opinions. Some lessons filtered through: You should “trust not so much in state as in the army, because the state is rotten, but the army has a chief.”

Wealthy Uncle René brought you toys, and they were the right sort: “I’d play with my little lead soldier, my Solido cannons in front of the castle’s huge gate. I had a small Solido cannon… I had a small Solido mortar, which had a spring and launched a small shell: my own little 77.”

And didn’t René indulge in similar games in adulthood? He’d been born in 1900, lived his teens in the onslaught of World War I, and soon after joined the ranks of a victorious army and spent his best years serving it. He’d done well afterwards, but then we all cling to mementos of the time that gave us meaning. “He was bored and collected enemy trinkets, then took to sculpting artillery shells. You had to kill time somehow.” You had your toy war; he had his collection of wartime paraphernalia, the “enemy trophies” you inherited, and with which you one day decorated my childhood room: Prussian helmets from 1870, French and German ones from 1914, grenades, guns, swords, knives, insignia. Boys will be boys. Boys will be men. Men will be soldiers.

Furthermore, they’d been in the colonial army, a pillar of the empire. Greater France. Another layer in the natural order of things: “I was young, there were exercise book covers and at the back of them was the empire, painted in red. People thought it would last forever.” The lesson was “the civilizing mission of the colony.”

“I collected stamps, magnificent stamps from all over the empire, as my mother received letters from Dakar and elsewhere.” Packages came from far away. “They sent us coffee from Dakar. To receive coffee was like solid gold.”

It all comes together, the smell of coffee, Stéphane’s career, René’s nostalgia, along with windows into distant places where France extended its rule and where your grandfather, your uncles, your father had all gone to serve the “mission.” Civilization, you’re told. “That’s what they told us: generous France was going to emancipate ‘primitive’ populations. It was all for their good. Everything was good and pure. Magnificent.”

The child aspires to do “good” as he’s been taught. “I didn’t want to join the army, I wanted to be a missionary, go abroad, my robes, my cross and a large beard. I wanted out. My father had died for France and I wanted to have an honorable death, to earn a beautiful death.”

Now suddenly the past breaks, with your laughter.

Beautiful death, you say and laugh out loud to dispel the weight of illusions once held dear. The narration stops but I leave the recorder on. It’s on the table, alongside the bottle of home-brewed liquor from which I pour us two more glasses. We drink, and then I ask.

- Why is it that your father “died for France”?

- He had died for France because he was a French soldier, in the French army, serving abroad in the interest of France, and so he died in service of France. And so, I was, we were, “pupils of the nation.” Which showed how much the nation had its eye on us, so to speak, how dear we were to the nation.

Amidst all these aged beliefs, the shadow is ever present. The brief life of Maurice Courchay, buried far from his homeland, disappeared behind his role, his station in life. It’s the last bond you shared: He’d died for France and you were left fatherless, but more so, a Pupil of the Nation.

It was a status instituted in France by law in 1917, through which children “orphaned by war” in the carnage of World War I were “adopted” by the nation, as way to safeguard all those many broken families.

The law provided aid for your mother’s three children, in addition to her pension. Maybe a scholarship, you don’t remember the specifics. It would have been something the teachers were aware of, a badge of honor instead of a father. In his posthumous book The First Man, Albert Camus writes of a boy that could well be you: “During the examination at the beginning of the year he had been able to respond with certainty that his father was dead at war, which, in short, was a social standing, and that he was a pupil of the nation.” This is what you are, what you ought to live up to. A title. You’re something more than a boy deprived by an absence.

It’s the missing piece that crystalizes all the other the beliefs, the foundational sacrifice upon which your world is created. You were the son of a man who died an honorable death for his country and its great mission in the world. The nation is indebted to his sacrifice, for his untimely passing. The son, dare I say, of a hero.

You laugh at an old ghost that’s been tamed to provoke not sorrow but mockery: beautiful death, pupil of the nation. Can you believe it? Yes, you did. And you would hold on to that belief, even after the war, after the rest had long crumbled. It’s another unquestionable truth, amidst a whirlwind childhood in which you weren’t meant to ask questions.

“Things happen, one day you’re in Dakar being bitten by ants, then it’s warm, in the evening you hear goats go by. A herd of goats passes every evening. Then one day you’re on a boat, then another. You’re in Marseille, and it’s good because there’s a fig tree, or perhaps it isn’t because you have to share a bed with your mother, and then you go to the school of the White Rabbit, and that’s good, and you have to go to Mass, you have to go to church a lot, and on Sunday there’s the card game and that’s it. That’s it, that’s good. If it were otherwise it would be exactly the same. Things exist; it’s not your place to argue. It is as it is, you don’t dispute it, you accept. You have no right to speech. You don’t speak. You wait and wait. You ask for nothing.”

It’s 1939. You’re six years old. You were born in 1933. On January 30th that year, in Germany, President Paul von Hindenburg names the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party, Adolf Hitler, as chancellor. A countdown has started for another European disaster. Men will be soldiers, and war always returns. Camus again: “‘There has always been war,’ says a character, ‘you quickly get used to peace. So, we think it’s normal. No, war is what’s normal.’”

For those generations, war isn’t outlandish or on foreign soil. It adds to the family’s foundational stories. They’re the offspring of war, have been for generations, their lives shaped by conflict. It starts in 1870, with the Franco-Prussian War, which France lost. So, Stéphane grew up in a defeated country, stripped of the regions of Alsace and Lorraine that went on to belong to the German Empire. His was a generation obsessed with military revenge.

Others in the family remembered seeing the Prussians and held a grudge: “On my mother’s side, one day we saw some minuscule old ladies arrive, all in black with black bonnets. They were Franc-comptoises. Distant ancestors. I can see black silhouettes. One of them had a husband who was a sergeant in the army of Bourbaki (under Napoleon III).” From her you inherited a soldier’s wooden canteen with the name Godard carved at the bottom. “This was in the war of 1870. There was a General named Bourbaki that fought against the Prussians and took refuge in Switzerland. She said: ‘I saw the Prussians and dogs of their ilk.’ That’s all the way back in 1870.”

Revenge for that came in 1918 and Stéphane served in the army that exacted it, and though he keeps conspicuously silent on the facts, he flaunts his Military Medal and he’s always up for having a dig at the Germans. Uncle René also knows World War I by heart. Born in 1900, he grew on a military fault line, in the city of Sedan, in the Ardennes region, the site of a Prussian victory in 1870, of a German victory in 1914, the first battle of the Western front when French forces were forced to retreat. For four years, until being liberated by the American and French armies, his hometown was occupied by Germany. You remember your uncle telling you of the hunger, of stealing potatoes from the fields to eat.

For the family, the sworn enemy has always been the Germans, the Prussians, the boches, or whatever each generation called them. And in case you forgot about them grandpa brought it up every supper: “Another one the Fritz won’t have!” he’d say after finishing his food. “The boches were bad, but you’d just eaten. They’d taken Alsace and Lorraine, been a royal pain in the ass, but food is in our stomachs. This one they aren’t getting! They swallowed up Alsace and Lorraine but they’re not having my plate. It proved the fight kept on going, another one over them.” Now it’s started again, martial rumblings are coming from the eastern neighbor.

First, military conscription is reintroduced in Germany, in March 1935. It violates the terms of the Versailles Treaty, which had settled the crippling conditions of Germany’s defeat after World War I, and planted the seeds of future conflict. A year later, on March 7, 1936, Germany re-militarizes the Rhineland region, on the borders of Belgium and France. Again, treaties go unheeded and protests swell and fade. Two years later comes the annexation of Austria into Germany. The same year, Hitler nearly unleashes war by demanding to be given the Sudetenland, a part of Czechoslovakia. At the Munich Conference in 1938, with Italy, France, and Britain, he gets his wish. On September 30th, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain speaks of a “peace for our time.” On March 15th Hitler violates the Munich agreements and goes for the Czechoslovak state. The invasion of Poland sets off the war, in 1939. Britain and France declare war on Germany on September 3.

“The declaration of war, I remember. It was in the air. Planes had flown overhead. We didn’t know if they were Italian, if we would be bombed. We knew nothing. There were planes. Nothing had changed, except it was war.”

The months that follow are remembered through the distorting glass of wartime news. “In the newspapers there was talk of skirmishes. I recall small illustrated weeklies, you could see images, a German interior, on the table there were apples, with a portrait of Hitler above it, and you saw a French soldier that is about to throw one on his face and another stops him because it might be mined. I see it clearly.” It means to say that Hitler’s portrait itself is a menace, so treacherous are the enemies: “Germans mined everything, Achtung Minen, ‘Don’t throw it, we’re going to blow.’”

Wartime builds, and you’re consuming it. “These were popular illustrated weeklies, that fed people the idea that they themselves had of war.” It comforted and confirmed their idea of it. “We didn’t know anything about war. There were no reporters, no photos.”

There’s not much to see at first. War takes its time to actually begin. “War comes, it starts in 1939 and it lasts. Nothing happens.” Small-scale actions take place. Some British vessels are sunk, and a German district is invaded. There’s economic warfare. World War II doesn’t start with a bang. It’s the period referred to by the French as the Drôle de guerre, the “funny war.” It was called the “Phony War” in English, and Churchill coined the term “Twilight war.” Germans opt for “Sitting war.” It’s the calm before the storm. It lasts eight months.

On your end, during that strange prologue, one thing remains certain: France will prevail. It had “the first army in the world, the second largest colonial empire. Everything was in order, all was well.” It says so everywhere. “There were large posters: ‘We will vanquish because we are the strongest.’ You saw the map of the world, in red the English colonies, French colonies, the whole world, and ever so little: Germany. So, it was evident we would prevail.” Nothing to worry about. “There was the Maginot Line of defense, there was our army, there was General Gamelin!” What could Germany do before that might? “Illustrations in the newspapers showed the last parade of July 14th, 1939, a magnificent army, Spahi troops, Tabor troops, the colors and the empire.”

The funny war leaves colorful imagery I see in old newsreels and you recount to me, of French soldiers having wine, of French soldiers in train stations. Of roses being planted on the defense line to boost soldiers’ morale. The uniforms are still those of World War I. “In France we were continuing the war of 1914. A good war, proof was that we had won it.”

Newspapers of the time make for strange reading. On January 3, the newspaper Le Matin quotes Marshal Pétain, the French hero of World War I, then ambassador in Spain, as saying “we await without fear the great clash,” and that France “has all the required conditions for victory.” On the 6th of January, L’Intransigeant reports “Hitler is again considered as very ill.” His throat hurts, and it might be cancer.

In Marseille things continue unaltered. “We returned to school, I went back to the White Rabbit School, my grandfather led me by the hand. Life went on.” You went to Mass every Sunday morning, then Vespers. Church was good: it helped you discover Charlie Chaplin’s movies. “On Sunday, after Vespers, the priest took us to a room with a small projector and showed us that. Chaplin was everywhere at the time. I don’t remember what I saw, only Chaplin with his ridiculous pants, his large shoes, his vest, moustache and cane. I see him very clearly. Chaplin was general culture.” It was too early for you to see The Great Dictator, his parody of Hitler. By the time it made it to Europe, it couldn’t be shown in France.

Until the spring of 1940, there was nothing to worry about. France was safe behind its militarized border. There were fortifications meant to stop Germany’s advance “except they went from Switzerland and stopped at the Ardennes Mountains. Marshal Pétain had said ‘the Ardennes are impassable’ and if ever they try to cross them, we’ll catch at the exit. Catchy. So, from the Ardennes to the sea there was nothing (as defense). Sure, the Belgian border, but we know the Germans don’t violate borders…” On May 10th, 1940, German troops marched into Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxemburg. Italy joined Germany a month later. The “funny war” was over and the blitzkrieg, the “lightning war,” had begun.

The city of Sedan, Uncle René’s city, is once again the theater of defeat. On May 13th, the French front is pierced there, north of a Maginot Line rendered useless. Not that you’d expect it by reading the papers barely a day before.

On the 12th of May, L’Auto was categorical: “The Germans have not succeeded in their plan for lightning occupation,” and “resistance lines have not been pierced.” The German tactic “has completely failed.”

As the German army rushes to the English Channel to cut off British and French forces at Dunkirk, Prime Minister Paul Reynaud takes a bet on old glories to rescue a desperate situation: On May 18th he “names Marshal Pétain as vice-president of the Council. He believes he’ll reassure the French by calling to his side this icon of the Great War, despite his eighty-four years of age. It’s the beginning of a misunderstanding,” writes Henry Rousso, a French historian specializing in WWII France and the societal inheritance of the Vichy Regime: “the Vichy symptom.” Pétain is called upon to breathe new life into the fight. The opposite will hold true.

It’s all coming apart at astonishing speed, yet the good news remains. “I followed the war in the newspapers and the radio, which said only bullshit: Germans advanced but they were pushed back always with ‘heavy losses.’ Except they were advancing a full speed, ninety miles per day. Luckily, they had ‘heavy losses!’ What a joke.”

On May 23, three days before the battle of Dunkirk, Le Petit Parisien publishes a remarkable article: “The enormous losses of the invading army cause deep anguish in Germany.” It’s author, Lucien Bourgues, claims that the enemy press is telling “absolutely fantasist” tales of nearing victory. All lies, he writes. On the contrary, according to “certain sources” the German population’s morale is “seriously hit.” The German people are “absolutely distressed by the huge losses,” and in the cities of the Reich “word of mouth” is of 500,000 dead and injured on their side. “The unending sanitary convoys flowing from the combat zones are hard to hide.” That same day, in the same newspaper, French General Weygand is quoted as saying he is “full of confidence” as long as everyone “does his duty with a ferocious energy.”

By June, there are some eight million people fleeing southwards on the roads of France as the German army makes its way to Paris.

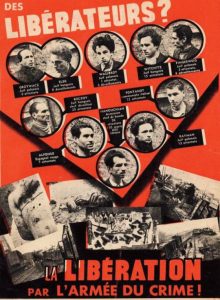

Escaping “in apocalyptic disorder” are the French from the north and east; the Parisians; the refugees from Belgium, Germany, Austria, and Poland, many of them Jewish. It’s all unwinding on the roadside: “French society seemed to come apart, and the roads were crowded with millions of people. Walking south, or going south on bicycles, or old cars with mattresses and furniture tied to the roof, because it was the exodus as well as the defeat. The exodus seemed to show the society, the state had ceased to exist,” Robert Paxton, Columbia University professor emeritus, specializing in France’s Vichy regime, tells me. It’s the image of a country disintegrating.

The government flees Paris for Bordeaux. On June 16th, Paul Reynaud resigns. Marshal Pétain, the aging talisman, is called upon to form the last government of the French Third Republic.

Once upon a loss or another, are all the various beginnings for this story. Start with a speech on the radio announcing defeat; start on June 17th, 1940. That radio broadcast and Pétain’s voice. You remember it, seventy-seven years on, and to you, defeat is an old man’s tears.

“I saw my grandfather cry, I listened. It was 1940, I was seven; I notice that my grandfather is crying, that the country is lost. My grandfather, when he heard ‘it is with a heavy heart that I say to you today that the fighting must cease,’ my grandfather, who had fought in World War I, cried.

It was supposed to be the first army in the world. He had spent his life in the army, and the Marshal tells him… ‘the fighting must cease.’ In 1914 the fight went on. There was the German offensive, there was the battle of the Marne, there were the trenches, and then guys, generation after generation, falling, dying, returning mutilated, but the fight went on. And here in mere days everything’s done and dusted. There are no words.”

Why is this man crying in his old age as France comes undone? They must have been countless like him, crying, at the news of France’s capitulation to Germany. But a man, all the while crying in unison with the many, also cries alone. Stéphane Godard cries for his life. He cries because it’s Germany, who had defeated France in 1870 and taken the territories of Alsace and Lorraine, because he grew up wanting the revanche and got it in World War I. He cries because he’s a soldier and he won that war and nothing will ever come close to that achievement. He cries because this feud has presided over much of his life, and after each meal. He doesn’t say Germans, he says boches, a contemptuous word, from his world, of which the Marshal is the uncontested idol, the victor of the battle of Verdun, the man who stopped the enemy tide. He cries because it’s Pétain talking, it’s Pétain admitting defeat, and though he’s then a national treasure, he’s also a mirror in which Stéphane can intimately fathom the disaster. Stéphane is a man of the nineteenth century, like Pétain, a man of rural origins, like Pétain, from which both went on to spend a lifetime in the military. He cries because once upon a war, he won the Military Medal, and Pétain wore it, too. It’s the hero of his generation. It is a narrative that gave him meaning. All dissolving in tears on a day in June: the fall of France.

PART II: THE MARSHAL

“No one who lived through the French debacle of May-June 1940 ever quite got over the shock. For Frenchmen, confident in a special role in the world, the six weeks’ defeat by German armies was a shattering trauma.” —Robert Paxton, Vichy France.

That Monday the 17th of June 1940, at 12:30 in the afternoon, “the world explodes, all things fall apart.” The radio is on at home and the broadcast, playing out on the distraught face of your grandfather, carves itself into your memory. The implications overwhelm you, rendered by tears you cannot forget—the symbol of an ending.

The rest is blurred. The radio could be in the living room or placed on the terrace outside. Mother is probably at work, grandma and your brother out of sight, maybe your little sister on the fringes, unaware, playing. You’re alone with an inconsolable adult. “I was a little Frenchman and my country has completely crumbled,” along with the man who had served as your father. There is still the vestige of shock when you speak about it. “There was no army, nothing. Tomorrow the Germans could arrive.”

To you that’s how it all begins, this story about that boy you were; the boy you can’t save.

First, though, in that moment when all seems lost, something remarkable happens. Providence issues from the airwaves: “I give to France the gift of my person in order to alleviate her suffering,” you hear Pétain say. It’s the voice that will shape your childhood and echo throughout the years to come.

For with this Christ-like phrase, a new faith is being born to you.

“There was chaos.” Then there was him. “It was the divine voice!” When every certainty seems void, Pétain steps forth to fill the vacuum. Amid the ruins of humiliation there is a reprieve. “There’s nothing, nothing, nothing, and you feel betrayed, cheated. You’ve fallen into the bottom of a hole, and there’s one ladder to get yourself out of it: there’s the Marshal.”

For you this moment breaks the dam of everyday words and you turn to the only imagery that could match it. “France was lost” and “the Marshal was Joan of Arc,” “France had drowned” and “he was Moses.” Reliving the trauma of those days is done in the halfway house of biblical allegory and historical alchemy. The child of a religious and military family hears the voice of its greatest icon and wants to believe in a miracle.

“He might have walked on water; with the Marshal everything was possible.” If not him then who? “The victor of Verdun! Verdun was when we stopped the Germans. They needed to be stopped and he did it.” Pétain’s myth grows ever larger in light of unparalleled disaster. Beyond these walls, in the north of the country, of the Loire River, millions are flooding the roads before the cataclysm engulfing proud France. Could he rescue you again? “France was on the floor and the one thing left standing was him.” This, the country’s vulnerability mirrors your own. “I remember being poor and weak, that anything could happen and that it wouldn’t be grandpa or grandma, or my mother that would protect me, I was completely defenseless and hoped to be spared by my insignificance.” The nation’s salvation feels all the more personal.

As the first step out of the pit, Pétain announces he’s asked your adversaries “to put an end to hostilities.” It’s happening “honorably.” You expect his next speech to know just how the world will go on turning again. “We waited, there was this war that the Germans had won, but then they never showed up. We waited. My grandmother prayed. The elderly didn’t understand. They had their time, they had had kids, they were happy, they had had a job, and suddenly it was over.”

Your new reality starts to take shape on the 25th as Pétain announces he’s signed an “acceptable armistice” with Nazi Germany days before, calling upon their “sense of honor and reason.” There will be no more fighting. He assures you “love for the nation has never had more fervor.” It will need to. The conditions imposed are “severe.” He won’t lie: “You’ve suffered. You’ll suffer still.”

Take a map of France and slice off the north, including Paris, then all the western coast on the Atlantic all the way down to Spain. That’s how country will be divided, what the Germans will occupy. That’s three-fifths of the country under German rule. The French army will be demobilized. The 25th of June is declared a day of national mourning.

What’s left is an exception, a unique case among all the countries conquered by the Reich. It’s the only one accorded an armistice, to retain a semi-independent government. Now there’s an “occupied zone” in Germany’s hands and what remains is the southern “free zone” split off from the rest. That’s where you live, what remains sovereign under the guidance of Pétain. As Hitler wished, it both avoids the victors the administration of the whole country while imposing his severe economic and material demands on the defeated. Amid the various clauses, you’ll learn one day, there’s betrayal of French sanctuary, the handing over to Hitler of the Austrian and German refugees. That’s the deal struck to preserve a semblance of French rule. For you it symbolizes hope. “The Germans left a piece of France unoccupied. It was nothing. But it was the free zone.” It’s from this amputated homeland you’ll mold your understanding of the world, the shape for the future. “From there came the attempt to reorganize a state, an army, but above all to remake France.”

That is what you’ll retain from those foundational times. France needs deep surgery. It needs explanations and solutions for that calamitous defeat and its consequences. And Pétain provides them: “The failure surprised you. Remembering 1914 and 1918, you seek for its reasons. I will tell them to you.”

What he spells out is a tale of guilt and redemption. It wasn’t the military’s fault, he explains, the disease runs deep into politics and society. Because of his narrative of decadence, the actual aftermath is all too clear for the little believer.

Why are these trials upon us? We’re being punished. “Since victory, the spirit of pleasure has overtaken the spirit of sacrifice.” You listen, learn and repeat: “Sacrifices will need to be made, the Marshal said. Which meant you enjoyed yourselves, and now you’ll pay for it. At Verdun they had sacrificed.”

Yet afterwards “France had lost its soul, lost the taste for work, and on top of it, aperitifs, dancing, had lost the healthy values of work and sacrifice.”

Instead “of continuing to serve and give it all to France, you had thought only of vacations and pleasure.” It’s a lesson you can understand. “The boy’s been naughty, now’s his punishment. Morally, France has sinned, it had been punished and now it needed to be lifted, thanks to daddy Pétain.”

For Pétain says there’s a way to redemption still. For that boy, in memory, all that the Marshal announces is enshrined into righteous fact. “I believed that one day France would be strong again and one day we’d be winners again, that maybe…meanwhile there was Pétain.” The dogma transfigures your understanding of this period.

And though the adult knows better, those memories belong to a boy caught in an instant when history changed course and he was swept along. “It’s hard to convey those speeches now. You can’t judge a time without living it. Reading it afterwards is done with a cool head.” And though a lifetime has passed, it doesn’t sever the bond to an expired truth that you can still reach for, like a phantom limb. That pillar that sustained this dream of salvation on the brink: “You’re a kid. There’s the Marshal. You must be well behaved. You must be good. And later, maybe, we’ll have an army again. Maybe we’ll be great again.”

As historian Henri Amouroux, who served in the French resistance and specialized in German occupation of France, writes, “in a defeated country, in search of extraordinary men to offer to the admiration of the crowd, there remains only one extraordinary man: Phillipe Pétain.” Peace and a return to a semblance of normality is what most people desperately desire and rejoice in seeing it within reach, “For there is no mistaking the joy and relief flooding after the anguish,” Paxton writes.

There are voices that arise against this narrative. An opposition to Pétain had arisen, though dimly still. On the 18th, in a broadcast issuing from London, General De Gaulle has rejected the surrender and rallies France in an opposite direction: “France has lost a battle, but France has not lost the war.” He envisions that the conflict will be long and its outcome still uncertain. You do not hear his call. In the face of the neutrality of Russia and the United States, his vision then still seems a folly. “The people who believed in 1940 that Hitler would be defeated were visionaries, like De Gaulle, they were believers, there wasn’t much concrete to defend such a belief,” Paxton tells me. For you, then, there seemed no possible alternative. “Do you need me to draw you a picture? There were no Americans. The Russians helped the Germans. Stalin and Hitler were having their little love-in. Now they would turn to conquering the world,” you say. “It was over. The old civilization had crumbled. What do you hang on to? There was the voice of the Marshal.”

Had your family heard De Gaulle’s call it would not made much of a difference. There could be no competition with Pétain. “My grandfather and my mother were fully behind the Marshal. Everyone was.” His most fervent supporters were veterans, men such as your grandfather, men shaped by the Great War such as your Uncle René. He stands for all they believe in. “A family of the military, I’m a little French boy, a Catholic, it’s the basis, it’s everything. Everything we were stemmed from this war in which we had survived thanks to daddy Pétain. It’s the family’s way, the prism through which to peer into their view of the country’s fortunes.

At this point they are among millions; their fervor, despair, and allegiance reflect the vast majority of the country. As Henry Rousso writes: “This adherence often takes the form of devotion, of a religious mystique that ties the personal destiny of individuals and the collective destiny of the nation to the word, when not the actions, of a providential man.”

Voices from all sides explain the aura that then surrounds Marshal Pétain. Time and time again he embodies salvation. Writer Ernst Jünger, then an officer in the German army, remembers seeing columns of French prisoners “who dragged themselves through the road’s dust, in the torrid July heat, and acclaimed his name as that of a savior.” From another standpoint, Walter Stucki, then Swiss ambassador to France, wrote in his memoirs, “In July 1940, the new head of the French state had behind him not only an important majority of the National Assembly, but also the greater part of the French people. With an almost mystical veneration he was treated like the savior of the nation.”

“He stops the war and France must be remade and there’s only him,” you tell me.

All he needs now is the power to carry out it out.

Cometh the hour, cometh the savior.

Democracy dies swiftly and by an overwhelming margin.

It happens in the small city of Vichy, near the border of the newly divided state, where the government will reside after its flight across France and with Paris occupied.

On the 10th, in a vote of 569 votes to 80, both chambers give Pétain the authority to make a new constitution. You tell me “he was Moses, he could speak, he could dictate the Tablets of the Law.” Now he indeed can and does. By the next day, three constitutional acts place within his hands alone the executive, judicial, and legislative powers. He takes on the title of Chief of State and suspends the assemblies. The Republic is dead. Less than one month after defeat, Pétain has established the basis of a personal dictatorship. Welcome to Vichy France.